Aibono conducts farming in the cloud, increases yield on the ground

The $300-billion-dollar agri industry in India is in need of alternative technology, one that could measure soil and cropping patterns, to change lives of the farmer.

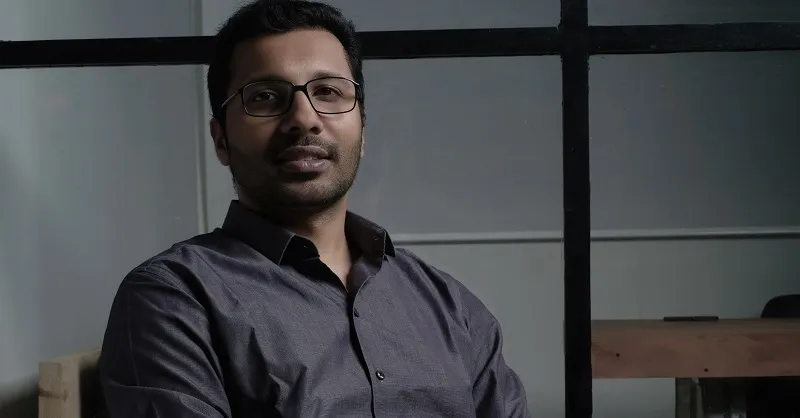

Deep in the mountains of the Nilgiris, Vivek Rajkumar, a 29-year-old engineer, is hard at work with 150 farmers. Each day he visits 20 farms to check on his 'collective', a 300-acre farmland that Aibono, Vivek’s company, has aggregated with technology, and uses data from the earth to deliver better yields to the farmer.

Back in his 700sqft office in Bengaluru, he is constantly looking at data feeds coming from the farm, the same data that has helped change lives of the farmer. Wiping his glasses, he tell us, “I had to prove myself to those 150 farmers before they began using the technology that my team has built.”

Aibono was born out of personal trials, and it is not often that one follows the stories narrated during one's childhood. Vivek was told that his grandfather was a very popular farmer in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala. His legacy remained with the young Vivek until he finished his stint at IIT Madras, where he befriended several people who were into building social enterprises as well.

After his graduation in 2011, he convinced his parents that his future was in farming. They loaned him some seed money and the idea of becoming a farmer finally took root.

With the help of a local he began farming on one acre of land. He invested Rs 1 lakh into growing rice and spent the money on fertilisers to ensure a good crop. The crop did not yield optimal results and Vivek’s investment was under threat because the yield did not fetch a profit in the market.

But the 125 days of hard work was not wasted on Vivek; he recorded everything from the type of seed used, and the amount of water and fertilizer infused into the field.

He tried again, in the second year, and he realised that the yield had slightly improved, but not enough to make him money. But he had the data to understand how the land works. He wondered at that moment, in 2013, if he could build a platform that could capture all the parameters of operating a farm and make sense of it.

He added a couple of important parameters, like weather and soil condition into the mix, and then magic happened in the form of Aibono.

The business

In 2014, when Vivek took this idea of making farming successful with data to IIT Madras, the faculty welcomed the idea. Vivek began to hire people to create data sets that could improve farming, and quickly reached out to tea plantations in the Nilgiris and some farms just outside Chennai.

He offered testing and measurement services to farms where a device would capture the soil and weather condition and also build in imagery of the region. The imagery or infra-red tells you of the crop stress. The platform also advised the farmer about the right fertilizer mix to be used based on the soil condition.

But in under a year he realised that the platform he was building would not be suitable for long gestation crops like tea, rice and wheat. Since he was in the Nilgiris to meet the tea plantations, he met cash crop farmers, those who grew vegetables, and told them about this concept of using data to improve their yield.

In sixty days, Vivek proved to them his offering and they came on board. “The yield was 30 percent better compared to theirs,” says Vivek.

The crops grown in the Nilgiris range from carrots, cabbage, cauliflower, to peas, potato and beetroot, and Vivek’s farming methods gathered the attention of 30 farmers.

Since 2014 the company has helped farmers with 350 harvests in five villages. The company has kicked in revenues as it takes a percentage for the yield only. It’s a service that the farmer pays for.

The technology is nothing but a device that collects data, which is then taken by a farm associate or the agronomist and sent over the internet—from the farm—to Bengaluru for data crunching. The farm is monitored daily and inputs are given to the crop based on the suggestion of the platform.

The farmer signs up with Aibono to receive consulting and data; the investment and the market risk is borne by the farmer. Vivek does not share a lot of data about his company because he says the technology is proprietary.

“We are a growing company and have figured out a model that makes farming a viable business,” he says.

Vivek plans to expand the business across the country and sources say that he has raised $500,000 from several investors.

Competition

Vivek has competition in some allied businesses like PEAT, Earth Food and V Drone Agro, which use imaging technologies and soil testing over the cloud to help farmers. CroFarm from Delhi, which was the number one company at TechSparks 2016, makes farmers discover better markets and pricing.

VDrone Agro plans to go live with several farmers by next year by working with government and semi-government agencies. “We need the data to prove that our research model makes sense for stakeholders,” says Kunal.

PEAT is a product company and is acquiring users at the moment. It is yet to generate any revenue. The app identifies plant damages just by taking a picture, thus aiding farmers to save their crop without losing much time. “To train these self-learning algorithms, a huge database is needed. Today, our database contains over 270,000 labelled pictures and it grows every day with every picture users send to us,” says Charlotte Schumann, Co-founder, PEAT.

PEAT has also closed a large round of funding and is working with ICRISAT to gather data on farming.

Aibono has nothing but a bright future ahead, because India has 600 million farmers and each of them has less than five guntha of land. The financial disparities in farming are higher than for those working in urban regions and this is because the farmer was only a vote bank and data was never considered important to change their lives. The future is in data and Aibono is showing the way forward.