How these two women are reviving interest in Indian literature and art

Started by Onaiza Drabu and Prachi Jha, Daak is bringing back nearly-forgotten pieces of Indian art and literature in a manner that appeals to young people.

An essay by the Indian feminist Ismat Chughtai talking about being charged with obscenity; snippets from a deleted AIR interview of Che Guevara during his visit to India; a picture of the first Indian woman to fly an aircraft, and in a saree – these are some of the little known fragments of India’s old, still buzzing literature, art, and other movements that Daak is trying to revive.

What started as a reading group is now an organisation with a regular, eagerly-awaited newsletter and social media presence.

Started by Onaiza Drabu and Prachi Jha, Daak is bringing back nearly-forgotten pieces of Indian art and literature in a manner that appeals to young people.

Connecting two Indias

“The idea is to make this literature cool for the youth,” Onaiza says, “So many of us do not put the effort in to read these amazing pieces from Indian languages.”

“And more than that,” she says, “this neglect of languages and literature widens the divide between people who speak English and those who don’t. It worsens the other divides that these groups already have.”

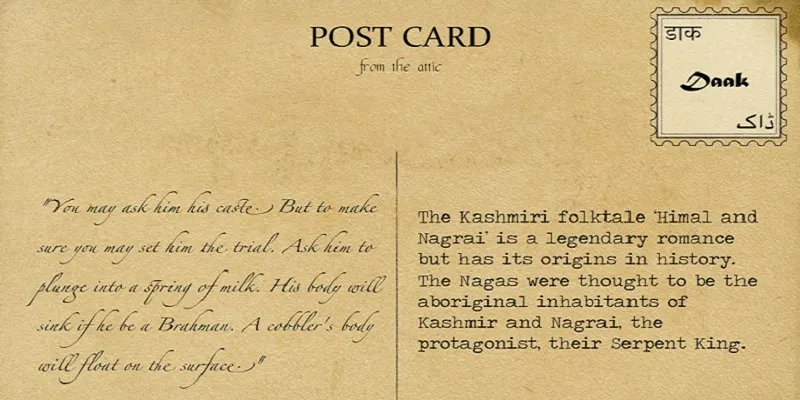

To make this material interesting, Daak uses some themes to tap into a certain nostalgia. Most of their posts are shared with a vintage look. For example, this extract from a Kashmiri folktale about the Nagas, aboriginal inhabitants of Kashmir:

This curation, Onaiza says, generates enough curiosity and engagement that people can pick up regional literature to read on a lazy Sunday afternoon.

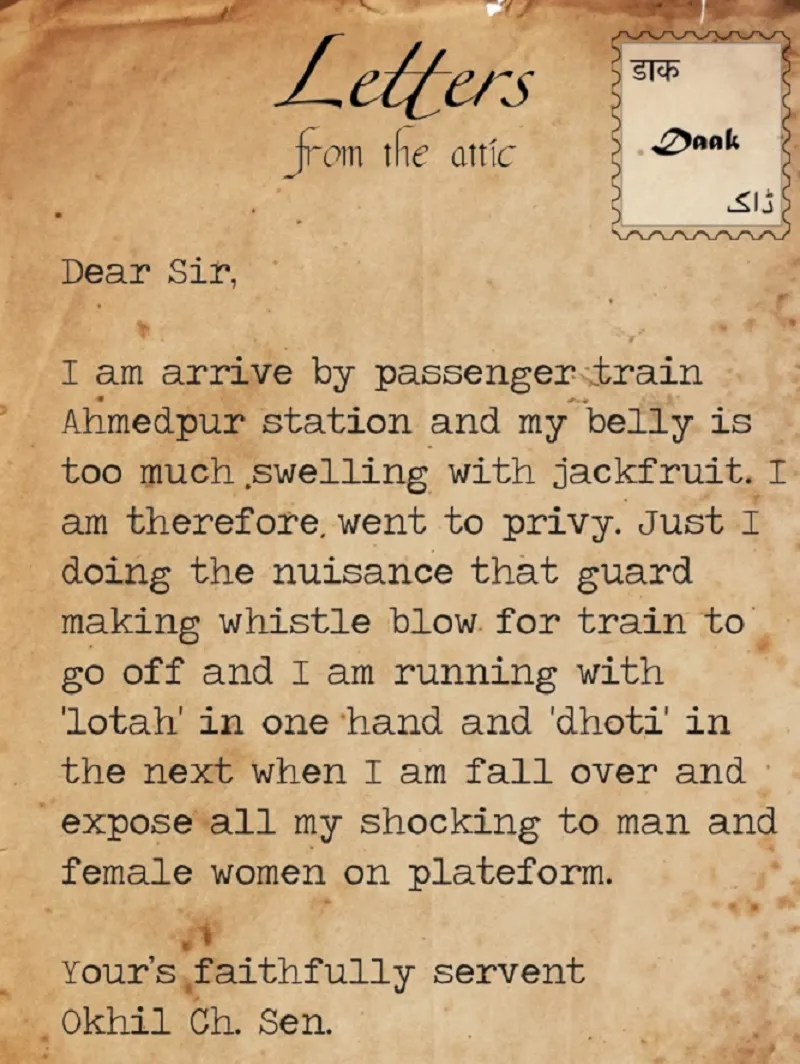

Apart from interesting pieces of literature, Onaiza also shares humorous records from Indian history. Here’s a letter written by a man responsible for toilets on Indian trains:

The letter is present in the National Railway Museum in New Delhi, but one would not have ordinarily come across it.

Bringing people together

Daak has a reading group that has read books in, or translated from, 20 different Indian languages. The most memorable book, Onaiza says, has been Dozakhnama: an English translation of a Bengali book about Urdu.

“That kind of cross-conversation across languages happens rarely now,” she says, “Dozakhnama was read in both languages. Those who could read Bengali had a very different perspective on the book, and we were lucky to be sharing that reading group with them.”

The reading group has an interesting composition. Most people are from South Asia, although a few are not, and are able to speak only English. While there are college students and professionals, the most surprising demographic for the founders has been middle-aged women. They are reading Amrita Pritam, Nayyar Masood, and Mahashweta Devi among others.

While the target demographic, young people, have responded enthusiastically as well, the most heartwarming feedback for Onaiza and Prachi has come from old men and women who have thanked them for bringing old memories back.

Next steps

Next, Daak plans to move from the Google Group to more physical events. This would mean more engagement with the content. Onaiza, who most recently worked for UNICEF in Nairobi, says there is demand for such a reading group even in that country. Prachi runs an NGO called Life Lab Foundation, that runs study tours and workshops.

How do they find the time to curate all this content?

“It has only been us doing the curating till now, but we are moving to a crowdsourced model very soon,” Onaiza explains. “Many readers reach out to us with suggestions on material to cover. We plan to formalise this process.”

“There are nascent plans to develop merchandise, as people have been demanding these postcards to be used as gift items. Some of these requests have come from as far as South Sudan!” Onaiza says.

Keeping sight of the purpose

Daak, Onaiza says, is a step towards removing the prejudices associated with regional Indian languages, which are also prejudices associated with class. “Regional languages are spoken widely, but in so many cities, their literature is looked down upon. Sometimes children are made fun of for speaking them in schools.”

Daak, then, attempts to introduce people to the wonders of Indian literature and its history.

Onaiza says, “What started as a space for us to discuss all the literature we were reading has now become a space to promote these languages and their literature. And now we hope to deliver Daak week after week.”

![[The Turning Point] How Oxyzo stepped out of its parent company’s shadow with India’s largest ever Series A fundraise](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/40d66ae0f37111eb854989d40ab39087/ImagesFrames36-1649423193276.png)

![[Startup Bharat] How Jharkhand-based LFYD is helping local businesses compete with retail giants](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/70651a302d6d11e9aa979329348d4c3e/Lfyd-1631173429675.png)