Ajay Shah — the 'bit player' in the Indian financial reforms

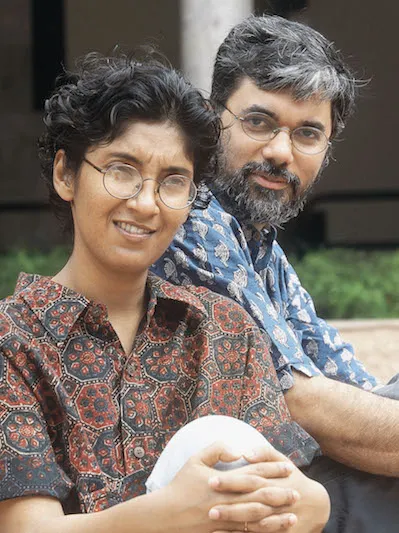

Ajay Shah and Susan Thomas co-created the mighty NIFTY 50, the flagship index on the NSE.

In a democracy there will be different views. I never resented the fact that there exist people who have a view opposite from mine. In fact, it was fun to debate with them. We would stand up in conferences, and argue. That's how ideas changed and an entire community altered its position. By and large, the entire Indian finance community started understanding and agreeing that instead of our old ways of doing ‘Badla’ (an indigenous carry-forward system invented at BSE), we should move on to electronic derivatives trading at NSE. It's safer, and we can have more control. We did not claim that it’s good just because it's done (practised) elsewhere. We debated on first principles and argued from scratch.

That’s Ajay Shah for you, the half of the power couple — Ajay Shah and Susan Thomas — who gave India NIFTY 50 (besides many other financial reforms). NIFTY 50 is a diversified 50 stock index accounting for 12 sectors of the Indian economy. Over the years, NIFTY 50 Index has shaped up as a largest single financial product in India.

I first heard about Ajay while interviewing Viral Shah, the co-creator of Julia Programming language. Ajay is Viral’s mentor. I was looking forward to my meeting with Ajay as it’s been long since I met an academician, that too from Public Policy background — six years to be precise, since I left my project in Public Policy to join YourStory.

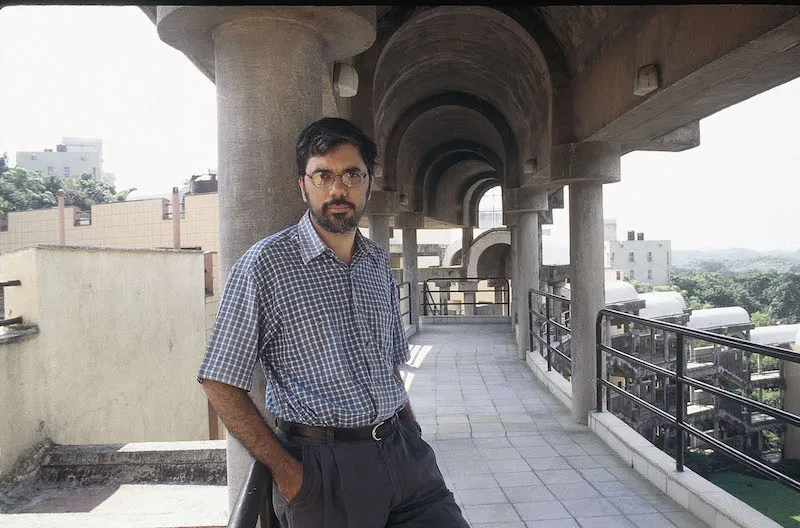

I was excited and may be a bit nervous, with the kind of jitters you carry while speaking to a professor. I met Ajay at his house in the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR) campus. That has been his residence for more than two decades now. Susan and Ajay live with their three cats.

Ajay is our Techie Tuesdays’ star for the week. He is a rare combination of a public policy academician and change agent; a mathematician and a programmer put together to solve larger problems of the economic and financial world.

An IIT Bombay and USC, Los Angeles, alumnus, Ajay has held positions at the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (Mumbai), Indira Gandhi Institute for Development Research (Mumbai) and the Ministry of Finance. He now works at National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP).

In this week’s Techie Tuesdays, we speak to Ajay about his education, research and the work that went into building NIFTY 50.

Also read - Meet Vasan Subramanian – CTO Accel Partners, India – the man with an everlasting itch to build tech products

The conversations shaping his childhood

Ajay grew up in Mumbai. His biggest single influence in his childhood was his father who was a thinker, an intellectual, and an economist. Ajay recalls,

Right from the very beginning, he was looking at the world, thinking about it, and I had the luxury of having conversations with him.

Ajay knew that for his father, the purpose of our existence is to understand the world, and in our own insignificant way, try to alleviate its suffering and make it a better place to live. Ajay imbibed this belief from his father. Thereafter, he got deeply invested in the 20th century history and politics of India, and the grand controversies around the Indian independence movement.

Ajay lost his father at the age of 17, but he considers those early years spent with his father as the defining period for himself. He says,

I walked out of it with a mixture of dreams of reason, of the extent to which one could think about the world, and could use rational analysis to understand the world.

Related read - Meet the chief architect of Aadhaar, Pramod Varma

IITFort

Ajay went to IIT Bombay in 1983 to study Aeronautical Engineering. But what excited him more was Computer Engineering. At that time, computers were relatively rare at IIT Bombay. There was one Russian IBM 360 clone where students wrote programs with punch cards. Then came some of the first BBC Micros followed by Z80 CPM computers. In 1984-85, the first microcomputers started coming in to the college, and soon after, arrived the first IBM PC. Ajay remembers programming for them in Turbo PASCAL. He adds,

I think of myself as a child of the early days of UNIX and the microcomputer revolution. There was a clear opportunity to reinvent lots of things about the world by using telecommunications, computer networks, and CPUs. I got Moore’s law very early. I understood that if we could dream applications today, they would become ubiquitous tomorrow. It was great to be a part of that revolution and to be able to understand what one could do with computers and Unix and the internet.

Slightly before Ajay started at IIT, a variant of FORTRAN 77 was implemented at IIT Bombay. Prof Dhamdhere had built an interpreter and in core compiler for FORTRAN. He came up with an innovation which would keep compiler in the core permanently and avoid inefficiency of multiple load-exit. Thus, it would read the FORTRAN program, write the compiled program into core, give execution, and then the control would come back to the compiler. The same philosophy was later on followed by Turbo PASCAL. The one developed by Prof Dhamdhere was called IIT Fort and was used to teach first-year Computer Science students. When he was in the third semester, Ajay along with his friends decided to write a book on IIT Fort which was published and sold across the campus.

The two-winged brain

Ajay thinks that his brain has two parts that he nurtures:

- The part that lives in Mathematics and Computer Science which makes him a child of the world of science and reason.

- The other wing lives in the world of politics and thinks of the state, public policy, and ways to fix the world.

He adds,

Compared to many people in the world of science and engineering, I'm more interested in politics. And compared to most people in the world of politics and public policy, I tend to have the internal capabilities of doing maths and computer engineering. I'm equally comfortable in the world of science. I carry both the cultures — humanities and social science; and science and engineering.

Related read - Story of a programmer who fell in love with Hindi poetry — Satish Chandra Gupta

“The drama, the glory, the ignominy, the fury, the spectacle of the world is what keeps me going”

After IIT, Ajay pursued PhD in Economics at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Ajay thought that studying Economics would be a good way to amalgamate varied knowledge as its interdisciplinary nature involves philosophy, ethics, history, politics, and applied Mathematics. Ajay adds,

I think of John Maynard Keynes as one of my heroes. He was always deeply rooted in the issues of the world and cared about it. That's the kind of role I saw economists doing. I find myself driven by the world. The drama, the glory, the ignominy, the fury, the spectacle of the world is what keeps me going.

During his PhD, Ajay also worked at RAND Corporation, the global policy think tank in Los Angeles. He worked in ageing research, solving the policy problem of old people in the US.

Though Ajay learned a lot of tools while pursuing PhD, he considers it phenomenally sterile as it was far from his idea of fun. He says,

I feel disappointed that economists have the opportunity to matter far more, but so much of academic economics is just about narrow specialisation and learning everything about nothing.

Ajay finds economists building real-world systems more interesting as their work is real, applied, and meritocracy-driven — for example, the economists inside Amazon, eBay, Google, or the ones in the world of algorithmic trading.

The great Indian reforms call for return

Ajay finished his PhD around the time when the great Indian reforms had begun. It made him think of going back to India and be a part of all that was happening. He moved back to India in 1993 and spent some years at the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), Mumbai which works on building databases — on firms, geographically-distributed information, on overall economy, and on households. Ajay’s role at CMIE was about thinking what kind of databases and applications could be built.

At that time, IT systems were a big challenge, and Ajay had to apply his mind on thinking about the computational stuff that would happen on building databases, storing data, and analysing it. That was still the early phase of the computer revolution in India.

CMIE had been building firm database since 1984, but only around 1995, the database started to go to the customers in electronic form (through floppy discs). CMIE would supply an application program which would run on top of that and enable the customer to query the database. It was then a remarkable and a revolutionary thing.

CMIE also had the first stocks returns database. Returns is the percentage change in the stock price from today to tomorrow. Before CMIE, nobody had that data and it was quite a challenge to make those databases.

In 1995, Ajay moved to Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR), Mumbai. Susan Thomas, Ajay’s wife, also finished her PhD and moved back to IGIDR. They've been staying there since then.

(Note: Susan is currently a faculty member at the Indira Gandhi Institute for Development Research (IGIDR), Bombay. She has also served as a member/chair of various committees constituted by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) and the National Stock Exchange (NSE) on secondary markets, government securities, and foreign exchange.)

Related read - Milind Borate – the man building the ‘North Star’ of data protection

The outsiders who were treated as insiders

Around that time (1995), NSE project was starting up. Ajay recalls that R H Patil, who was the leader of the NSE project, was very welcoming and supportive. Even though Susan and Ajay had no formal role in the NSE project, they had the luxury of being treated as insiders and were invited for discussions. Ajay and Susan were a part of the early days of NSE where they dreamed of electronic trading, stock market trading, rules of the games, institutions, safety, and how to build risk management. Ajay says,

We had the privilege of being the bit players in the grand story. It's a recurring theme for me — to play a minor part in a great story. I've always chased that.

According to Ajay, NSE was the most important piece of the Indian financial reforms. He adds, “Following the logical development at NSE, first the electronic trading happened, then equity market started stabilising, and after that came the question of derivatives trading. When you think of equity derivatives trading, the logical question is to do index derivatives trading.”

NSE was a pioneer in the 1990s in electronic trading, as NYSE and London Stock Exchange still had floor-based trading at that time. NSE asked Susan and Ajay to construct an index that would be well-suited to the challenge of derivatives trading. Ajay recalls,

That question was not really asked before in the world. Generally, elsewhere, the index came first and derivatives trading came later.

Equipped with a unique database because of electronic trading, Ajay and Susan could see that the observability and the legibility of trading process at NSE was superior to what was prevalent elsewhere in the world. They started working on the methodological design of NIFTY. Ajay says, “On a larger meta theme, it's important to think for yourself, to solve problems from scratch. I see many people who want to blindly copy. I think you make progress by thinking from scratch.”

The famous political scientist and anthropologist James C Scott has written a book called Seeing Like a State — in which he coins a word 'metis' that refers to ‘deep experiential local knowledge’, i.e. think of your neighbourhood, look around you, apply reasoning from first principles, and solve problems. Ajay believes that he took the same approach with NIFTY which proved to be the winning strategy.

The ‘50’ in NIFTY 50

To come up with NIFTY 50 index, Ajay and Susan took the following two observations into account:

- The gains from diversification in the number of stocks in an index taper out quickly. So, you get diminishing returns as you add stocks into an index.

- If you've an equally-weighted index, then the standard deviation goes down in proportion to 1/n. But in an index, the stocks are weighted by market cap. So, when you add 100 more stocks, then those from 50 to 100 carry little weightage (almost 10 percent) and make a small difference.

So basically, one had to be careful w.r.t. diversification; though it reduces the risk, it may lead to diminishing returns as well. Also, when you make the index bigger, you will encounter problems in being able to trade the full index. Ajay explains,

The unique thing in the modern world about an index is that you'll run index funds on it and trade index futures on it. The index futures guy would want to trade all n number of shares in the index as a basket doing a portfolio trade. So, you need to think about the cost that will be suffered by those guys.

Ajay and Susan could simulate cost of transacting (for NIFTY index by a person doing index futures arbitrage or running an index fund) using the data from the NSE order book as the data was electronically available. They worked with NSE to capture that data and managed to get a large mass of that data. Ajay recalls, “With the computers of those days, computation was a big challenge. We were geeks, so we wrote codes to study the whole thing. I wrote a C program because anything else was too slow to do such things during that time.”

Ajay was able to write a pair of simulations exploring the following:

- How diversification comes about as we change the design of the index and where do you get the diminishing returns on the diversification.

- How the cost of transacting changes with different designs of index.

Putting the above two together gave the answer — 50, the size of the index. That was the main outcome of the project and methodology.

Revisiting the trade-offs

Ajay and Susan wrote the code for simulating the management of the index, computing the diversification gains of the size of the index, and the measurement of the index cost. It took them three months overall and they wrote all of the code. Ajay says,

It was herculean task and we worked like dogs. There was no staff or team or support. Every little secretarial job was done by us.

NIFTY has been successful, and increasingly, the attention on NIFTY is in terms of the product. Today, more than half of the NSE activities are on NIFTY futures and NIFTY options. The index fund industry around Indian indexes is entirely NIFTY. The participatory notes and the derivatives overseas are all on NIFTY. More than two decades later, Ajay expresses his interest to revisit a lot of trade-offs (made in designing NIFTY 50). He says,

In 1996, we looked at it(approach) from first principles. Today, in 2018, we are stuck at the old design decisions of 1996. We should be really taking a fresh look at the entire set of design decisions. I suspect today we can do much bigger index because the Indian stock market is so much better. The technology and the liquidity will permit much bigger index transactions.

“There's an algorithm that manages NIFTY and that algorithm was designed by us. And those trade-offs of 1996 are in that algorithm,” he adds.

You may also like - How Akiba is cultivating the maker-hacker culture in the countryside

Not the ‘normal’ academic

Ajay and Susan later became a part of policy process around derivatives trading. Ajay recalls,

There was a lot of controversy in India. There was curiosity and hesitation about (derivatives) trading. We were happy to keep teaching, evangelising, and explaining. It didn't fit the work of a normal academic. I should have been sitting and writing papers.

NIFTY derivatives trading started in 2000 and the rest (other derivatives) in 2001. By then it was five years since Susan and Ajay started going around teaching and evangelising derivatives trading. Meanwhile, Ajay kept answering the tech support questions sent to him by almost anyone, over email, just for fun. He says, “It helped me understand what people were thinking and how they were understanding the world."

With the derivatives trading kicking, there was a lot of interest in it from the policy side. Ajay was invited to be an expert in front of the parliament’s standing committee on finance, which was making the decision regarding whether to amend the law to support cash settlement required for index derivatives. Ajay presented to the then Finance Minister P. Chidambaram in 1997.

Soon after that, Ajay’s next chapter of life started in the field of pension reforms and policy.

(This is part 1 of Ajay’s story. Watch out this space for the second part.)