When women revived their pastures in rural Rajasthan

It also became a fight for the women against years of suppression, to bring about societal transformation.

When Kesi Bai became the Sarpanch of Chitamba panchayat in Bhilwara district, fortunately the going was not as tough as it is presumed to be for women in Rajasthan. She had support of her people, and even if was not unanimous she made an efficient use of it.

The first decision that Kesi Bai took was to revive the pasture land of her village Sanjadi Ka Badiya to ensure that everybody gets enough fodder and fuelwood from local sources.

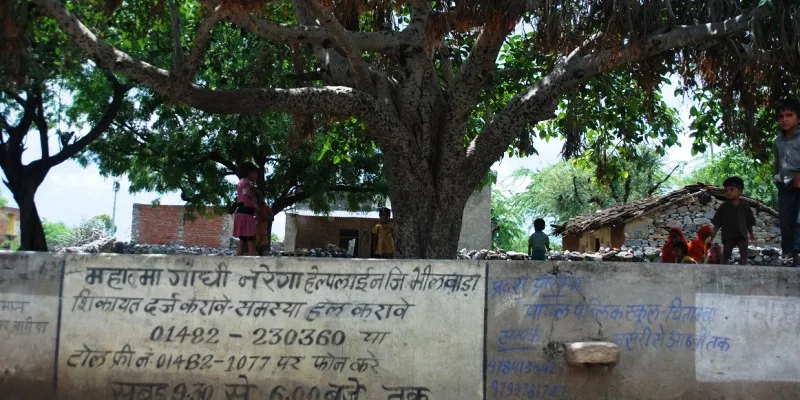

Reviving the pasture that had been degraded over years because of wood cutting and drought involved discussion and meetings with the village elders and that is where the symbolic transformation of women's status happened. Most discussions and decisions in villages in this part of Rajasthan happen at Hatai, a raised platform around a tree in the centre of the village where all men sit when a meeting is called. Traditionally, women and lower caste people are not allowed to sit at the Hatai. In some villages, if a meeting is going on, women have to carry their slippers on head while crossing the place as a mark of respect.

When discussions regarding the pasture land started in Sanjadi Ka Badiya, women decided to sit on the Hatai along with men. "This may seem a trivial matter but for women suppressed for ages, this was a victory of sorts. Initially, they were scared of the village elders, but gradually they gained confidence," says the lean-framed Kesi Bai sporting a confident smile. Pyaraba, who played a major role in convincing other men of the village, narrates how he used to argue with them. "I would ask them that if Kesi Bai can unfurl the national flag on Independence Day at Chitamba as a sarpanch, why can't we honour all women here? Also, all women are like our mothers and should be allowed to sit on the Hatai,” he recalls.

Sanjadi has a huge common pasture of 75 hectare, but its degradation had resulted in trouble for the village, which mainly depended on animal husbandry. In the dry season, people of the lower caste would migrate to Malwa region in Madhya Pradesh to sustain their animals since they had little land to grow fodder. The denigration of grazing land also meant reduction of the water table, which in turn had a bad impact on whatever little people used to grow in fields. The women decided to make this work. They formed an all-women 'Charagah Samiti' and approached a team of the National Tree Growers' Co-operative Society (NTGCS) that was working on rejuvenation of pastures in nearby villages.

“We asked them for financial and technical assistance to develop our grazing land and make water harvesting structures," says Kesi Bai. That was in 1998. The women's committee started working as per the guidance of the NTGCS team and dug trenches, contour-bunds for water conservation in the pasture and planted trees and grass. All the work done was accounted and paid for. The payment for each day's work took place at the Hatai.

"The work was distributed by Gopinath, who was the 'mate' (incharge) for the work in the pastures but he would often come late. So we developed indigenous techniques like a rope with knots and wooden sticks to serve as a measuring scale for determining contour size. We also engaged young educated girls to do accounts, and payments were made accordingly," informs Sahiri Bai, who is also a member of the women's committee.

When the work began, the NTGCS paid the salary for a guard to protect the pasture trees but soon the women decided to do the work themselves. Every woman has to protect the trees by turn. The woman returning from the pasture after patrolling would place the baton in front of another woman's house indicating that it’s her turn the next day. "If somebody can't go, they exchange turns or pay somebody else to take care of their duty," informs Sahiri Bai. After 14 years now, the entire village sources its fuelwood from the pasture. The gazing requirement of at least four months is also met by letting the animals run loose in the pasture. The migration to Malwa has stopped and the grass production has gone up from 1.1 tonne per ha to two tonne.

When the natural resources were restored, the confidence to bring about other social changes also followed. Girls started going to school for the first time. The women also raised voice against the social custom of spending huge amount of money on death ceremonies. Earlier, it was customary to make sweet out of 10 sacks (500 kilos) of sugar when somebody died and at least one kilo of 'post' (cannabis) was consumed in the 12 days following a death. A kilo of cannabis costs at least Rs 60,000. So a poor family often had to take a loan to fulfill these social obligations. “We asked people to bring down this cost and now not more than 2-3 sacks of sugar are brought in and less people are invited for death feasts. Cannabis has been completely done away with," claims Kesi Bai.

The women did face resistance from the high castes though. The Thakur family, which used to head the village in earlier times, raised objections to the work done. "The brother who worked in the settlement office at Chitamba alleged forging of accounts claiming that the work done in the pasture was less than the amount paid for. We challenged him to get the work audited and it turned out that the work done was more than the amount paid for. Since then, he hasn't shown his face in the village," informs Pyaraba.

Disclaimer: This article, authored by Ravleen Kaur, was first published in GOI Monitor.