How a Class X pass out built India’s largest mobile phone retail chain: the story of Rs 2,000 Cr Sangeetha Mobiles

In an extraordinary tale of brick-and-mortar entrepreneurship, Sangeetha Mobiles’ Subash Chandra overcame a difficult childhood and took his Bengaluru company to unprecedented heights. Here’s his inspiring story.

Subhash Chandra L, Managing Director, Sangeetha Mobiles

Bengaluru-based entrepreneur Subhash Chandra L comes across as well-educated and has a strikingly clear way of expressing his thoughts.

In displaying his business acumen, he has no trouble recalling specific dates, numbers, and financial figures from over two decades ago.

One might associate this with a fancy degree from an expensive, international university. However, Subhash is a Class-X pass out, and most of his real education happened while he was running a business.

Subash had a tough childhood. His mother passed away when Subash was just seven years old, and his father’s business was not doing well.

After completing Class X, Subhash quit his studies. He never went back to formal education and took over his father’s business. The name of the business was Sangeetha Mobiles.

Today, the name is synonymous with offline mobile phone retail in South India with almost 650 retail outlets across the country and a turnover of close to Rs 2,000 crore.

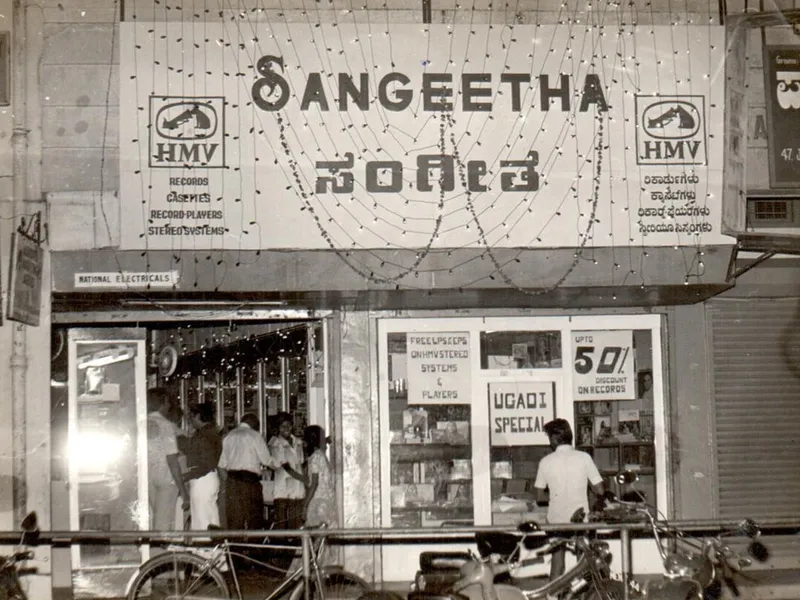

But back when it first started out, it was a tiny, 600sqft store on JC Road in Bengaluru selling home appliances and vinyl music records.

In an exclusive interview with SMBStory, Subash revisits his extraordinary tale of brick-and-mortar entrepreneurship, and how he built Sangeetha Mobiles into India’s largest mobile retail chain.

Sangeetha Mobiles' store in Kathriguppe, Bengaluru

A rough beginning

Subhash Chandra’s father, Narayan Reddy, was a farmer who went on to becoming a store manager for a home appliance store, Vijay Home Appliances, in Chennai. He was then transferred to Bengaluru.

But three months after the family moved, Subhash’s mother passed away.

At first, Narayan sent seven-year-old Subhash and his five-year-old sister to live with their grandparents in Nellore. When he turned eight, Subash returned to Bengaluru to stay with his father.

“By this time, in 1973, my father had started his own retail store for home appliances called The Merchant, in JC Road,” Subhash says. However, business did not pick up and The Merchant had to shut shop.

But Narayan’s father was not one to give up. He started another business to sell home appliances, and named it Sangeetha. He then converted one room of the store into a soundproofed area for selling vinyl album records.

“The store sold both home appliances and music records. The business was a partnership among three people, including my father, who had put in around Rs 20,000,” Subhash says.

The first Sangeetha store in JC Road, Bengaluru

But fate yielded the same result for Narayan. He made the mistake of investing too much on interiors and design and not enough on inventory. Sales floundered and Subhash’s father was again in trouble.

He thought of selling the store, but could find no buyers. One by one, his partners quit and Sangeetha became a proprietorship.

Times were hard for the father-son duo, who stayed at the store and ate meals from local eateries. But Subhash had the fire in him to scale his father’s business. He had helped around the store for a few years, and by 1982, the 16-year-old was determined to quit his studies and take over Sangeetha.

From home appliances to mobiles and SIM cards

“My father tried convincing me to stay in school as I was the topper in my class. But I still quit my studies and took charge of Sangeetha,” Subhash says.

Around this time, television sets entered the market. Sangeetha started retailing television sets and this proved to be a lifeline for Subhash’s drowning home appliances and music store. Subhash also started selling computers and pagers and transformed the business into a multi-appliance store for various electronic equipment.

In 1997, the turning point came when the first mobile handsets entered India. And Subhash was not one to let this new technology slip out of his hands.

“I knew right away that I wanted to sell these two-way communication devices. The first mobile phone I sold was a Sony handset costing Rs 35,000. In those days, that was a lot of money,” he says.

Radio sets in the first Sangeetha store

Subhash then cracked a deal with Spice Telecom and JT Mobiles and started retailing SIM cards. Signing up with Spice was another turning point because Sangeetha earned massive margins on selling SIM cards.

Back in the day, a prepaid SIM cost a whopping Rs 4,856. Of this, Sangeetha made a cool Rs 3,000 as commission on every card sold.

“The commission was so high because using a SIM card was expensive and this made it harder and more expensive to acquire new customers. Telecom providers charged customers Rs 16.80 per minute for incoming and outgoing calls, so getting customers onboard meant high acquisition costs,” he says.

Subhash pitched the idea of mobile phones and SIM cards to customers who came to Sangeetha to buy refrigerators, TVs, or other home appliances. From around 30 SIM cards a month, in next to no time, Sangeetha was selling around 1,900 SIM cards - all from the same store in JC Road.

Combating the grey market

Mobiles and SIM cards were becoming popular in India, but the grey market also grew. Customs duty made up around 60 percent of the cost of mobile phones made by Ericsson, Siemens, Sony, Philips, Nokia, and Motorola. Further, sales tax and turnover tax added to the cost.

On the other hand, people could buy smuggled phones in the grey market for half the price, since the price of smuggled phones did not include customs duty.

“People went to places like Burma Bazaar and bought mobile phones that were sold loose. A majority of phones sold in India in those early years were sold in the grey market,” he says.

To combat the popularity of the grey market, Subash decided to leverage the trust and faith he built with his long-standing customers who usually came to him for fans, iron boxes, TVs, etc. He also promised them their date of birth as the last few digits of the SIM card number.

Sales picked up, but there was still a long way to go. The grey market continued to dominate.

A view inside a Sangeetha store

Subhash decided to introduce a range of measures to increase his sales. He started selling phones with a bill and warranty and sold phones and SIM cards as single packages. Sangeetha was one of the first mobile retailers in the country to introduce these, he claims.

However, the entrepreneur realised customers didn’t want to buy expensive mobile phones from anyone, let alone Sangeetha, because theft was rampant in the city in those years.

On average, the mobile phones cost between Rs 10,000 and Rs 20,000 - a lot of money for those times. It was easy for burglars to swipe these devices from unsuspecting households since there was no tracking mechanism or security measures installed on the phones back then.

This was hurting Subhash’s business, but he responded swiftly. He was already offering insurance on the home appliances he sold, so he did the same for mobile phones.

Subhash then partnered with Standard Chartered to execute an EMI programme for mobile phones, making the payments even more pocket-friendly.

He seemed to have hit the nail on the head, and his mobile sales skyrocketed. Although customer sentiment towards the grey market did not dwindle by much, Sangeetha still saw first-time and repeat buyers come to the shop in hordes.

“I remember when I used to open the JC Road store at 9.30am every morning, I would see a long line of customers waiting for the shop to open,” he says.

Subhash’s suppliers and OEMs couldn’t believe their ears when he asked them for hundreds of units per month.

“They told me I was crazy because nobody could sell so many expensive mobile phones in a month. But my numbers showed I was doing it, and eventually I started procuring mobile phones in bulk,” he says.

Between 1997 and 2002, Sangeetha had captured 65 to 70 percent of the mobile phone market share in Bengaluru, Subhash says.

The CDMA era and onwards

By 2002, CDMA entered the picture. Pioneered by chip maker Qualcomm, CDMA was a second-generation telecommunications standard. However, GSM was already a dominant standard for 2G communications.

Several operators in India operated a GSM-based network. But Tata Tele and Reliance had gone one step further and had started operating a CDMA-based network.

Hutch also became a CDMA operator, and approached Subhash to open an exclusive Hutch store. He agreed, and although it was the work of Sangeetha, it was a Hutch store.

2002 was a landmark year for Subhash because he also decided to manufacture his own brand of mobile phones. The manufacturing happened in Taiwan and he sold the CDMA phones locally to Tata.

Subhash’s mobile brand was named Eurotel. However, GSM beat CDMA due to reasons such as lower royalty rates and wider market of carriers. Subhash had to shut Eurotel after a year and a half, and he lost a lot of money.

But the setback did little to dampen Sangeetha’s drive for conquering the market. He opened a second Bengaluru store, this time in CMH Road, Indiranagar, and also started expanding into the rest of Karnataka by opening stores in other cities.

By this time, mobile phone brands clearly noticed Sangeetha’s grip over the market in the State. They wanted Sangeetha to become their distributor, ie., sell to other retailers, many of which would be Sangeetha’s direct competitors.

“Many brands started to woo us and told us to move from retail to distribution. Till 2002, I was not interested in becoming a distributor for any brand. I was too busy handling retail,” Subhash says. He eventually gave in and became a distributor for Ericsson.

However, other retailers were not comfortable buying from a rival. Subhash then started a separate entity, Anu Distributors, only for distribution, and began selling to retailers. At one point, Anu was the biggest Micromax distributor in the country, and did Rs 1,000 crore worth business with the brand.

Meanwhile, Sangeetha expanded to Hyderabad and Chennai. Subhash also came up with more unique services such as insurance for liquid damage and physical damage. He partnered with London company EIP.com to provide over-the-counter claim settlements in 72 hours without the need of an FIR.

But eventually, Subhash realised the company was paying out too much money to keep the mandatory mobile insurance going.

“So, we made the insurance optional to cut back on the expenses,” he says.

The entrepreneur again decided to try his luck at launching a brand, but to no avail. The era of Indian mobile phones was ending and Chinese brands such as Xiaomi started flooding the market.

Sangeetha Mobiles staff

The ecommerce wave

Along with the influx of Chinese handsets came the ecommerce boom. It was a new chapter for Sangeetha Mobiles, as new entrants Flipkart and Amazon started eating into the company’s market share.

“Flipkart and Amazon caused bloodshed in the smartphone market with their heavy discounting. We could never match their pricing. Between 2014 and 2016, our turnover and bottomline dipped. For the first time in our history, we were going down,” Subhash recalls.

But he was not going to be outdone. Like he did before, Subhash pulled another rabbit out of the hat by coming up with a new scheme for combating heavy discounting by ecommerce players.

It was called the Price Drop Protection scheme.

After a customer purchased a smartphone from Sangeetha, the company would check if any ecommerce players sold the same model at a cheaper price in the next 30 days. If they found evidence of this, Sangeetha would contact the customer and refund the difference between the original amount paid and the new price on the ecommerce website.

“We did it to save ourselves for the time being. We ended up getting an extraordinary response, so we continued. The highest price drop we refunded was Rs 14,000 on a Sony Xperia model,” Subhash says.

The scheme helped Sangeetha stay afloat and retain its strong offline presence. Subhash also launched new schemes for damage protection and screen replacement. He bundled the one-year damage protection, liquid damage, price drop, and screen replacement schemes and offered it for Rs 499.

Even today, the bundle costs the same.

Further, Subhash was one of the first people Chinese online smartphone brands came to when they expanded their sales to the offline market.

Presently, Sangeetha has 4,000 employees: 2,250 on direct payroll, and the rest as promoters provided by smartphone brands.

Sangeetha sells smartphones from almost all brands, including Apple, OnePlus, Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo, Samsung, Realme, etc.

It sells around 7,000 models a day, and around two lakh each month. The retail chain also has a website where smartphones can be ordered.

“There is an impression that ecommerce websites sell at cheaper prices than us. However, this is not true, except on end-of-life models. But, other than that, considering all our schemes and pricing, Sangeetha can offer any smartphone model at a cheaper price than online,” Subhash says.

Sangeetha is a privately owned company and hasn’t yet accepted any offers from investment bankers. “We want to reach 1,000 stores before talking to investment bankers,” Subhash says.

An IPO is also in the pipeline, but only after Sangeetha reaches Rs 3,000 crore turnover. Subhash thinks this could be just two years away.

“It is not true that I have only tasted success. I moved between several product categories and always wanted to ride on the latest curve. I took a leap of faith in mobile phones and that proved lucky. My difficult childhood made me stronger and I slogged all my life to build the business. I gave my heart and soul for Sangeetha Mobiles,” he says.

(Edited by Evelyn Ratnakumar)