The Culture Code: how to cultivate the three group skills needed for organisational success

Bestselling author Daniel Coyle’s new book identifies three foundations for your company to succeed: build safety, share vulnerability, and establish purpose.

Drawing on a wide range of academic literature reviews and business leader interviews, the book The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups by Daniel Coyle shows how organisational culture built on the fabric of relationships can lead to phenomenal success. Daniel is the author of bestsellers The Talent Code, The Little Book of Talent, and The Secret Sauce.

“Group culture is one of the most powerful forces on the planet,” begins Daniel. “Culture is a set of living relationships working toward a shared goal. It’s not something you are. It’s something you do,” he explains.

Google, Pixar, Disney, IDEO and Navy SEALs are acknowledged as phenomenally effective organisations. Daniel unpacks some of their success by showing how they tap into the power of our social brains. Organisations excel not just because they have smart people, but because they work together in a smarter way.

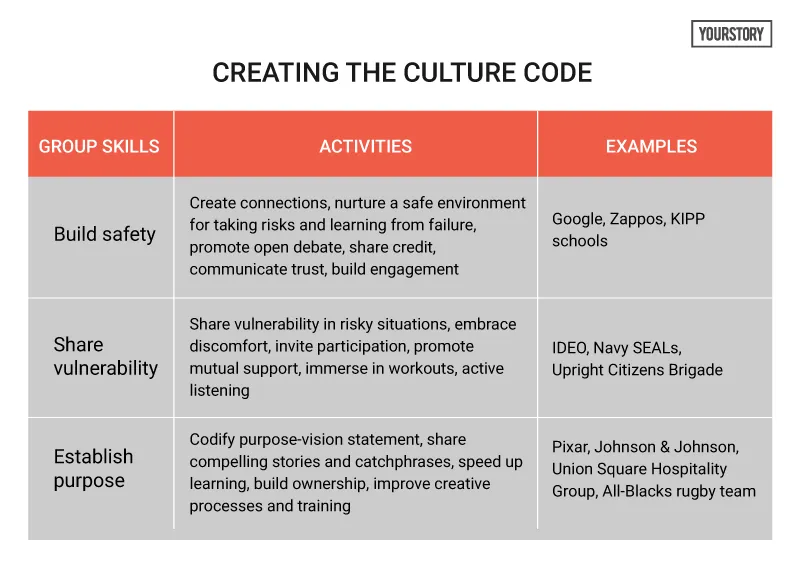

The three core skills are build safety (signals of connection to generate bonds of belonging and identity), share vulnerability (habits of mutual risk drive trust and cooperation), and establish purpose (narratives create shared goals and values).

The analysis is spread across 17 chapters and 280 pages, along with a list of recommended books such as Work Rules (Laszlo Rock), The Social Animal (David Brooks), Grit (Angela Duckworth), Teaming (Amy Edmondson), Switch (Chip and Dan Heath), Team of Teams (Stanley McChrystal), and Drive (Daniel Pink).

I have summarised the key messages in Table 1 below; each section of the book is highly readable and engaging, with a number of case studies and takeaways. See also my reviews of the related books Multiplier, Innovation Code and The Moonshot Effect.

In the real world, it is not just individual skills, experience or intelligence that matter for success, but group behaviour, interaction and collaboration. Simple activities like the Spaghetti-Marshmallow Challenge--an exercise in design collaboration--show that kindergarteners can outperform business school students by focusing more on experimentation than planning or status management.

1. Build safety

Safety is the foundation on which strong culture is built. Relationships in effective groups are described not just as friends, team or tribe, but family. Even the words used to describe colleagues have family-esque identifiers, eg. Googlers, Zapponians, KIPPsters. Bonds in such groups are almost addictive, and allow for vulnerability and risk taking.

Common ‘bad apple’ archetypes in organisations are ‘slackers’, ‘downers’ and ‘jerks’ who reduce collaborative energy. Effective leaders deal with this through warmth and positive energy, and repeatedly send out these messages: We are solidly connected, You are safe here, We share a future, We have high standards here, How can I help.

High-performing groups are characterised by high levels of mixing, good chemistry of interaction, communication across hierarchies, affirmations of trust, plentiful thank you’s across the board, short energetic exchanges, lots of questioning, and intense listening. Belonging cues such as eye contact, body language and mimicry ensure safe connection in such groups.

“Individuals aren’t really individuals. They’re more like musicians in a jazz quartet, forming a web of unconscious actions and reactions to complement the others in the group,” observes MIT professor Alex Pentland.

Companies like Google encourage free-wheeling debate irrespective of status or authority. The culture of challenge and contribution helped beat other players like Overture in the race to dominate Internet advertising. Such a culture creates lasting motivation. Research on Silicon Valley startups showed that the commitment model of hiring can be better than the star model or the professional model in startups.

Wipro improved retention rates in its Bengaluru call centre by focusing not just on company vision, star performers or generic merchandise, but on engaging new employees about their unique skills; they even received personalised sweatshirts. This psychological safety helped build connection, identity, motivation, and deeper engagement.

Rewards should be given not just to individuals but to groups and teams; this will encourage more collaboration and unselfish behaviours. Basketball coach Gregg Popovich is known not just for the gifts and restaurant bookings he does for his team, but for his “high-volume truth-telling.” He regularly asks players for input and ideas not just about the game but even about politics and social relationships. Connections are not just to each other but to things bigger than the game itself.

“One misconception about highly successful cultures is that they are happy, light-hearted places,” cautions Daniel. They are indeed energised and engaged, but the focus is on solving hard problems together.

This involves high-candour feedback, uncomfortable truth-telling, and confronting gaps and problems ahead. Standards are set high, and everyone is trusted, supported and expected to meet these standards.

Tony Hsieh sold one of his earlier startups to Microsoft (LinkExchange) and went on to found shoe retailer Zappos with the distinctive culture of “fun and weirdness.” He was inspired by TV shows like MacGyver, and had the belief that tough problems could be elegantly and creatively tackled.

Hsieh uses a method called collisions (serendipitous personal encounters) to drive creativity, community and cohesion. This amplifies the sense and scope of possibility both inside and outside the organisation. “When an idea becomes part of a language, it becomes part of the default way of thinking,” he explains.

Creative clusters are effective if there is close proximity between participants, This affects frequency and quality of communication. “Closeness helps create efficiencies of connection,” explains Daniel. It can transform strangers into a tribe. “Create spaces that maximise collisions,” he advises.

Other useful actions are giving thanks to everyone (chef Thomas Keller thanks dishwashers at restaurant openings), hire and fire painstakingly (“No Dickheads” at New Zealand All-Blacks rugby squad), give everyone a voice (Navy captain Michael Abrashoff asking each sailor for inputs about the ship), capitalise on threshold moments (employees’ first days at work), embrace fun, and even pick up the trash (sports coaches cleaning locker rooms).

A sense of humour is also important. “Laughter is not just laughter; it’s the most fundamental sign of safety and connection,” says Daniel.

2. Share vulnerability

“Exchanges of vulnerability, which we naturally tend to avoid, are the pathways through which trusting cooperation is built,” Daniel explains. Cooperation is a group muscle that is strengthened through risk taking and being vulnerable together. Trusting cooperation is the next step after building connections. This is not easy, and is often marked by tension, struggle and hard feelings.

Pixar’s BrainTrust meetings provide candid feedback at the early stages of movie development. Navy SEALs’ After Action Reviews (AAR) provide raw, painful feedback with lots of emotion and uncertainty; but this also leads to a “hive mind” and “unconscious genius” further down the road.

“These awkward, painful interactions generate the highly cohesive, trusting behaviour necessary for smooth cooperation,” says Daniel. Vulnerability is a sign of strength, not weakness.

“Vulnerability doesn’t come after trust – it precedes it. Leaping into the unknown, when done alongside others, causes the solid ground of trust to materialise beneath our feet,” he explains. For example, Steve Jobs would often begin conversations with the phrase, “Here’s a dopey idea.”

Leaders leverage vulnerability to send out messages like Anybody have any idea?, See if someone can poke holes in this, Tell me what you want and I’ll help you, I’m doing this crazy project and I need your help, You have a role here.

Comedy group Upright Citizens Brigade builds not just on speed and simplicity but on long and complex routines based on the Harold Method for “group brain workout.” It stresses excellence, teamwork, mutual support, trust, active listening, and avoiding judgement.

Success in effective groups comes from thousands of micro-events and small inter-personal leaps. Rank is switched off and humility is switched on. This helps create a shared mental model based on experiences and even mistakes.

Swedish engineer Harry Nyquist helped build cohesion at the legendary Bell Labs through his warmth, curiosity, and endless flow of ideas and questions; he was a polite, reserved and skilled listener. Such catalysts are “spark plugs,” says Daniel. IDEO’s Roshi Givechi is also a roving catalyst, involved in a number of projects and connecting people to new possibilities.

Such “gentle guidance” with lots of nudging, emotional signaling, and even choreography helps build connections and excitement, and “surface” new ideas and projects. “Listen like a trampoline,” Daniel advises; absorb what others say, listen to all they say, and add energy to the conversation.

“Make sure the leader is vulnerable first and often,” advises Daniel. Messages can be on the lines of I was scared, and It’s safe to tell the truth here. The tone is set right in critical moments like the first vulnerability and first disagreement.

Leaders should also over-communicate expectations, and encode the principles in the form of books given to all employees (eg. “Going out of your way to help others is the secret sauce” is a principle in the Little Book of IDEO).

Useful tools here are Before Action Review (intended results, anticipated challenges, earlier lessons, success factors), After Action Review (intended results, actual results, causes, same actions in future, different actions in future), and Red Teaming (alternative disruptive approaches).

“Embrace the discomfort. Aim for candour, but avoid brutal honesty,” Daniel urges. Pixar promotes debate but not at the cost of causing hurt or demoralisation. Reflection and critique may seem inefficient at times, but improve professional development and performance in the long run. Daniel also offers other leadership tips like flash mentoring and even disappearing for some time.

3. Establish purpose

From connection and cooperation, companies need to move on to commitment: purpose, vision and mission. Codifying a sense of purpose in a vision-mission statement, along with storytelling, can create a culture of collaboration. Leaders should get employees on the same page when it comes to questions of What are we about, What do we stand for, and Who comes first.

“Stories are the best invention ever created for delivering mental models that drive behaviour,” explains Daniel. Stories trigger cascades of perception and motivation. (See also my reviews of the related books People with Purpose and Storyteller’s Secret, and the tool YourStory Changemaker Story Canvas.)

Sticking to the company’s commitment to customers in its credo helped Johnson & Johnson successfully navigate the Tylenol poisoning crisis in 1982. The business eventually recovered by doing what was morally and ethically correct (calling for a nation-wide withdrawal of the pills, and committing to safer packaging).

Desired behaviours create almost flock-like coordination, and are nurtured through continuous communication of mottoes and catchphrases, as seen in organisations like New Zealand All-Blacks rugby team (Pressure is a Privilege, and It’s an honour, not a job) and KIPP schools (Prove the doubters wrong, and Be the constant, not the variable).

Techniques like mental contrasting help envision reachable goals and the obstacles along the way, which can trigger motivation and resolve. Setting noble goals creates more contribution, warmth, interactions and feedback in high-purpose organisations. A clear beacon of purpose can provide a magnetic field that aligns the organisational compass.

For example, Portuguese football organisers effectively dealt with English soccer hooligans by staying away from confrontation and focusing instead on cascading social cues of warmth and better behaviour.

“One of the best measures of any group’s culture is its learning velocity – how quickly it improves its performance of a new skill,” Daniel notes. This depends on the framing of the skill, intended impacts, and team roles, along with rehearsal, active reflection, and debate.

A simple, steady pulse of real-time signals is also effective in orienting the team to the task and to one another, and channeling attention to the larger goal. “What seems like repetition is, in fact, navigation,” he says.

Different approaches will be needed for consistency as compared to innovation, i.e. for proficiency in well-defined performance (eg. restaurants, where employees need to know exactly what to do and keep doing it consistently) as compared to creating something new in high-creativity environments (eg. movie studios, where people need to discover what to do). A lighthouse model and vivid memorable rules of thumb work in one case; an engineer approach to team dynamics and creative autonomy works in the other.

For example, restaurateur Danny Meyer promotes a sense of warmth and home ambience in his restaurants via principles like Read the guest, Athletic hospitality, Turning up the home dial, Creating raves for guests, and Making the charitable assumption. Other catchphrases are You can’t prevent mistakes, but you can solve problems graciously, and The road to success is paved with mistakes well-handled.

Union Square Hospitality Group’s Richard Coraine uses phrases like We are all paid to solve problems. Make sure to pick fun people to solve problems with, and Stone after stone to form a bridge.

Pixar has a stunning office building, but its co-founder Ed Catmull candidly admits it could have had wider hallways and bigger cafes. “All the movies are bad at first,” he adds. The creative focus is not just on brilliant breakthrough ideas but on having a systematic process to churn out lots of ideas and give candid feedback on them to unearth the right choices.

Experience can sometimes get in the way of hearing and accepting other points of view. Debate and discussion in a “safe, flat, high-candour environment” helps team see mistakes and move in the right direction.

Pixar University increases creativity and diversity by providing continuous learning across a wide range of disciplines. Pixar also invests in shorts that run before its feature films. These experiments transmit, amplify and celebrate the purpose of the whole group.

Catchphrases at Pixar include Hire people smarter than you, Listen to everyone’s ideas, and Fail early, fail often. After being acquired by Disney, Pixar’s Catmull created a common gathering place at Disney called Caffeine Patch, and handed over the responsibility of coming up with ideas to directors instead of studio executives. New behaviours and ways of working led the same people to produce a string of hit movies.

“Building creative purpose isn’t really about creativity. It’s building ownership, providing support, and aligning group energy towards the arduous, error-filled, ultimately fulfilling journey of making something new,” Daniel explains. Ultimately, the team journey is about trying, failing, reflecting, learning, and moving on.

The author ends his book by showing how he implemented the above three principles in his own stint as a writing coach for school students; he acted more as a guide on the side than a sage on the stage. He encouraged roundtable discussions by the students, shared thoughts on books and writing habits, had the students read essays aloud, and invited feedback from one another; he also set guidelines such as the VOW (voice, obstacles, wanting) elements of a story.

He encouraged the students to behave like “creative athletes,” and let some discussions wander off-target to gauge their passions and interests. As a result, the team performed well in tournaments and some students explored their creativity in new areas like theatre.

There are examples of small cohesive cultures all around us, the author signs off. Leaders should ultimately learn how to open up to their own shortcomings and create honest conversations.