Cheating death - from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the Himalayas, Capt. MS Kohli's story

“I come from a place called Haripur,” says 84-year-old Captain Mohan Singh Kohli. A city known for the rich diversity of its fruits, Haripur is nestled in Hazara, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. In 1931, when Capt. Kohli was born, it was still called the North-West Frontier Province. Under the surface of Haripur, in its earthy veins, runs the water of the Indus. A hilly town surrounded by the Himalayan and Karakoram ranges, amongst the residents of Haripur are the descendants of Greek soldiers who stayed behind after Alexander’s conquest of the region in 327 BC. Modern-day Haripur though, was founded by General Hari Singh Nalwa in the 19th century, under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, second Nizam of Hazara. “My forefathers,” says Captain Kohli, “were killed on top of the mountain facing Haripur. And that place had become a place of pilgrimage for my family. As a child of seven-and-a-half, I would cross Indus’s tributaries to reach the top of this mountain, and never stopped till I was 16.” For those unfamiliar with the chronicles of yesteryears, a more current reference to Haripur would be that it was Osama bin Laden’s temporary home in 2004, before he moved to Abbotabad, only 35 km south of the city. “It’s surrounded by mountains on all sides. In fifteen minutes, you can disappear behind one hill and then another and then another. I was in Haripur in 2004, but I never met Osama,” he says with a chuckle.

Captain Kohli’s stay in his home was temporary, though -it would only last 16 years until the Partition. “Many people have left their home towns in Pakistan. Many have forgotten; many remember little. But my attachment to Haripur is so great, because I owe my whole life’s achievements to Haripur.”

In 1947, when Captain Kohli was only 16, riots shook Haripur. The Muslim League had become stronger, and so had the demand for Pakistan. The subcontinent saw an increasing number of mutinies. “A lot of people were killed everyday. We were students, and there was a big agitation in our family – whether to run away immediately or finish my matriculation examination.” Captain Kohli managed to finish his education in March. For three months he moved to India to search for a job. “I went to nearly 500 factories and shops searching for jobs. Everyone said, ‘No, sorry, we can’t.’” At the zenith of his exasperation, a radio broadcast on AIR on 2nd June announced that Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Jawahar Lal Nehru and Sardar Baldev Singh had proclaimed the partition of India. Captain Kohli and his father, Sardar Sujan Singh Kohli, returned to Haripur. By now, Captain Kohli’s results had come out – 600 on 750. He had topped the district. As a new country was being born, a new future was making way for itself for a young, adventurous man. He had been accepted into the prestigious Government College Lahore (now, Government College University, Lahore). “That happiness lasted only one week.” Suddenly people from other villages attacked Haripur with no provocation. Once, Alexander the Great had burnt this civilisation to ashes and left its residents for dead. The people of Haripur would relive that pain millennia later at the hands of their own. “We ran from one rooftop to another. The whole night we just hopped terraces until we reached the police station. People were being killed on the spot; their heads were hung outside their houses.” Captain Kohli and his father were taken to one camp after another until they reached Panja Sahib, a holy shrine for Sikhs, in Hasan Abdal. After spending a month there, they were taken to India in an open goods train, stuffed in a wagon burdened by hundreds of refugees. “We were attacked by the local police. Out of 3,000 people in the train, some 1,000 were killed in cold blood.” Cutting through the bloody chaos, a train carrying the Baloch regiment screeched to a halt, and out of this train came marching Mohammad Ayub Khan, freshly minted into the new Pakistan Army.

As fate would have it, before Ayub Khan became President of Pakistan, he had a humble beginning in Haripur as a neighbour to the Kohlis. On recognising him, Sardar Sujan Singh had screamed: “Ayub! Save us!” Khan, Captain Kohli remembers, responded: “Don’t worry, Sujan Singh. I have come.” The man who would, in a decade, take over the entire nation of Pakistan in a coup, gave safe passage to the Kohlis to Gujranwala, where they survived more attacks, until, in the middle of October, they reached Delhi. “We picked up the threads of life, and started life all over again – without a penny in the pocket, with torn clothes and barefooted.”

“I have been to Haripur six times,” says Captain Kohli. The last time I was a guest of Ayub Khan’s son, and I went to his memorial to pay my homage. I said to him, ‘You had saved my life. This is my last visit to Haripur.’”

Even today, Haripur greets Captain Kohli with fondness and love. “I think the people of the villages feel that India and Pakistan should have stayed together. It’s the politicians who create agitation,” he says. Though it’s been more than half a century since he bid his home farewell, the home of Himavat, Captain Kohli’s greatest attachment, still runs through the crown of India, Pakistan and Nepal. When he joined the Indian Navy, his superiors told him he could go once in two years to any place in India he declared his home town. “I declared Pahalgam in Kashmir my home town, and I went there in 1955.” The Himalayas were back in his life. More than 12,000 ft in the skies, Captain Kohli decided to visit the ancient Amarnath Cave. In a suit, tie and devoid of woollen clothes, a daring navy man reached the shrine unscathed. “I became a mountaineer.”

For Captain Kohli, there was no looking back. In 1956, he conquered Nanda Kot. At 17,287 ft, the allure of seizing a formidable peak against murderous winds storming through the mountain’s ancient cracks, clefts and chasms had an almost mystical charm in the ‘50s. For the first few men who saw the world from the home of the Gods, it was history in the making -a death-defying endeavour.

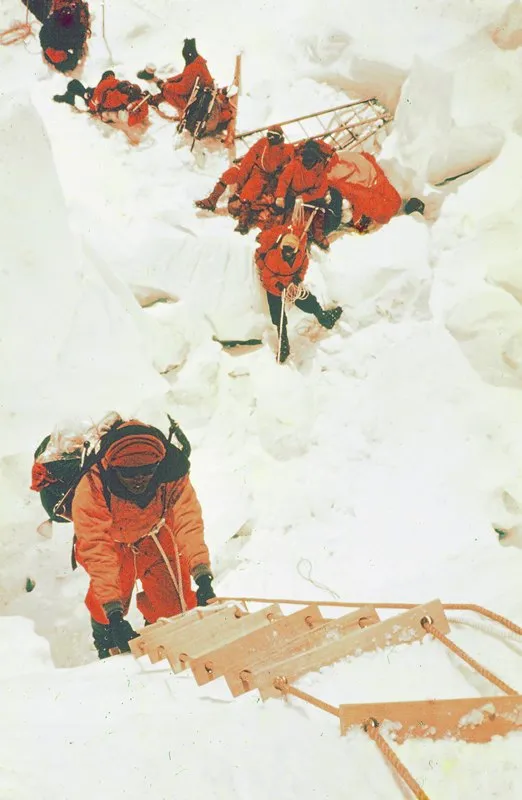

Histories are not written by the deeds of dangerously brave men any more in the same way wars are not fought by unnerving generals. Nothing exemplifies what it meant to trek -when men made names trailing mountains- than Captain Kohli’s experience on Annapurna III in 1963. “We were looted by the locals, two members were taken hostage, but finally we came back.” After surviving a handful of expeditions, Captain Kohli felt he was ready for the Everest, the highest, youngest and equally rebellious peak.

Before the successful expedition of 1965, Captain Kohli had missed reaching the peak twice – once by 200 metres, and another time by 100 metres in 1962. At one point, after losing communication with other camps in a terrifying blizzard, his team was declared dead. Until they returned a full five days later.

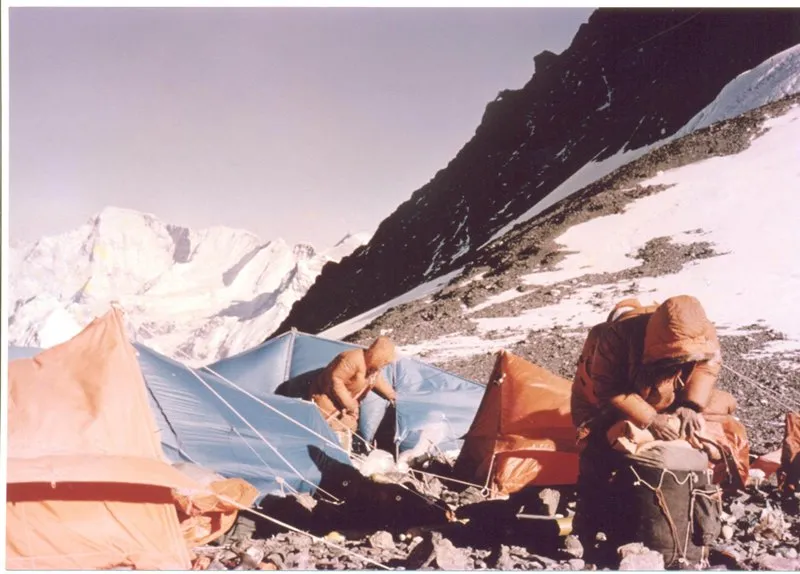

Finally, in 1965, Captain Kohli led what would be a historical expedition to the Everest. It would make India the fourth country to conquer this most revered of peaks for mountaineers. “We had 800 porters and 50 sherpas. We put nine people on the summit, and set a world record.” In the last five years, no successful attempt to the Everest had been made by India. Ang Tshering, previously part of the 1963 American expedition, headed the sherpas. Perhaps, the Gods themselves had not fated Captain Kohli to reach the summit until that fateful day in 1965 with 25 tonnes of equipment painfully brought together from various cities across India. “This team achieved so much success only because of its spirit. Everyone deserved full credit. When the Government of India announced Arjuna awards to us, we declined. Either they had to give it to the whole team or no one.”

These days, the only people who acknowledge your arrival from the Everest are your family and friends. There was a time when sinking the flag of your nation was a moment for the books. “We were met by mobs at the airport. I was asked to address both the houses of the Parliament.” Captain Kohli’s 1965 expedition put the then oldest person on Everest – Sonam Gyatso (42) – and the youngest one, too – Sonam Wangyal (23). For sherpa Nawang Gombu, it was the second time meeting this enticing peak. From 25th February to the end of May, the journey went on for three harrowing months.

Captain MS Kohli, Lt. Col. N. Kumar, Gurdial Sigh, Capt. A. S. Cheema, C. P. Vohra, Dawa Norbu I, Hav. Balakrishnan, Lt. B. N. Rana, Ang Tshering, Phu Dorji, General Thondup, Dhanu, Dr D. V. Telang, Capt. A. K. Chakravarti, Major H. P. S. Ahluwalia, Sonam Wangyal, Sonam Gyatso, Captain J. C. Joshi, Nawang Gombu, Ang Kami, Major B. P. Singh, G. S. Bhangu, Lt. B. N. Rana, Major H. V. Bahuguna and H. C. S. Rawat had made history.

“I promoted trekking in the Himalayas extensively.” However, within a few decades, Captain Kohli was told his over-enthusiasm in promoting the range had a not so happy ending. “The Himalayas are flooded with garbage today. There is degradation, forest cover has almost halved and most of these mountains are full of dead bodies. I felt guilty.”

With unprecedented commercialisation, the Himalayas, now more than ever, has become nothing more than a tourist destination. “To save the Himalayas,” says Captain Kohli, “I contacted Late Sir Edmund Hillary, Herzog, Junko and many others who’ve been part of the Himalayan journey.” Together, they formed the Himalayan Environment Trust to save the peaks from further destruction. “In those years, very few expeditions happened. Now you have some 30-odd expeditions before and after monsoon. It has become about money, and you can see people standing in a queue to reach the Himalayas. Even if you’re not physically fit, you can pay some 20-25 lakhs to go there, get sherpas, get equipment and make the journey,” opines the mountaineer.

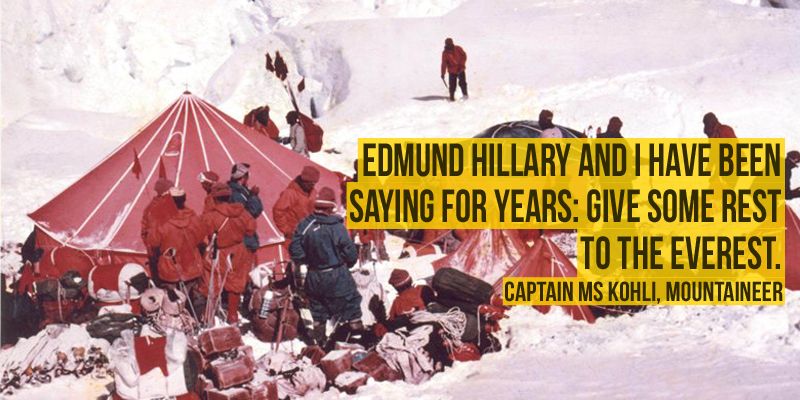

“With all these conditions at Mt Everest, Edmund Hillary and I have been saying for years: give some rest to the Everest. But money is money for the poor countries. They think we’re barking. Therefore, the problem has become acute. You can’t help it.”

It’s traumatic for Captain Kohli to see the Himalayas forced into this malformation. It was once both a serene and violent place that made him face death 18 times. “We didn’t feel scared then, because once you go into the high mountains, you feel you’re touching the sky. You feel that you are near to God; you’re cut off from the materialistic world.”

“In 1962,” Captain Kohli remembers, “We read our final prayers three times, and we were looking for our permanent graves. But nobody worries; we take it as part of life, because when you go to such high mountains, you become part of the sublime force.”

His own grandson tries to persuade him into letting him go to the Everest. However, the mountaineer has his reservations. “I said if you want to go, go in the proper way. There are five mountaineering institutes in India. Go for the courses, and when you find time, go for at least one expedition. Do advanced courses, and then go to the Everest.”

Captain Kohli concludes, “I’m absolutely convinced that no nation without the instinct for adventure can rise up in the world. So if the nations want to achieve big and become great, instinct for adventure among young people is very important. People who are initiated into adventure, they go from one place to another, trekking, white water rafting, or climbing. It’s perpetual. But people who are not initiated, they’ll keep on feeling we’re are bad and it’s a stupid thing to do. My advice to the nation is to send our school children into the Himalayas on excursions. Once initiated into adventure, their lives will change.”