The psychology behind the rise of WhatsApp

The main reason why Facebook bought out WhatsApp for a whopping $19 billion is that young people are now using instant messaging apps more than social networks. That's easy enough to understand, because it is the age of the mobile phone. But there is something more fundamental at play here, and that has to do with what we share and with whom.

Recently Facebook released a paper on user behaviour. Two researchers collected data for 17 days on what they called “self-censorship”. They found that seven times out of ten, somebody would enter text into a status update or comment box – and then not post it. In other words, we have become so conscious of what we post on Facebook that we often think twice.

How comfortable are we on a public platform?

What began as a network of friends and family has grown into a public platform. With people close to us, we can share a family picture or a politically incorrect wisecrack without hesitation. That's not so any more on Facebook, even within well-defined groups. A recent study published in the journal Cyberpsychology pointed out that the more friends a student had on Facebook, the less likely he or she was to talk about gay rights, for example.

The journal's editor, Dr John M Grohol, concludes that when our friends circle widens beyond a certain point, identity management becomes the primary focus on a social network, which in turn becomes an increasingly impersonal platform. Facebook pages were intended to separate the personal from the more professional uses people and companies make of the social network – but the lines have got blurred. How we are perceived by 'friends' has become a primary concern when we post anything, anywhere on Facebook. This makes it a great platform for building one's identity or brand, but not so great for sharing our innermost thoughts or intimate pictures.

How much do we value our personal spaces?

Instant messaging apps like WhatsApp – as well as Hike in India, WeChat in China, or Line in Japan – thus address a deeply felt need that Facebook can no longer fulfill. Even though Facebook also has a messaging feature, it's far simpler and less obtrusive to use a phone messaging app. So even though the meteoric rise of WhatsApp is related to the growing ubiquity of phone usage, the nature of the platform and our personal comfort level have a lot to do with it as well. Sending a picture to a set of friends on our phone address book is very different from posting it on Facebook. The frame of mind in which we chat on a messaging app is much more relaxed than on a social network where we are more and more on our guard. At the same time, when we want to broadcast a thought or article or photo to a wider audience, we will probably do it on Facebook or Twitter.

In that sense, the acquisition of WhatsApp by Facebook would seem like the perfect symbiosis, where you get the best of both worlds from the same provider. WhatsApp becomes an extension of Facebook and vice versa. But there's a catch. The more impersonal Facebook becomes as a medium of communication, the less engaging it is for us. We may start spending less time on it, in which case the number of active users on it may decline, and then it gradually loses its mojo as a branding or identity platform. Can Facebook stave off its decline by integrating WhatsApp and other apps to make itself useful to everyone? That depends on what you, the user, really wants, deep down.

Let us know in the comments below.

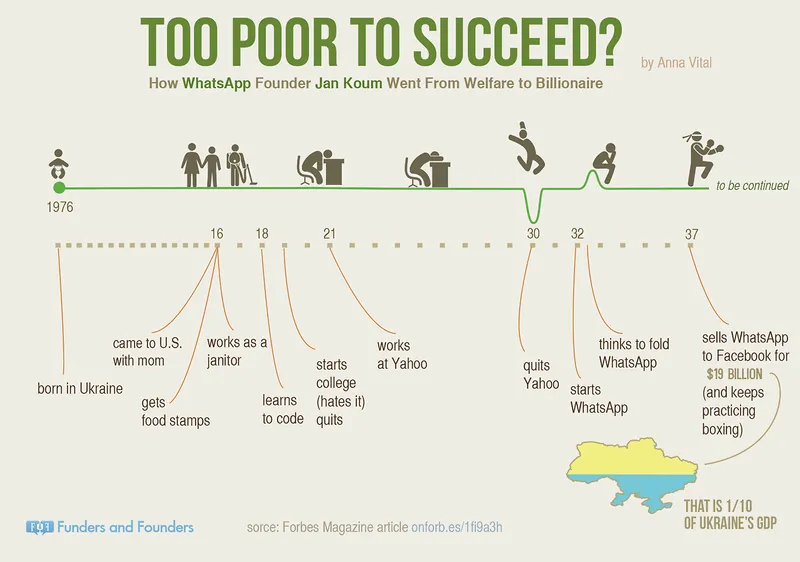

Check out this infographic form Funders and Founders on " How the Whatsapp Founder went from Welfare to being a Billionaire "

![[Funding alert] Workflow automation app Delightree raises $3M in seed round](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/b3bfb136ab5e11e88691f70342131e20/Delightree-1596266034279.jpg)