Journeys with Meaning- Inside and out

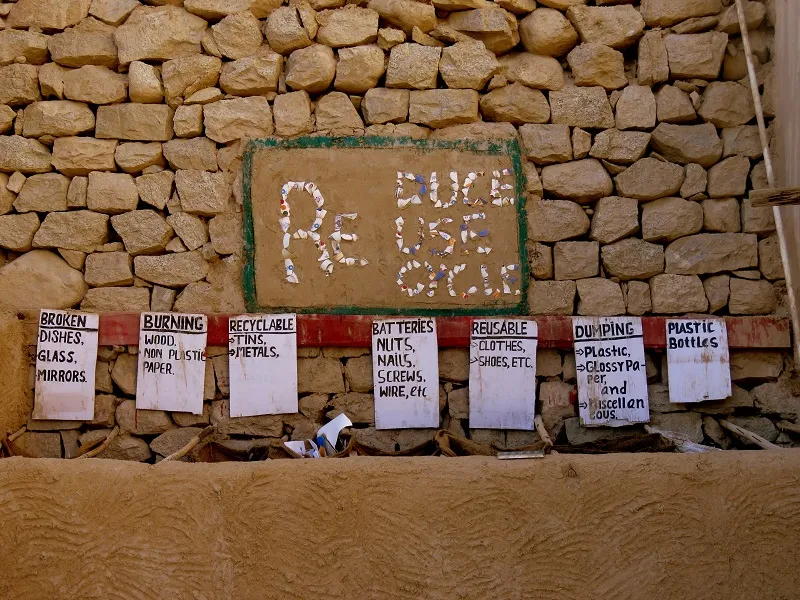

We were clearing away the little trash we had accumulated at the camp where we spent the night. To burn, bury, or carry along were decisions to be made. Small bits of paper were chucked into the little fire we had going for tea. Someone wondered aloud, “Maybe we should carry these bits of plastic back to the village and put them in a bin.” Our local host didn’t skip a beat in saying, “Maybe the fact that the piece of plastic came to one of us is itself the problem. Whether we burn it, take it back to the city or trash it in the village is only a matter of transferring guilt.” This was an interaction in a trip I recently went on, with a group called Journeys with Meaning (JwM). Vinod Sreedhar leads JwM.

Fifteen years ago, Vinod was composing music and was part of the advertising industry. He found the creative processes exciting but was disillusioned by how the industry operated. Conservation, ecology and citizenship were issues Vinod felt strongly about, and he quit advertising to pursue these strains.

Along with a group of friends Vinod started working with young people on these issues through classroom sessions and workshops. After a few years and a lot of thinking, Vinod realised that the workshops weren’t creating the kind of impact he would have liked to see. “Disconnect is a key challenge,” says Vinod about his experiences of these workshops. He observes four kinds of disconnect that most people in our times face. A disconnect between - humans and nature, different cultures, the head and heart and between actions and consequences. JwM, through its trips, hopes to be a step towards reducing these gaps.

Having travelled extensively himself, it was his experience at a conference in Ladakh that set Vinod thinking of the potential travel holds for reinitiating connect and thinking around conservation. Could the barriers faced in discussing these issues in classroom sessions and workshops be overcome through travel? What if discussions on conservation are taken out of workshops and are woven into an experience, or a journey?

JwM curates visits and interactions in places that are rich ecologically, and with people who know these places intimately. The Assam-Meghalaya trip that I was part of has walks and hikes, moving around in a sacred forest and root bridges, camping and safaris in Kaziranga. Seamlessly woven into these are film screenings, discussions with traditional leaders of the Khasi community and organisations working in the region.

We had just about recovered from a five-hour hike, when we set out once again for a much shorter one, to a living root bridge. In some parts of Meghalaya, people have worked with trees on either side of rivers and streams to shape and nurture roots to form living, growing, breathing bridges. Bone tired and weary, one can only gawk and marvel when we get there. Written words, descriptions or photographs don’t have the potential to move you the way standing on it after hours of hiking does. We’d travelled some distance to experience this and every laboured breath was worth it. An easier option would be to visit the better known Cherrapunjee. I’m told it is bustling with tourists, music and vehicles. It’s apparent why the ‘easier’ option was not exercised.

Vinod shares, “We encourage people not to tag [on social media] or give away the name and location of the village or the bridge.” As the trip progresses I understand this comes not from the desire for exclusive access, but to respect the desires of those working towards building responsible tourism in the area. People in the village around this bridge know of high tourist footfalls in the popular spots. While some hope that increased numbers here too will help, others wonder at what cost this will be. The discretion required by the group in talking about the spot is an effort to let communities take time to figure out how they’d like to engage with travellers, before they are left with little choice in the matter.

James, our host during the trip, tells us about Mawlynnong, a village in Meghalaya. Some years ago it was touted as the cleanest village in Asia. How someone arrived at this assessment is a different story. But almost overnight it received attention from different quarters of the media and, subsequently, swarms of tourists descended on the village. Were the people of Mawlynnong prepared for this? What kind of the impact did this kind of tourism have on communities? James observes that during popular holidays and weekends there is a long trail of cars and fumes right outside the village. Often, tourists visiting the State keep Shillong as base and drive to Mawlynnong, eat packaged food, look around the village and drive back to Shillong. Many don’t even stop for a meal or a conversation. So why visit the ‘cleanest’ village?

James shares questions he feels are fundamental when we view tourism and local communities- What is the kind of tourism people desire around their homes and villages? Are they at the negotiating table when some of the tourism promotion decisions are made?

These are communities making their way through a context that is rapidly changing, and James’s homestay, Maple Pine Farms, and the smaller homestays he engages with are answering these questions for themselves. They are hosts to JwM’s travel groups and for many these conversations have impacted how they view their own travel.

About a year and half ago, Namrata went on a road trip to Ladakh with a group long known to her. She learnt how to ride a bike for this trip and rode through major parts of the landscape. At one point, the group was sitting at Pangong lake when a co-traveller played some music loudly and a group gathered around to dance to it. She says, “I asked myself, ‘Is this what I came all the way to Ladakh for?’”The incident she shares was possibly one of the few that increased her discomfort with the place and the experience.

Six months later she travelled with JwM to Meghalaya and it helped her realise why her trip to Ladakh had felt so wrong. “We focussed on getting from one place to another,” she laughs and shares. “I didn’t have any conversations with locals, nor did I learn anything about the place.” After travelling to Meghalaya with JwM she decided to experience Ladakh with them.

Four months after her second trip to Ladakh, her joy is still contagious. She was warmed by the people she met, inspired by the lives around and felt connected to events and places in a way she hasn’t before. She felt humbled during her interactions at SECMOL (The Students Educational and Cultural Movement of Ladakh). More so when students showed her a home they built using a Jeep that was to be scrapped. “Since I got back, I’ve been following and reading up about Sonam Wangchuk’s work and SECMOL. Our regular news fixes don’t cover such inspiring stories, so I’ve been looking up other news platforms, reading whatever I can find.” She plans to volunteer at SECMOL soon. She speaks of how homestay hosts and co-travellers who participated in the Ladakh Marathon have been an inspiration. She has been training and has completed two 10km runs and is training for the third as I write this.

What is the ‘Meaning’ part of JwM? Vinod, Neha and Homi who form the JwM team see this as an opportunity for groups to look closely at a place, its people, conservation and ecology. These are experiences that put into focus the world around and importantly inside of us. Vinod also conducts workshops, called Inside Out, to help people look inside, identify aspirations and ways to work towards them. On the surface one might see JwM and Inside Out as dealing with different realms- the outer world and the one within. Srinath Perur in his book If It’s Monday, It Must be Madurai writes about Vinod, JwM and Inside Out “It’s evident during the Assam Meghalaya tour that he feels that these are connected: It’s the same system of thinking – or unthinking – that creates ecological imbalances as well as causes people in cities to be stuck in unfulfilling jobs.”

While travelling with JwM I took away a stronger belief in facilitation of a certain kind. The kind that is gentle and based on questions, experiences and conversations. It nudged me into listening to myself more clearly. Namrata is still high on the warmth she found in Ladakh and is inspired by people she met on the trip. She finds herself having conversations about responsible and meaningful travel with other groups she travels with. She is tuning into efforts like SECMOL. She is running.

This article finds a place with SlowTech for the processes JwM follows and the ethos it stands for. Connect with them throught their Facebook page or send them an email at [email protected]. If you have such stories and want to contribute, write in to us at [email protected].