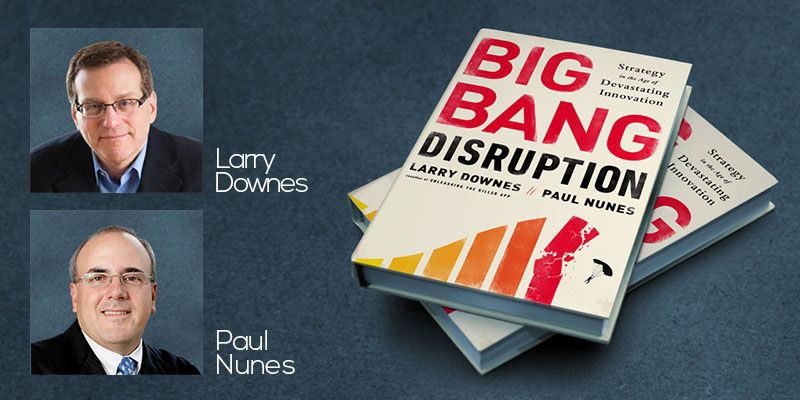

Youth are geared to handle and create disruptive innovations: authors Larry Downes and Paul Nunes

Larry Downes and Paul Nunes are co-authors of the bestseller Big Bang Disruption (see my book review). Downes is Research Fellow at the Accenture Institute for High Performance, where Nunes is managing director. They join us in this exclusive interview on platform strategies for innovation, ecosystems for disruptive technologies, the potential of youth as disruptive innovators and the value of collaboration with customers.

YS: How was your book received?A: We have had terrific reception so far, with both incumbents and entrepreneurs agreeing that the conclusions we draw from our research are compelling. We were delighted to see with both the original article and the book a number of blog posts applying the concepts of Big Bang Disruption to industry segments or specific geographies we had not yet considered. One article wondered what Big Bang Disruption would mean for the Canadian province of Prince Edward Island, for example!

YS: Some companies are resorting to platforms in addition to products as a way of surviving disruptors. What are the challenges facing such a platform strategy, and how long can such an approach last?

A: We have lots of examples of platforms, notably the smartphone / mobile broadband / app ecosystem, which are incubators for accelerating disruption. We also saw individual enterprises which used their existing networks and relationships to leverage one disruption after another, as for example Google, Facebook, and other information service providers have done.

Given the combinatorial power of component hardware and software, the challenge is always to balance the value of open platforms with the need to monetise innovation with some forms of control. The more open platforms, in other words, are the easier ones for innovators and innovations, but the platform developer and operator is not necessarily benefiting financially from those disruptors, reducing incentives to invest.

The other risk of a closed platform is that it cuts off the lifeblood of new ideas and new participants in the innovation process—notably customers, who we see especially in the early stages of Big Bang Disruption, as the most valuable collaborators an innovator can have.

YS: You note that Big Bang Disruptors are emerging more from within the US than outside – why is that so?

A: There are many factors that contribute to the continued US success in technology innovation, including momentum. Because US research universities, such as Stanford, MIT, and the University of Illinois, have such well-earned reputations for cutting edge development, they tend to attract the best-and-brightest students from all over the world in a kind of virtuous circle.

Beyond the basic research, there is both a physical and legal infrastructure that incentivizes innovation. That would include high-speed broadband networks on the one hand, and minimal restrictions on new businesses (what some call ‘permissionless innovation’) on the other. There are also more subtle incentives, including favourable tax treatment for long-term capital gains over ordinary income and the ability of institutional investors, such as pension funds, to invest in venture capital.

On the downside, however, restrictive US immigration policies and excessive patent protection are creating a drag on innovation. So too is the slow pace with which federal regulators are making available additional radio spectrum for mobile broadband, and the inefficiency and corruption of local governments that limits private investment in more cell towers and antennas. Many here in Silicon Valley are working hard to correct these counter-productive policies.

YS: You identify outsourcing as one strategy for a company to deal with the sudden exponential demand for a new product. But how should the outsourcing vendors themselves plan for withstanding such spikes in demand?

A: Those offering outsourcing services, including computing capacity as well as traditional manufacturing and assembly, need to operate on a portfolio model. In effect, the outsourcing vendors are arms merchants in competitive battles between the innovators. To maximize their effectiveness, they need to find ways to arm all the combatants at the same time.

Operational excellence—the ability to deliver high-levels of availability, security, quality control for production and raw materials—become critical buyer values. So uncompromising focus on these principles can become a competitive advantage in a world where buyers have visibility to a global market and components are more interchangeable. Labour cost advantages cannot win the day forever.

YS: What are some ways for innovators to protect their intellectual property while carrying out open innovation and crowdsourced partnerships?

A: One should first ask why innovators need to protect their intellectual property, or even whether they have any! Investors and entrepreneurs, as well as incumbents, often take too optimistic a view on what intellectual property they have, and what aspects of it truly need protection.

In the US, most patents issued today are worthless—they are so broad and so general that they would be unlikely to survive a genuine court challenge. Yet innovators fixate on them anyway. Given the increasingly short life-span of individual products and services in Big Bang markets, all the profit is going to be made in a relatively short period of time, long before patents and copyrights expire. Even a short lead over competitors can be sufficient, and far more valuable than the theoretical protection of IP, which has become prohibitively expensive both to secure and to enforce for all but the largest enterprises.

Meanwhile, the value of open innovation and crowdsourcing continues to increase at a dramatic pace. Why do you need to waste time and money to establish your IP, let alone protect it? What advantage does that really give you in practical terms? I am not saying it is never a good strategy to apply for patents and to enforce copyrights and trademarks, but at best that is only a hedge, and one that should not be pursued to the exclusion of actual innovating.

YS: What are the ‘politics’ of changing tack in a company and moving from an established product to creating a new one?

A: Change management continues to be a challenge for incumbent businesses, and the urgency of overcoming those challenges increases as disruptive innovation spreads across industries and the pace of change accelerates. In the book, we talk about the challenge for industries at the center of Big Bang Disruption, including consumer electronics, gaming and entertainment, and computing itself. Companies in these industries long ago learned of the need to cannibalize one generation of product in the interest of securing the market for the next generation, and have eliminated the sentiment around historic technologies that have nonetheless outlived their usefulness.

We were particularly inspired, for example, by the leadership of market leader Philips Lighting in announcing the retirement of incandescent light bulbs well in advance of the time when LEDs had achieved better and cheaper status. Philips saw where the technology was going and used that as its signal to change, rather than waiting for the inevitable when their flexibility would have been much less. So even industrial giants can do it.

YS: How should innovators strike that delicate balance between ‘Stick to your vision’ and ‘Adapt to a changed world’?

A: By widening as much as possible their communications with customers and other stakeholders through social media and other information tools. The first rule of Big Bang Disruption is to ‘Listen to the Truthtellers’. They will separate the reality of the market from wishful thinking every time.

YS: What do you see as some ways in which the health care sector will adapt to disruptive technologies, such as wearables?

A: I am not sure that health care will adapt to wearables at all. In some ways the health care industry in many geographies is so broken that consumers and innovators may end up creating a replacement driven by new technology rather than trying to force-fit those technologies onto the old infrastructure.

At least in the US, the culture of health care is very much driven by the assumption that only medical professionals can collect and interpret health information, as well as to diagnose conditions, determine treatments, and measure outcomes. But the model is so dependent on highly-trained individuals and a lack of standardization for any of those processes that it winds up limited to being a grossly inefficient solution for only a few wealthy patients and basically no service at all for everyone else.

Health care seems to have a natural resistance to any innovation that offers efficiency, standardization or automation, or which gives any role to the patient other than a purely passive one. It is hard to see how that culture is going to adapt to technologies that challenge each and every one of those assumptions.

YS: What is your outlook for the next generation of innovators who are growing up in a world of Big Bang Disruption?

A: It’s not clear that we need to give much advice to young people; it’s more likely the other way around. Much of what we learned about disruptive innovation, especially in mobile technologies, we learned from young entrepreneurs and their customers. They embody creativity, critical thinking, independence, experimentation, openness to change, and the value of collaboration.

Those ideals are far more valuable than the more mundane, but also important particular technical skills of programming, design, testing, customer service, and stakeholder management.

YS: How do you see exponential technologies impacting social entrepreneurship, eg. green technologies, eradication of disease/famine?

A: We see information technology as serving two critical roles in Big Bang Disruption. On the one hand, it is the most mature of the exponential technologies, having spent decades now getting better and cheaper on a predictable basis—the prediction of Moore’s Law—improving its price and performance by a factor of two every 12 to 18 months. As such, it is an enormous generator of new value and new opportunity in any product and service that can be improved by embedding computing—processors, sensors, displays, cameras, memory, communications, storage, etc.

As the size and energy requirements of IT fall along with the price, that becomes a much wider category. At this point pretty much anything can be improved by introducing some level of computing intelligence to it, down to the level of packaging, and that is what’s happening, spreading the impact of Big Bang Disruption to industries far afield from computing and electronics.

At the same time, the ecosystem created by those technologies are also the incubator for other exponential technologies, providing testbeds for design, funding, research, collaboration, and testing. So we see in fields as disparate as genetics, materials science, and energy the emergence of new exponential technologies, developed and accelerated by IT. There are many promising developments in sustainable materials and energy, in agriculture, and in health care that will apply both these new core technologies and the infrastructure of IT to build and deploy them.

YS: In the time since your book was published, what are some new examples you have come across of disruptors?

A: We find new examples every day! In January, we launched ‘Big Bang Disruption’ at the annual Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, and reported on several exciting new products and services we saw being demonstrated there. We wrote about them in a column for Forbes.com.

YS: What is your next book going to be about?

A: We have a lot of ideas but we haven’t committed to anything. What should it be about?

YS: What is your parting message to the startups and aspiring entrepreneurs in our audience?

A: If you are not prepared for ‘catastrophic success’, you will fail even worse by succeeding!