Parched lips, barren lands and the scramble for water in Maharashtra

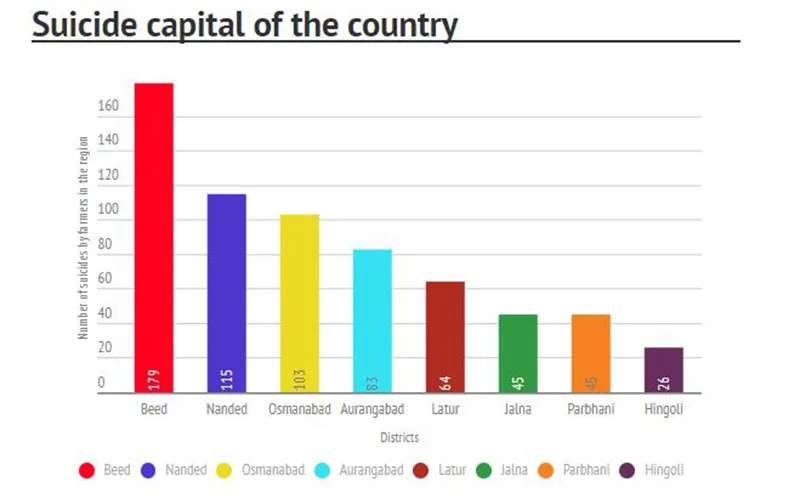

What are the factors that have caused the Marathwada region to be known as the 'suicide capital for farmers'? More importantly, do farmers here have some respite before the monsoon disappears?

From driving tractors, to driving cars — Laxman has come a long way from being a farmer in Beed, Maharashtra to now driving cars in Pune. "We always have a problem with water. However, this year is even worse in our area, but especially in Latur. People are not even getting water for drinking and bathing. Forget about water for crops. All our crops have been destroyed in the area. How will we survive? No wonder farmers are killing themselves. It is impossible to repay loans. What will they do? Not all are lucky to be able to find a job in the city like me," he says.

And right he is, for water is more precious than gold right now in the drought-stricken Marathwada region — so precious that it's even being stolen! Talking about stealing, Latur, which has shown the highest rainfall deficit this year, is also dealing with a booming water business thanks to borewells, private wells and tanker owners who have found an easy way to profit out of another's loss.

As much as 80 to 84 percent of the agriculture in Maharashtra is rainfed, but there is a huge variability in rainfall in different regions of the state. Deficient rainfall is reported once every five years and drought conditions occur once every eight to nine years, so droughts aren't unusual in the state.

Image: wikicommons

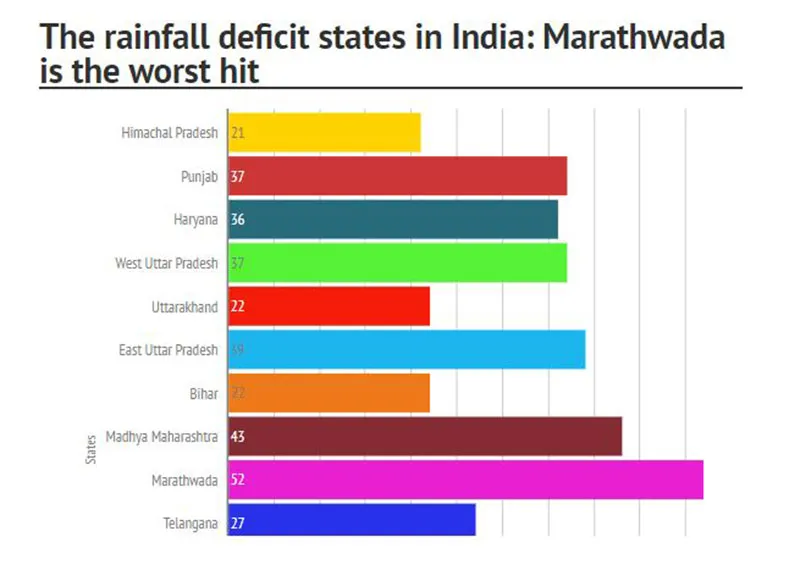

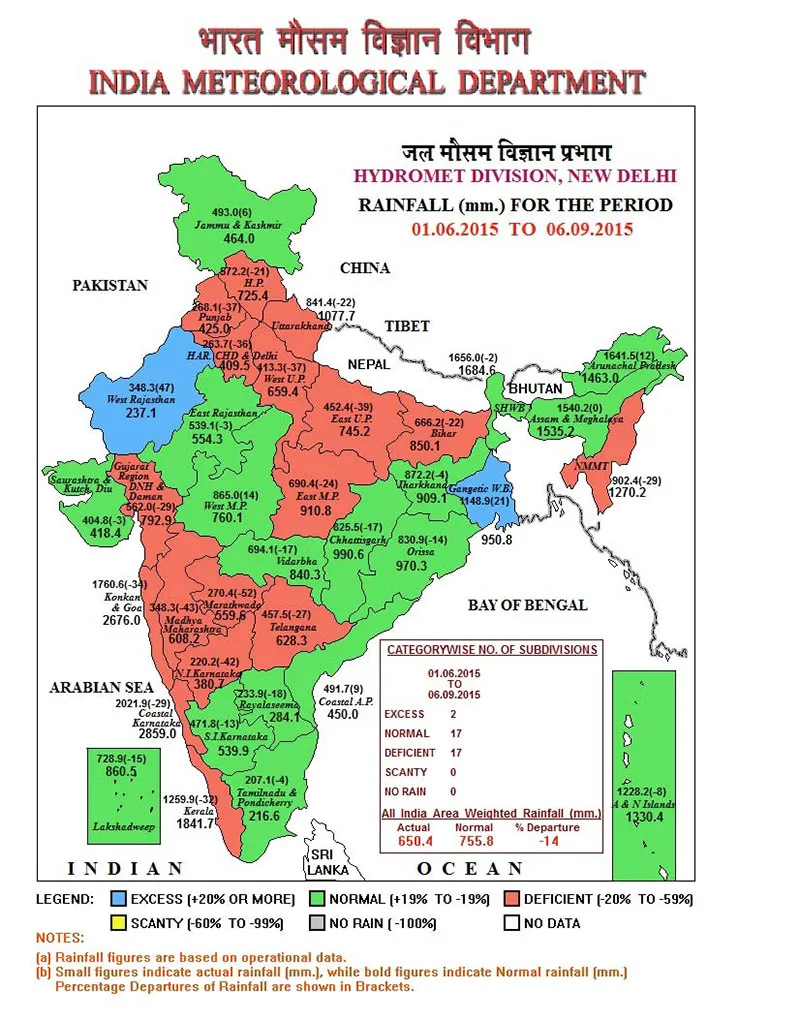

This year is different by all standards because despite being right in the middle of the monsoons, there is a huge deficit in rainfall, with 17 of the 36 metereological subdivisions of the country experiencing deficient rainfall.

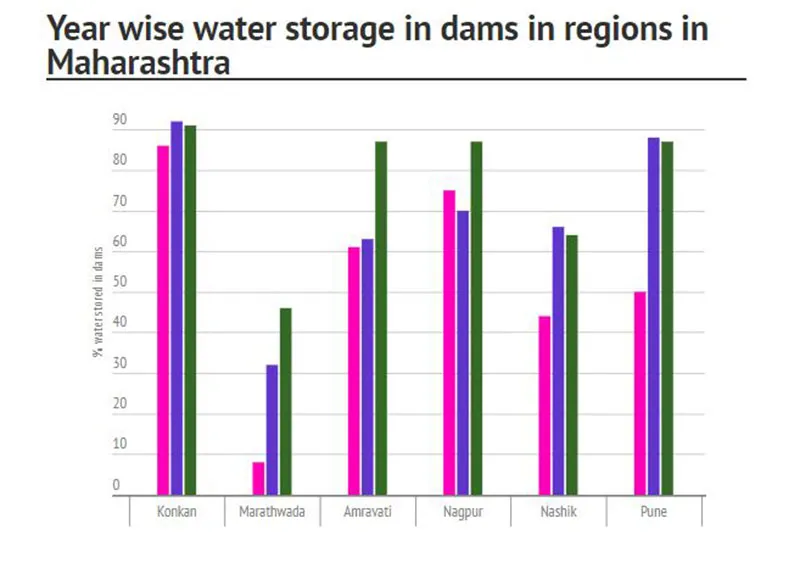

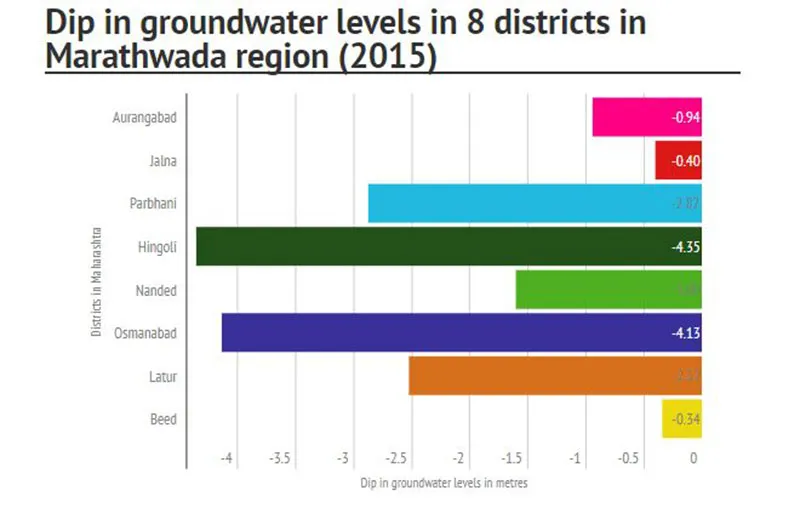

The state has only 49 percent of water storage in its dams and the water levels Marathwada's dams are precariously low at eight percent, raising fears of mass migration of people to Pune and Mumbai. The more alarming news is the continuing dip in water tables over the last five years. Groundwater Surveys and Development Agency (GSDA), 2015 data shows that the highest decline in groundwater levels this year appears to be in Hingoli district. The other district with a serious dip in water levels is Osmanabad, where the average water level this January was 6.87 metres, down from the five-year average of 2.74 metres.

Image: wikicommons

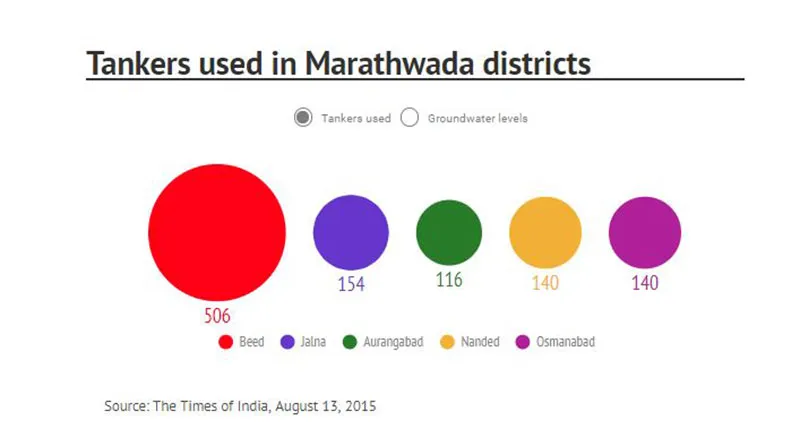

Reports show that as many as 10,000 borewells per month are being dug. Withdrawal has exceeded recharge to such an extent that aquifers have literally gone dry in many villages here. The density of borewells is as high as 210 deep borewells in a 40-50 square kilometre area in villages near Tasgaon. As many as 1,188 water tankers of 1,751 in the state are being used in Marathwada alone.

The impact of the drought on agriculture and the state of farmers has assumed alarming proportions, with as high as 630 reports of farmer suicides in the region giving it the dubious distinction of being the suicide capital of the country for farmers. The reasons are crop failure and increase in debt.

Image: wikicommons

As high as 70 percent of the farmland in Marathwada has registered a failed kharif crop this year. Four districts in the state — Beed, Latur, Osmanabad and Parbhani — have been put under the 'alert' category by the Mahalanobis National Crop Forecast Centre (MNCFC). Livestock too has become a burden due to fodder and water needs. Farmers are in a fix as they cannot even sell their animals due to the beef ban in the state.

The three worst affected districts of Beed, Osmanabad and Latur do not even have fodder to sustain about 22 lakh animals both big and small. Fodder camps planned by the government have not yet started due to administrative difficulties. Cow shelters are also unable to bear the load of additional cattle, thus forcing farmers to sell off their livestock at throw away prices. The crisis has resulted in reports of increasing unrest among farmers in the state.

Solapur and Marathwada are at loggerheads regarding the sharing of water from the Ujani dam. The government has been planning to supply water from the Ujani dam to villages in Latur by train, a plan that has been ferociously opposed by Solapur with threats of an agitation for taking Solapur water to Marathwada.

Image: wikicommons

Why has this situation come about?

The politics and economics of water use in the region that favours industries such as sugar, steel and beer, which need huge quantities of water, and the lack of foresight and mismanagement of resources has an important part to play in creating this situation.

Suneel Joshi from Jalabiradari argues that it also has to do with the narrow understanding of droughts as merely connected to a lack of rains. He argues that droughts are a broader phenomenon that have their roots in the breakdown of the indigenous systems of farming that have changed farming from a self supporting, interdependent and collective activity to a centralised top-down system that has increased the tendency of farmers to depend on the government.

Current water-intensive farming practices have increased the dependence of farmers on fertilisers and pesticides forcing them into a spiral of increasing debts while current policies have left him with no identity and security to deal with the situation.

Image: wikicommons

What is being done to deal with the crisis

Other than short-term measures such as providing relief packages to farmers in distress, creating jobs, discussing healthcare for farmers in depression, and understanding the lack of adequate water storage, no long-term plans seem to be in place to deal with the situation. Noticing this, even the Bombay High Court has come up with a suggestion to the government to come up with a disaster management plan to deal with the situation.

Experts argue that urgent steps need to be undertaken not only to limit sugarcane in the region — a step that is already being contemplated and awaiting decision — but to also encourage growing traditional crops such as pulses and oilseeds even if that might not get political support in the long run.

"We need a total change in perspective," says Joshi. There is a need to follow river basin approach and design for deciding a crop pattern in an area that would help in planning crops based on local conditions and availability of water. The government must also change its policies about crop prices and land prices to make them more advantageous and to improve security for farmers,"

Experts argue that a long-term plan for drought mitigation that focuses on overall development and includes soil quality, crop management, water management, alternative livelihood opportunities for the affected and livestock management is very important.

Image: wikicommons

Rainwater harvesting and other positive examples to learn from

All is not gloom and doom though. Maharashtra has been one of the most progressive states in terms of watershed development and participatory water management initiatives and has a number of success stories in the water sector, like that of Ralegan Siddhi, Hiware Bazaar, Soppecom’s work on water users associations in Waghad and Palkhed, work of Paani Panchayat, Afarm in addition to a number of centrally and state funded watershed programmes.

Some recent examples also come from villages like Khamgaon Maval, Manyali village in Yavatmal district in Maharashtra, Jalna district in Marathwada, Valni village in Nagpur, Naigaon village, Jamkhed in Ahmednagar district, Pingori village in Purandar taluka of Pune district, and Medsinga village in Taluka, Osmanabad. They have been successful in tackling their water needs even in the middle of droughts through concerted collective efforts at harvesting rainwater. These examples can serve as an inspiration for hundreds of villages reeling under drought this year. The recently launched Jalayukta Shivar Yojana by the government to deal with the drought situation in the state is also a positive step in this direction.

Image: wikicommons

The newspapers today have been full of reports of rain showers in thirsty parts of Marathwada and elsewhere in Maharashtra raising hopes that they might help to raise the water levels and revive the kharif crops. The time is perhaps right to begin planning for the long term, harness and save available water over the year and avoid such crises from happening in the future.

(Disclaimer: This article, authored by Aarti Kelkar-Khambete, was first published in India Water Portal)

![[Exclusive] Vauld to seek 3-month moratorium extension as creditors panel explores bailout options](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/a09f22505c6411ea9c48a10bad99c62f/VauldStoryCover-01-1667408888809.jpg)