‘Obsess about the problem, not the solution’ – product tips from Richard Banfield, author, ‘Product Leadership’

Products and companies become successful if their teams focus relentlessly on understanding the customer’s problem. The solution will then emerge, according to this bestselling author.

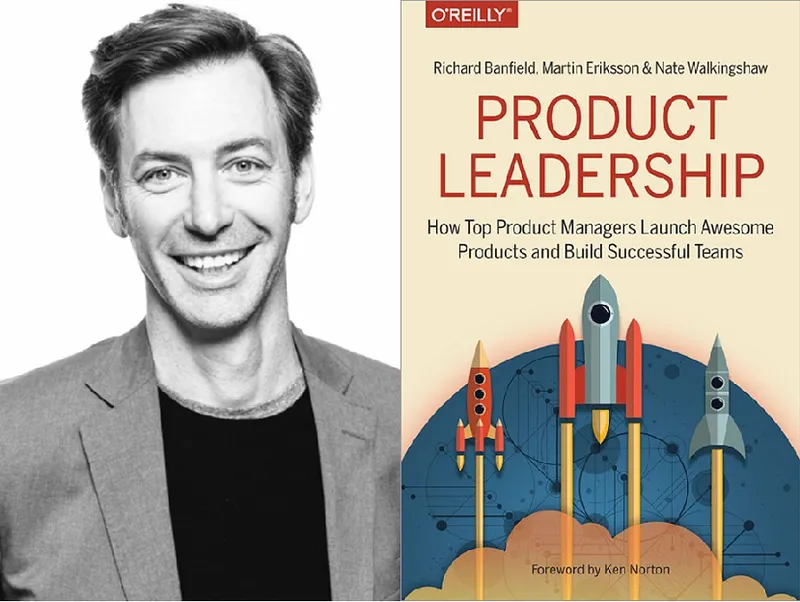

Richard Banfield is the CEO and Co-founder of Fresh Tilled Soil, a product strategy and experience design firm in Boston. He is the co-author of the bestseller Product Leadership: How Top Product Managers Launch Awesome Products and Build Successful Teams (see my book review here). His earlier books are Design Leadership and Design Sprint.

Richard joins us in this interview on product vision, team strategy, customer insights, co-creation, and capacity building.

YS: What are some ways for tech/business people without a design background to get up to speed on design literacy and competency?

RB: Read, watch videos, talk to designers, get a coach, attend a conference. But most of all, they should take on a small design project and get hands-on experience. A Design Sprint is a low-risk, discrete, and time-boxed way to do this. People learn fastest when they can get their hands dirty.

YS: How was your book received? What were some of the unusual responses and reactions you got?

RB: In general, very well. Over 12,000 copies sold in six months, Amazon bestseller in three categories. There were a few negative reviews. Mostly from those that wanted more depth. One negative review claimed the book was too focussed on the “absolute basics”, which was humorous because in our research we didn’t find any companies that were actually getting all the absolute basics right.

YS: In the time since your book was published, what are some notable new product insights you have come across?

RB: The complexities and challenges for teams to create a clear product vision and strategy. Most companies and their product teams still struggle with developing a product vision.

YS: How should product teams evaluate weak signals and anecdotal evidence which seem to contradict quantitative market trends?

RB: In general, we’ve heard that “the customer breaks the tie” is a reasonable way to weight quantitative evidence against qualitative feedback. This works if the data is macro or market data because each product potentially has a unique value proposition.

It becomes much harder to evaluate these things when the data is at the product level because the distinctions between features are almost useless and the customer’s behaviour is driven by irrational brand loyalty or emotions.

YS: What are the typical challenges product developers face as they spread across geographies and work in virtual teams?

RB: The biggest challenge of remote or distributed teams is the lack of opportunities to get to know each other. Rapport and strong bonds of trust are harder to form when teams are not co-located.

Our research showed this can be overcome by having leaders that invest significant time into helping members create these bonds. Practical applications of this are things like on-site meetings, daily video-conferences, mentoring relationships, and setting a powerful, motivating vision that unites the team.

YS: How should product teams strike that delicate balance between ‘stick to your vision’ and ‘adapt to a changed world’?

RB: A good product vision is timeless and separate from the underlying technology. It should be able to stand up to the test of time and be as relevant today as it was yesterday. Having said that, I am increasingly concerned that companies spend too much time developing their company vision and not enough time developing their product vision.

I am of the opinion that a company doesn’t need a vision. It just needs a problem worth solving to keep it focussed and aligned with why it should exist. However, without a clear product vision, which is a description of a future outcome not yet realised, the product organisation will be rudderless.

YS: Why is it that people confuse company vision and product vision, or are ignorant of this distinction?

RB: Not many companies have even thought this far through their vision development process, and hence there aren't many good examples of distinct company vision and product vision. Most companies are retrofitting their product solution to some marketing inspired vision. That’s backwards.

One company that is doing it correctly is PluralSight. They have a strong vision for each of their products and a guiding mission for their company.

YS: How should product teams strike that tough balance between ‘build on existing usage patterns’ and ‘let customers learn new ways to use this interface’? (for example, when the iPhone was first launched).

RB: This could probably be answered in a similar way to the qualitative versus quantitative argument — what does your customer care about? If new patterns make a big difference to how your customer perceives your value, then you should invest in those patterns. If the switching costs are high, or they simply don’t care enough, then adding “new and improved” features or patterns will be pointless.

Additionally, it is a very context-specific question. In highly technical environments, a challenging interface may actually serve the user’s needs for validation as an expert, while in broad-reaching consumer UI this could create the reverse outcome.

YS: What are your thoughts on developing ‘smart products,’ i.e. those that use AI, ML, IoT.

RB: Technology is great when it amplifies our human needs and makes us feel super-human. For example, there is a startup in NYC that uses ML to help crisis counsellors discover more insightful ways to help their patients identify the problem they are facing.

Technology for technology’s sake is harder to align with business needs because it is mostly a curiosity and has lower sustainable value.

YS: What product development techniques work well in the context of co-creation that involves two or more companies?

RB: Cross-functionality and pairing appear to have the highest value. In fact, any working structure that forces people to talk and get to know each other will increase their potential to produce a better product. Co-location is the best physical option but not always the most practical or cost-effective.

YS: It’s one thing to fail with a product, and a bigger dimension to fail with a company. How should founders regroup in these two situations?

RB: It depends on the company. If a company has been created with the explicit reason to support a product then product needs to come first in every major decision. Put another way, if your company exists because of the product, then product needs outweigh company needs.

If your company is just a holding structure for multiple products, then the overall portfolio needs to be accounted for. In these cases, a company may choose to let a product fail so that the overall structure can support the other interests in that portfolio.

YS: What are the top three success factors for academia and industry to work together and grow product development capabilities in society?

RB:

- Schools need to stop teaching knowledge and start teaching soft-skills like art, design, music, and human biology. Teaching facts is pointless. They need to help humans be better at relating to one another and being more empathetic towards each other.

- Create problem solvers, not factory workers (machines will do the grunt work).

- Immerse students in real-world situations through apprenticeships while they are still at school (not internships). This helps students get a better understanding of what careers look like, and helps them align their personal goals with company or industry goals.

YS: What is your next book going to be about?

RB: My current research is on understanding team dynamics and the effect they have on product delivery and quality. My next book is on highly effective teams and how they deliver value to the end user.

YS: What is your parting message to the innovators and aspiring entrepreneurs in our audience?

RB: Get out of your heads and your buildings so you can spend more time talking to customers.

Obsess about the problem, not the solution. You need to be able to understand the customer’s problem so well that the solution becomes blindingly obvious!