No direction home: Racing through Rajasthan during the lockdown

As Dhawal Trivedi rode through colour-coded zones, he discovered many perils, thrills, and existential undertones of the lockdown. Here is a first-person account of his journey through Rajasthan amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

A native of Banswara in Rajasthan, I work in a non-profit research institute based in New Delhi. The national capital has been my second home for half a decade. Like millions of other migrants during the Lockdown-1, I was longing to go back home.

Dhawal Trivedi

When the Lockdown-2 commenced, I was informed that I had become an uncle and was impatient to meet my new born nephew. As the Lockdown-3 rolled out, like a migratory bird, that is compelled to fly, I took my bike for an 800-kilometre ride through colour-coded zones.

As the world is rallying together to flatten the curve of the novel coronavirus, here's my tale of discovering the perils and thrills of inter-state travel in the times of COVID-19 pandemic.

Where it began

The highways were deserted

I believe it all began sometime during the third week of lockdown with my rekindled interest in Michel de Montaigne’s voluntary isolation. Retired to his tower in Bordeaux, Montaigne kept on writing, functioning, and living while life itself was under attack of a plague in the 16th century.

Self-isolation and quarantine can be heavier burden for those, young or old, who live by themselves. We all wear social masks but often there is a gulf between who we are with others and who are alone. Being with your thoughts doesn’t affect you, it defines you. But like Montaigne, I’m accustomed to the company of my heavily populated solitude.

In these distressing times, one seeks distraction. After a few despairing and unsuccessful attempts to get e-pass for movement from state governments, I had almost given up hope.

Ready, get set, go

On the afternoon of May 5, I received a call from the District Magistrate’s office in Southwest Delhi. The directions, from the voice on the other side of the call, were clear: Reach a DTC bus depot in Dwarka within an hour, a medical screening will be conducted, and the district officials in Delhi will issue a movement pass—all at the behest of my application to the government of Rajasthan. There was no time to gather my thoughts so I reached there in haste.

Thermal screening

Much to my dismay, there were no officials at the scene. Those who were present didn’t have any clue. In the next few minutes, more people gathered in the shared hopes of obtaining their movement pass in lockdown.

The depot staff asked us to stand in a socially distant queue while they tried to streamline all the confusion and start the screening process after an hour. Despite being the first one in line, I waited two hours to undergo thermal screening and collect the interstate travel pass for my two-wheeler.

After having dinner came the hour to convince my near and dear ones. My partner, who has great psycho-social insight and foresight, wasn’t pleased with any of this. My sheer recklessness to leave was propelled by verbs—like can, will, and must—that failed to connect with her.

The next morning at the stroke of 5am, I revved up my bike to set sail on the memories of home that was 750 kilometres away. After the first check post at Delhi-Gurugram border, I looked back only to admire the pre-dawn pink hues that coloured the concrete skyline of NCR.

After that, I was in a trance; it was me, my bike, and the road. Or so I thought.

River of my people

A caravan of people was fleeing NCR for their homes. Looking at them closely, some surprising truths emerged. Those who have watered our plants, cleared out dustbins, fixed appliances, and dug the foundations of our cities of tomorrow, were now stranded, and couldn’t afford to turn back — and the road seemed to have become their purgatory.

Migrants wait for passes

Many of those — bereft of any sense of belonging anywhere and moving at a plodding pace — were too tired to raise their arms or ask for ride. I felt deeply saddened at seeing their unmasked faces with expectations abandoned, defeats accepted, and several griefs borne.

There was no screening of any sort as I sneaked into Rajasthan. After riding for another 10 minutes on my home turf, I decided to hit the brakes for a while. All this while, my brain kept wrestling with questions about my safety.

My backpack had an appropriate change of clothes, three bottles of water, fruits and leftover dinner for lunch, a handful of biscuits, a laptop, and essential documents.

A storm along the way

As I was approaching those medieval battlefields of Jaipur, the air turned suddenly warmer. It was not even 9 am yet; it must be the Urban Heat Island effect I keep hearing about.

After bypassing the entire Pink City kept under strict lockdown, I found a dhaba on the highway where pagdi-wearing locals were sipping their morning tea and discussing last night’s rain. In four and half hours, I had 300 kilometres behind me. The air of late morn felt crisp again on my face and I could hear some birdsongs along with the deafening silence of the NH 8.

Before gulping down bananas and one whole Good Day biscuit with my first cup of tea, I informed my father who reminded me to curb my enthusiasm and literally cool my jets. I convinced him that, at this rate, I should be home by sunset.

Three state government buses carrying stranded migrants drove past. The interplay of clouds, drizzle, and mild sunshine was a relief for a while. During that ride, a car crash near Dudu was the only scene that startled me. The fuel indicator began to blink as I finished about half of my homebound ride.

After refuelling my metallic beast near Ajmer, I could no longer delay first ominous signs of fatigue and hunger. Since I was running ahead of my imaginative deadline, it was time to make a second stop.

Leftover fried rice and sugary tea went down smoothly in five minutes. I momentarily crashed on a charpai. The curious motel owner and a teenage waiter, who wouldn’t accept a tip, asked if things were slightly better in Delhi. I wasn’t too sure about the 200 kilometres of my journey ahead, so they gave me directions and details of the road conditions too.

An hour of suspended animation

And thus, began the least enjoyable period of this arduous ride. Soon as I strapped on my imaginary seat belt, the dialogue with road turned into monologue. The nondescript towns, rushing past in top gear, brought no help either. The wind opened up the blue sky, out came the sun to roast me. Each pothole, which I couldn’t avoid, rattled my limbs like Tupperware. My plan was simple: to take it easy but take it.

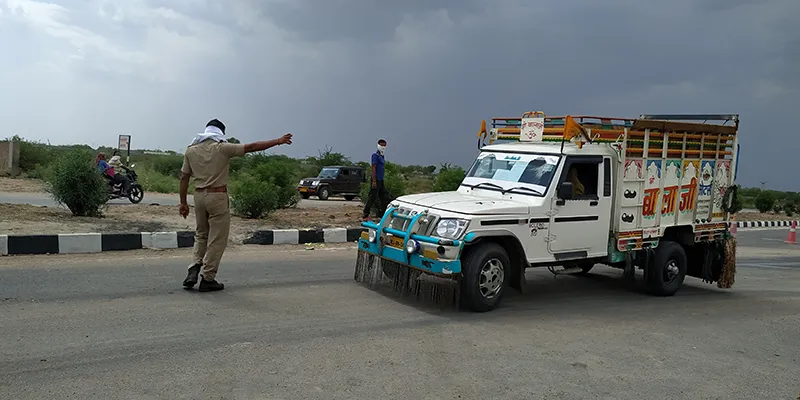

A check post in Bhilwara

When I rolled into Bhilwara, I was delightfully disoriented to even realise that peculiar and familiar stench of the textile mills was missing. Then at last around 2:30 pm, I was thumbed down by a policeman, for the first time since Gurugram, who more than anything was curious to find a Delhi license plate number in Rajasthan.

Just as I showed my pass to authorities, my phone rang. I let my family know about my whereabouts and safety. After relentless convincing and in light of a circling storm, I agreed to their proposal to meet half way from home that was still at least four-hour ride away.

From there on, reaching Chittorgarh was a ride of desperation in high noon. At the next toll plaza, I was instructed by police staff to steer clear of some hotspots and containment zones. I could see crops burning in the distance and the emptiness of horizon ahead.

Eventually, a momentary lapse in concentration on the road led me to the border of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh—where a familiar scene unfolded of migrants waiting to be sent home. I gave away some fruits, biscuits, and snacks, and water to those walking alone.

When I left the highway for rural roads, police check posts became a lot more frequent. The storm eventually caught up with me. I took shelter under a flyover, parked my bike safely, and crashed on the backseat of car when my father arrived moments later. While echoes of the engine were still ringing in my head, my father issued a commandment, “Thou shalt not return to Delhi on the bike.”

The day was far from over

Though I was screened for temperature three times in 24 hours, we went straight to the district hospital to get my tests done. After my arm was stamped with mandatory quarantine, we walked through a poorly lit alley, where medical waste was lying in open, to find the COVID-19 isolation ward.

Final destination in sight

The medical staff handed over swabs and testing kit to our batch of 25. When I was called up by the doctor for documentation, his younger assistant asked me to take off my mask and face cover. I followed his instructions because I was too tired to think otherwise or hold up the queue. The assistant whispered to another colleague with a smirk, “Oh, thought he was one of those.”

At a time when innate prejudices run high, I did not react. In his unsettling perspective, I was just another bearded migrant from Delhi in a pandemic.

Home, at last

After a day of crescendo and diminuendo, I was home in time for dinner that never tasted better. I went inside after disinfecting and sanitising my backpack, clothes, hands, and exhausted soul. The next day, I hugged my infant nephew for the first time—the sole purpose of running to Banswara, my home.

At the time of writing, I have been thermal screened four times, local village officials with medical staff have checked in on me five times in a week, I have not crossed the threshold of my home, and my COVID-19 sample tested negative. I’ve been asked numerous times how I calmed the tide of nerves, and each time, I iterate Michel de Montaigne’s skeptical remark: Que sais-je? (What do I know?).

In prolonged periods of vulnerability, we want to be surrounded by familiar people and places. Events from two months ago in pre-pandemic Delhi now seem like they occurred years ago. My last social engagement was in March: a post-work evening walk in Central Delhi with my beloved. We parted ways not knowing we wouldn’t see each other for months.

A new world

I am not a keen observer. But the ubiquity of suffering would even bring a tear to emotionally illiterate. I rode a highway with no secrets to conceal. I saw a child holding on to his parents like a leaf clings to a tree. I crossed a bridge to nowhere and with nobody on it. I left behind a bus full of men with bleeding hearts. I met souls wounded with fallacies of hope and the awareness of the brevity of existence.

Homesickness is a great tutor. About a month ago, I heard a saying that stayed with me... “In this terrifying world, all we have are the connections that we make.”

Today, I find myself in the privileged position to be in mandatory quarantine with my family of five. Pregnant with this newfound wisdom, I imagine telling my newborn nephew someday about how we spent the first few weeks of his life.

Edited by Asha Chowdary

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory.)