Buttering the right side

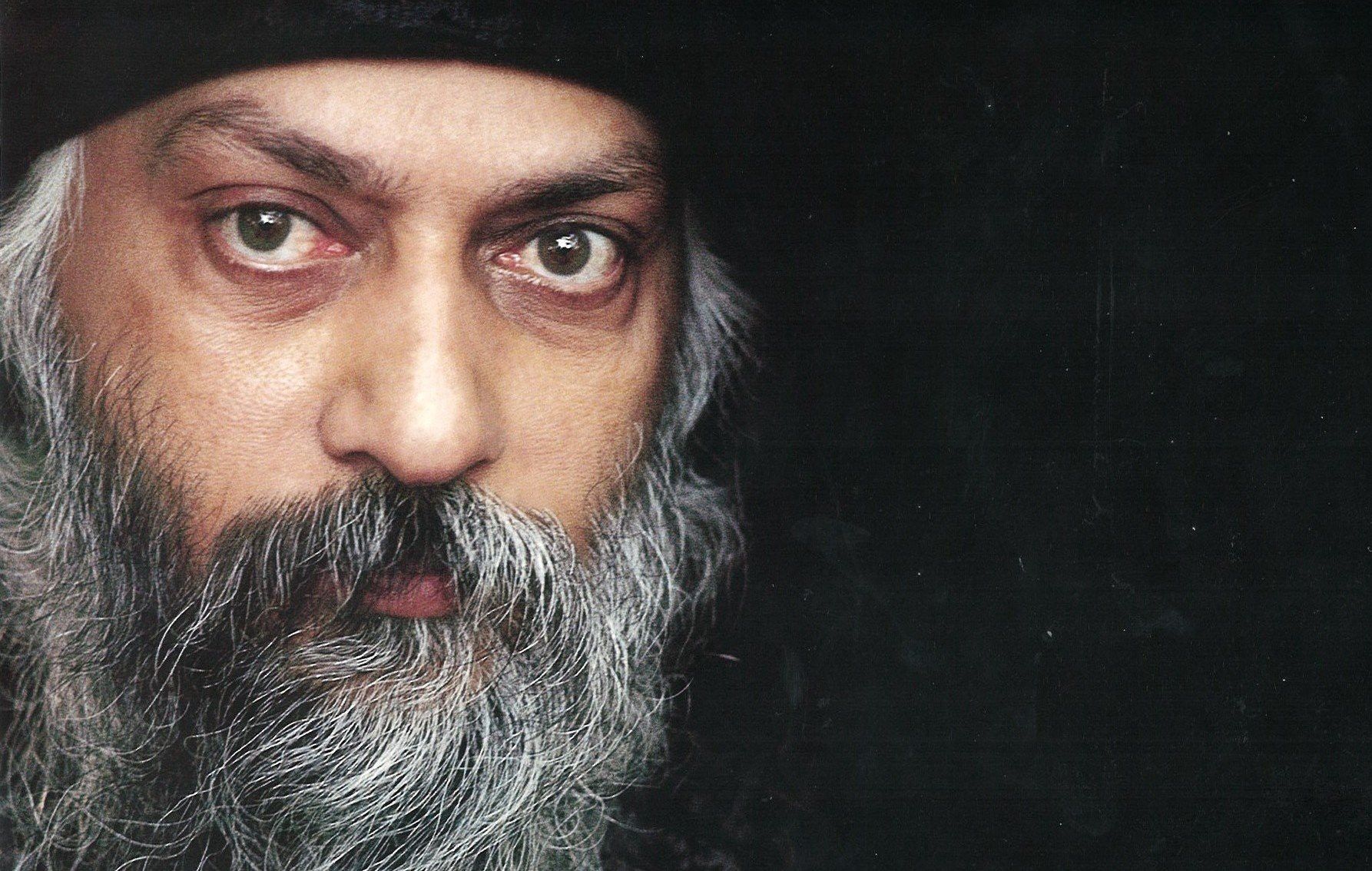

Mr. Rajmohan Krishnan's recounts how Entrust Family Office came into being

Monday January 02, 2017,

9 min Read

There is no doubt that a wealth manager should be client-aligned. But can he be?

Trust is paramount in any relationship, be it financial or professional. But is this self-evident statement true in the relationship between a client and his wealth manager? While the client expects the wealth manager to butter his side of the bread, will the wealth manager mind if his client turns into toast?

That’s a loaded question. To answer it, we have to travel back in time.

The era of ignorant investments

Way back in 1996, I was asked to set up the business for a pioneering financial services firm. That was a different era. Wealth management was called retail financial services. Wealth was hardly ever in the hands of youngsters like it is today. Clients tended to be retired folks or businesspeople. Most of them also happened to be investing for the first time. To cater to forecasted demands and to professionalize the industry, many of the top NBFCs that were setting up shop in metropolitan India hired MBAs and veterans from various industries. If one looked smart and talked smooth, one could sell financial products. Or so it seemed.

Chennai, where I was based, used to be far richer than Bangalore. The city stood out for the faith it reposed on the largely unregulated chit fund industry. To investors in those products, investing with NBFCs might have been a mere extrapolation of their financial ideology. This mentality was partly responsible for HNIs in Chennai investing in almost every NBFC.

As investor enthusiasm rose, so did the need to educate them. That was the time when the transition from Fixed Deposits to Mutual Funds took place. People had to learn terms such as debt fund, liquid fund etc. They weren’t aware about the interest rate volatility or the risks accompanying the purchase of equity funds and a few of them were close-ended funds with no exit. They could be forgiven for not knowing that AAA ratings could be managed.

Till 1998, only about half a dozen mutual funds had been launched. And all of them were launching new funds and were called Initial Public Offering, like that of Shares in public markets. Of course the markets were on fire and every broker in town was able to easily double the money invested within a quarter. In the stock market, operators were ruling roost as they used to write forward-looking reports and underwrite stocks to encourage sales. Small and large investors, for the first time in their lives, moved money out of FDs. Greed took control of people who did not understand that stocks were being purchased against their mutual funds, and that stock prices could plummet.

Not many could fathom such a possibility when the market was delivering beyond anybody’s expectations. For example, khoj.com was sold for an astronomical premium. Meanwhile, there were loads of IPOs hitting the market and brokers sold them like there was no tomorrow. Every financial services company had a field time selling new funds from the Asset management companies and also the IPOs. It was a lucrative thing to do, with a 3-4% upfront pay-out. Neither the employees of these financial services firms nor brokers and investors would want to dwell and understand the underlying risks. Sound investment advice was prominently absent. In those heady days, I came across very few professionals who made effort to sit with the client to explain risks and suggest a coherent investment strategy.

A conflict surfaces

In 1999, after a successful 3-year stint, I moved to another financial services firm. I was determined to take their financial services to the next level. Within a year, I performed quite well. I was especially lauded for handling a deal that put several crores in the pockets of each of the five promoters of the firm that got taken over, and in those days these sums were unheard of. The promoters asked me to invest their entire gains in risky investments including equities and a few fixed income schemes, as the market was heading northwards. No thought was given to asset allocation and we, as an organization, were not talking that language either.

When the dotcom bust of 2000 happened, my investors lost substantial monies of their capital due to their greed and our shared ignorance. At the same time, they realized with a shock that firms like ours made money even when they lost their shirts. I was also becoming aware of the lack of transparency in my domain.

On the one hand, I was a star seller for my firm. On the other, I ended up having quite a few disgruntled customers. Tasting huge losses, all of them exited these loss making investments and, chose safer options like RBI bonds and FDs. Despite all this not many learnt to diversify their portfolios.

I was left pondering over what could have been.

The next phase

In 2001, I moved to Bangalore where the IT industry had started to blossom. Media reports were celebrating the existence of dollar millionaires amongst Infosys employees. In this backdrop, I was trying to make my peace with the uneasy realization that my loyalty was not to my client, but my paying employer.

Wealth management (or Private Banking as it was called then) brightened again in 2004. Brokerages used their client base to set up private banking and they began to talk about asset classes and allocation instead of just stocks and portfolio management schemes. Employee salaries were also burgeoning. Organisations had to generate revenue in order to keep their profits higher as well as keep the employee morale high in order to retain good professionals. One of the most recommended instruments to invest was mutual funds, as the AMCs incentivized the private banks by paying high commissions and also offering foreign junkets etc. In a bullish market, this was par for the course.

Meanwhile, new fund offerings christened as Mutual fund IPOs were flooding the market. The AMCs were allowed to charge a prohibitively high marketing fee for these IPOs and a lion’s share of this was being passed on to the Financial service firms selling these products. With short term capital gains tax being nominal, the firms churned the pot well. The client used to always believe that the dip in his net asset value is mainly due to the high entry load. This practice continued till the loophole was fixed a few years ago.

As days went by, the product pedalling scaled a new peak with the advent of new inventions, like Real estate funds and Private Equity funds. Though these products were quite innovative for those times, they were sold to clients like commodities without assessing the risk taking ability of clients. The long tenured products, which has not seen the light even after 9 to 10 years, were sold luring the clients with the bait of attractive returns, but most of the clients didn’t bother about the fee structure which included a placement fee, a management fee, a profit sharing fee not to mention taxation on the returns. Many funds launched by various financial service firms has only delivered sub optimal returns considering the long tenure and the fee paid by the clients. This process continued till 2009 and by that time most of the damage was done. It was unrealistic to expect client interests to be taken into account in such business models. HNI clients invested heavily in these close-ended funds that required a minimum investment of anywhere between one million to two and half million rupees. With the terms of the offer heavily favouring the firms, clients got ripped off and are yet to recover their money.

In this era, I vividly remember how an 85-year-old client was convinced by RMs to invest in products with a 10 year lock-in period. This violated the basic need to match products to clients. One client’s goldmine could well be another client’s dungeon. So how could a client who deserved liquidity be sold a product that was better suited for fresh-faced IT professionals? The reason: revenues.

One cannot blame the organisation alone for these excesses as the relationship managers got carried away by the lure of high commissions and incentives. Private banking became a money game with high stakes and continues to be that way even today. Organisations today purchase Relationship Managers from the market, paying hefty salaries, sign on bonuses, stock options all of which act like golden hand cuffs to retain the employees. And in return, the employees will have to ensure that they justify the benevolence bestowed on them, by making revenues which necessarily will have to come from product commissions.

Wealth managers, across firms, me included, were under tremendous pressure to meet our monthly and quarterly targets. So we got into the habit of dumping monies into the market the moment clients released it. It didn’t matter whether the market was going up or down. We couldn’t wait an hour, let alone a day. We just wanted to login our investments and get our backs patted by our bosses. After all, as I said before, our loyalties lay with our employer.

Honestly, the system I was part of was taking a toll on me. I had had enough of all this and felt that it was time to refine and redefine who I was in my eyes and in front of my clients. I understood the meaning of the saying, `A guilty conscience pricks the mind.’ And in 2012, I decided to call it quits with this industry and begin to truly service my clients. This would be my way of giving back to society.

The genesis of Entrust

Entrust Family Office began due to my intense desire to act on behalf of my client and nobody else. The experiences of the past played on my mind so much that I felt, this is the only way to go if I wanted to continue in this business.

Over a period of time, one starts developing a warm relationship with the client. One learns about their family, personality, dreams and aspirations. And so many clients trust wealth managers such as me implicitly. One feels responsible, answerable. It was killing my conscience that I wasn’t acting in the best interests of my client. The best way to do so, I felt, was to create a new modus operandi.

One that made the investor happy and prosperous, ensuring a long-term relationship with Entrust Family Office. So doing the right thing also made business sense.

Today, we work with HNI clients who are the only people paying us. The conflict of interest is, therefore, eliminated altogether. We help them consolidate, minimize complexity and create a solid succession plan. And while we give them every reason to trust us, they optimize their time on their core competencies.

undefined