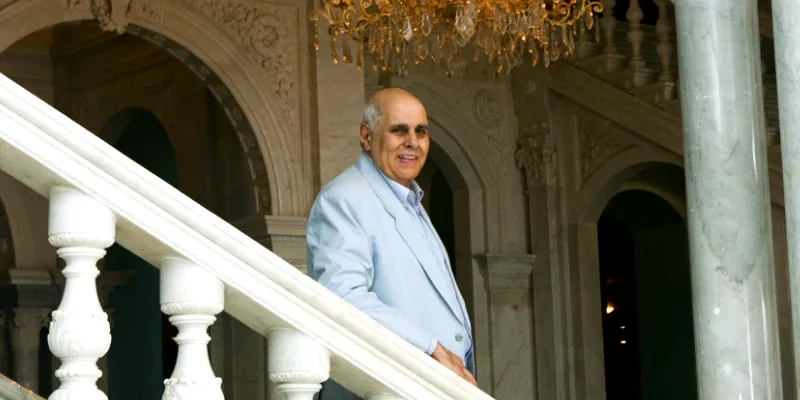

Meet the man behind Bisleri in India, who started up again at 70

The curious case of Khushroo Suntook... One would think that the maestro's career peaked when he crafted a brand that the best of us have absentmindedly demanded from a shopkeeper when we really just meant to buy bottled water, but the 81-year-old is still effortlessly adding his strokes of genius to India's entrepreneurial canvas.

Khushroo Suntook’s family – residing in Mumbai’s plush Malabar Hills for generations – is a clan of illustrious lawyers who have graced it all from the judge’s bench at the Bombay High Court to the board of Mulla and Mulla. His mother, in turn, is the daughter of Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, Fifth Baronet.

But they were more than just Parsi business royalty – they were aficionados of the finer things in life. Thus, leading a quintessential Parsi childhood immersed in song and sport, Khushroo wielded his tennis racket with as much tenacity as he swayed to the sounds of Tchaikovsky, Strauss and Beethoven. His mother and grandfather, after all, played the piano, and his father, a solicitor to multitudes of foreign clients, always scored a record or two from his overseas friends for an ever-so-eager Khushroo, thus fueling what would come to be a lifelong hobby of collecting records.

But even as his love for tennis – which he saw to fruition playing at the state and national levels – and the piano, which he trained in for almost two decades with a prominent pianist, Olga Craen, stayed at loggerheads through his childhood, how entrepreneurship, an unprecedented wild card, prevailed was a curious, yet serendipitous turn of events.

Water out of thin air

You see — Khushroo was to pledge his allegiance to the profession all his forefathers pledged their lives to. He had studied advocacy and was ready to slip into the raven robes but Italian friends of the family, the Rossis, who owned a company called Bisleri (named after their mother who belonged to the Bisleri family), thought it was the opportune time to knock on Indian doors. Khushroo’s father happened to be a “custodian of enemy property” (properties seized from the Axis powers, of which, Italy was a part, during World War II) and, hence, the Rossis persuaded him to become an associate as they blitzed Bombay.

Bisleri was originally a company that made an anti-malarial drug, and had a small set-up on DN Road. While that was taken over, they still had the property and wanted to use the money to bring something revolutionary to India.

Dr Rossi, who had links to the doyens of South Indian trade like Venkataswamy Naidu, Devarajulu, thus commanded a certain level of tenability. He took Khushroo in confidence and got him in on his crazy grand scheme — to manufacture bottled water. The year was 1965. “He was a very powerful Italian, and a really dynamic fellow. The water quality back then was so bad in Bombay that people would get bad tummies. There was no bottled water available because it was all restricted in those days, and bottled water was considered a luxury. We had to break that misconception,” he recalls.

They also owned another company back in Italy that makes the wine 'Ferro China', and had bottling factories that also manufactured a sort of natural mineral water. In India, they established a factory in Thane’s at Waghle Estate. The water is first demineralised, making it almost distilled, but since that is unfit for consumption because it has no minerals, they then add in small quantities of potassium and sodium.

“People thought we were quite mad. But we started making the product anyway, and roped in Voltas as our distributors,” Khushroo recounts.

“At first, they said, who’s going to buy water for one rupee! It was such a new concept. No one wanted to pay for water. But, slowly the hotels started taking them,” he recalls. There were times when Khushroo himself got his hand dirty, and delivered crates of Bisleri to Irani Hotels. The product found eventual acceptance, and Khushroo and his partners, in turn, got a lifetime’s worth of thrill out of traversing with the bottled elixir on its voyage from being a luxury to a lifeline.

An early second set

For three years, they were golden. But this hot-handed streak came to a grinding halt when an unfortunate incident took place in the Rossi Family back in Milan. While Khushroo refrained from divulging more, he stated that for superstitious reasons, they were forced to sell off their shares in Bisleri to Parle, owned and run by the Chauhan family, who Khushroo had come to know socially during his tennis days. “We were all extremely heartbroken, but we sold it to Parle and the rest is history. It was expected to do well, but alas,” he laments.

Still in his twenties and with that staggering list of qualifications and experience, for Khushroo, the game had only just begun.

READ ALSO: High street ‘hajamat’– how Istayak Ansari brought the 211-year-old Truefitt & Hill to India

Since his father was a director of several Tata companies at the time, he got the inevitable call from the Tatas bidding to take him off the market once again. “I wanted to join one of their smaller companies then. So, I joined Simone Tata when she was handling Lakmé,” he recounts.

He started in 1968, and worked with Tata Group in various capacities for 30 years – as director of Tata Oil Mills Company, Finance Limited, Tata Mcgraw Hill, Tata Investment Corporation, Tata Building, while also gracing the boards of Wadia Group’s National Peroxide, Council For Fair Business Practices, and the committee of the Cricket Club of India (CCI) for 25 years.

The pioneer’s stint with the Tata’s wasn’t lagging in opportunities to blaze trails, either. Of all the things he accomplished for them, their successful foray into Russian markets was something he is proud of steering. “In those days, we had the rupee trade with Russia, and in fact, to buy Russian goods, we had to barter our goods because they had no dollars to pay us, so we bartered a lot of cosmetics and pharmaceuticals — made very well by Serum Institute of India’s Cyrus S Poonawalla — especially an age-retardation drug they made. We also forayed into medical equipment — oh, you can’t believe the things we did! MRIs and the works — with Toshiba, who we eventually sold it to,” Khushroo says.

The initiation of the pharmaceutical division was bolstered by Khushroo through several collaborations with his associates in Italy. “They still have products in the markets which were created under my supervision – like Viscodyne cough syrup, and the Eclospan skin cream,” he exclaims.

The show must go on

Hard at work for more than three decades he might have been, but the audiophile in him remained well-watered through his extensive travels for work, from which he always returned with a prized record to embellish his burgeoning collection with.

“My interest in music was huge. My record collection grew leaps and bounds — in fact, I formed some amazing companionships all over the world over a shared love for record collection. Till three years ago, I spoke about record collection abroad. People would tease me that anywhere there was a good opera in the world, I had exported records to — Germany Italy, Japan, Russia, England, what have you,” he says.

After that grand career that spanned nearly three and a half decades, in 2000, Khushroo, aged 65, didn’t ask for an extension and decided to hang up his boots. But his friend on the fourth floor of the Bombay House, Dr Jamsed Bhabha, the Founder of NCPA, had other plans for Khushroo.

“Our families went way back, and I would frequently go up to Dr Bhabha and talk to him about the NCPA, until he finally invited me to join the council and chair it,” he says.

Starting up at 70

When he was still the vice-chairman of the NCPA, he was attending a Kazakh orchestra in London, circa 2004. He was so enamoured by their music that he approached the orchestra backstage immediately after the concert. “I had this mad idea to invite them to play here in Maharashtra. Two trips with their orchestra and we thought of an even madder idea — to start a professional orchestra here in India!”

It blossomed into another one of those companionships formed over a love for music that Khushroo so deeply cherished. The idea initiated by Khushroo and fuelled by his Kazakh friends was to start India’s first and only professional full-time orchestra that would predominantly constitute Indian musicians. Thus, the Symphony Orchestra of India (SOI) came into being — which, today, has 16-18 full-time Indian members.

“It’s been quite a challenge — tougher than making water!” he quips, adding, “We had very few funds. Dr Bhabha was wonderful, he’d pull out his cheque book whenever we’d needed any money. We are reasonably connected, fortunately.”

“We have been rather successful, and people everywhere have been surprised at our quality. The choosing of the musicians and wanting to make it a complete orchestra of Indians was a big quest — but we will not compromise on quality,” he further states.

Khushroo, adamant on hiking the number of Indian musicians on board, has not only initiated a talent hunt but also instated a training programme at the NCPA. “I hope we have 40 by the time we retire. Our chance of survival is good. We have been invited to Germany and England in January 2019 for a tour, which will be six concerts, and we start our big season here in September — with collaborations with great music groups,” he lets on.

Regretful that starting up didn’t command as much dignity back when he started Bisleri as it does now, Khushroo is thrilled that his second great entrepreneurial stride has coincided with such an advantageous era in the Indian startup movement. “No matter where you are in life, dream big, don’t do routine work. If you’re good, the means will follow. Things really fall from the heavens when you’re the right person with the right intent. If you go through life’s humdrum and look back and think, 'what did I do?' you don’t want the answer to be, ‘I went to office every day,’” he says, before he takes my leave to rejoin his friends from the orchestra for yet another music-filled evening.