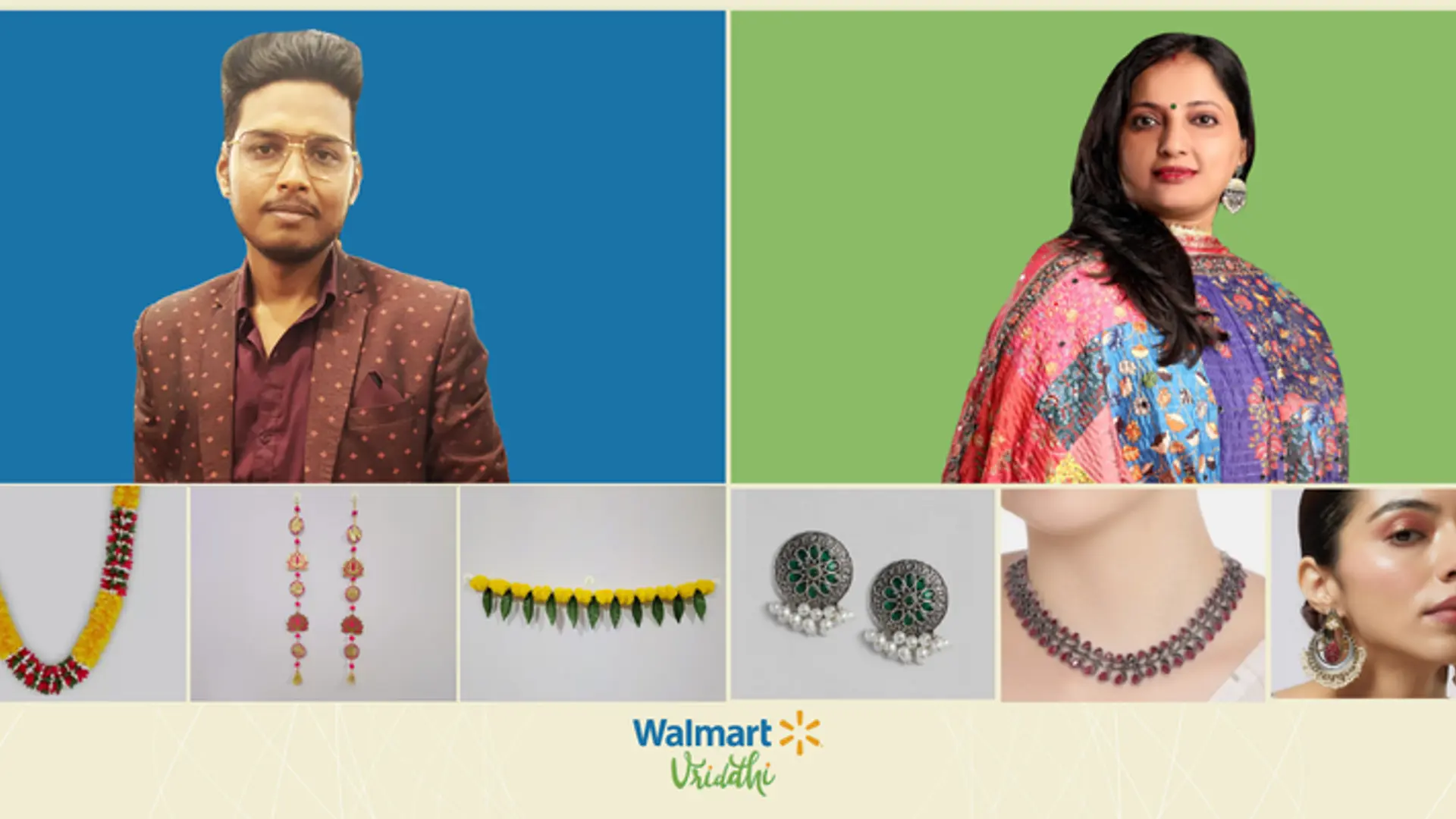

[Book Review] The Entrepreneurial Instinct: How Everyone has the Innate Ability to Start a Successful Small Business

by Monica Mehta2013 McGraw-Hill (Amazon)

15 chapters, 207 pages

Even without special degrees, sophisticated planning or access to venture capital, aspiring entrepreneurs can succeed if they have or cultivate the right mindset, habits, personality traits and instincts, according to author and investor Monica Mehta.

This book joins others such as “Lean Startup” by Eric Ries (see my earlier book review) on entrepreneurial risk-taking and decision-making, but with a stronger focus on medical research and personality implications.

The writing style is straightforward and direct, with numerous sidebars summarising key takeaways; but the references section could have been more solid, and with annotations.

Monica Mehta is an investor, author and expert on small business and finance topics. With 15 years of experience in the industry, she is currently a managing principal at Seventh Capital, a New York based investment firm. She also writes a regular small business column for Bloomberg Businessweek and appears on ABC News and MSNBC. She is a graduate of the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and can be followed on Twitter at @MonicaMehtaNYC.This book brings together research on entrepreneurship as well as findings from medical science – in particular, brain chemistry, neuroscience and behavioural psychology. Some of the cited books include David Linden’s “The Compass of Pleasure: How our Brains Make Fatty Foods, Orgasm, Exercise, Marijuana, Generosity, Vodka, Learning and Gambling Feel So Good” and Richard Peterson’s “Inside the Investor’s Brain.” Cited journals are Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Featured case profiles include CLIF Bar, Marquis Jet, Skip Hop, Dogfish Head Beer, KIPP Charter School, J Brand Jeans, T3 Media, writers of Grey's Anatomy, and rock journalist Neil Strauss. The author’s own parents, who migrated to the US from India, are also the opening profile of the book; they started off selling Indian handicrafts, and now own a chain of apparel stores, a garment wholesaling company and an investment firm.

Not all entrepreneurs take classes, write business plans, and map out responses to every contingency. Interestingly, entrepreneurs have emerged even from problems like dyslexia and attention deficit disorders (Ingvar Kamprad, IKEA; David Neeleman, JetBlue Airways; Charles Schwab, Schwab Corporation). Others bucked convention and successes out of necessity, ignorance and sheer stubbornness.

Many successful entrepreneurs were college dropouts: Tom Monaghan (Domino’s Pizza), Richard Branson (Virgin group). Several other successful entrepreneurs did not do core market research: Howard Schulz (Starbucks). Many successful entrepreneurs did not have any training or experience in their lines of business: Anita Roddick (Body Shop). Several entrepreneurial and creative people went through a string of failures and rejections before succeeding: Henry Ford, Walt Disney, Charles Schultz, Dr Seuss, and even Vincent van Gogh.

To take the journey, put action over planning. To fund the journey, put planning over action

Mehta stresses over and over again.

It is important for entrepreneurs to plunge in and take action in the beginning, measure the outcomes and make necessary adjustments. Business plans are not of much use when the initial offerings and steps will be continually refined and tested. Only after some stability or patterns have emerged and if financing is needed for scale, will it be necessary to develop a detailed business plan.

Entrepreneurship is not alchemy, but at the same time is not rigidly structured. There are frameworks for assessing customer needs and aspirations, learning from marketplaces and competitors, and taking calculated risks. Entrepreneurs have tapped traits and habits that allow them to take rewarding risks, overcome fear and failure, and thrive in the face of ambiguity.

Impulsivity and adaptability are two key traits of successful entrepreneurs, according to Mehta; entrepreneurs have an itch to try something new, and have the flexibility to roll with the punches and improvise. Entrepreneurs take smart rewarding risks, and overcome their fears and inhibitions. They know there is a time for planning and a time for action.

Medical tests have shown that entrepreneurs score higher ratings on questions that tested impulsiveness and measured cognitive flexibility (the ability to switch a behavioural response depending on a situation’s context). Risk-taking and direct action releases the chemical dopamine in entrepreneurs, and they feel more rewarded by it. But for most people, the pre-frontal cortex dominates, it is responsible for rational decision making rather than emotional action. “Dopamine provides pleasure, focus and motivation that drive us to do many of the activities necessary for our survival,” explains Mehta.

Entrepreneurs, astronauts, star athletes and commandos fall in one category of professions that call for impulsivity; those in more rational and structured professions include managers, professors, economists and software analysts.

Entrepreneurs have a can-do attitude, a belief that over time they will figure it all out and stop worrying. They are extraverts (optimistic, confident, reward-oriented), and open (with a high propensity for self-change and solving problems); they are flexible and not too conscientious. Successful entrepreneurs have stamina, grit, optimism, a sense of faith, and sometimes even the power of spirituality or religiousness.

Restlessness and unpredictability – along with starting off small and adaptively – helped Sam Calagione set up his successful Dogfish Head Craft Brewery. Andrew Ullman and Hayward Majors quit a finance/MBA track to start college search site CollegeSolved.com; they trusted their own instincts since no one in their inner circle had advice or “experience with the leap of faith that comes with entrepreneurship.”

“There are three types of people in this world: those who see the glass as half-empty, those who see the glass as half-full, and those focused on getting their glasses to the sink so they can fill it up,” Mehta succinctly describes.

“To live in fear of failure is to not live,” she admonishes. For the entrepreneur, impulsivity throws new things their way; adaptability turns these things into opportunities.

For those who want to become more entrepreneurial, they need to identify and overcome their own fears, which can eventually happen through small steps and proper conditioning – or even accidentally, through unexpected exposure to a new environment or discovery of hidden skills or new opportunities. Table 1 summarises some of Mehta’s recommendations for people to cultivate reward-oriented risk-taking behaviours.

Table 1: How to Take Reward-Oriented Risks

There are many sources for inspiration to become an entrepreneur: in what you do well, in the world around you, and even from grunt work and trash! This has led to the rise of ‘mompreneurs’ and even the birth of companies like American Refuse, founded by Tom Fatjo when his neighbourhood was faced with trash disposal problems.

“Both the optimist and the pessimist can be a good inventor. The optimist invents the airplane, while the pessimist invents the parachute,” according to business professor Saras Sarasvathy. Accomplished entrepreneurs are brilliant improvisers, her research shows. She asks: “If Mark Zuckerberg had conducted a feasibility analysis before writing code, do you think we would have Facebook today?”

For launching a business, Mehta cautions that too much pre-planning may actually hinder creativity and innovation or discovering unanticipated opportunities, as the case of HP’s early years illustrates (they even tinkered with an automatic urinal flush!). “The early days of a startup are more creative than analytical,” Mehta observes.

“Entrepreneurs who prepare themselves for the unknown would be better off drawing on the experiences of those in creative fields,” she advises. For example, jazz musicians in the midst of an improvisation selectively deactivate a portion of their pre-frontal cortex; the focus is more on ‘self-initiated’ thoughts and behaviour.

“One of our classic assumptions is that we learn more from failure than from success. Research contradicts this idea, though. Not only do we learn more from success than failure, but success breeds subsequent success,” argues Mehta. The cumulative and repetitive reward principle drives more learning than failure lessons, and that should be the driver of the productivity cycle: develop a sense of vision, roll out a beta, set short-term goals, and start the sales process.

Instinct-driven execution is about quickly finding out how right or wrong you were in your initial offerings and assumptions. Spot maverick customers, make them feel wanted, bring them on as advisors, make agile pitches, and build a good enough product (not a perfect product in beta), Mehta advises. The concluding chapters offer advice on financial planning, and the material is similar to that found in other books about startups.

“Entrepreneurship is contagious,” Mehta advises. “Surround yourself with people who have taken entrepreneurial risks. Most large cities offer business meet-ups and other networking events where like minds can gather,” she adds.

The book is filled with many inspiring quotes; it would be apt to end this review with a sample of them:

“Follow your bliss and don’t be afraid. Doors will appear where there once were walls.” – Joseph Campbell

“Rebelliousness can be healthy if well-directed.” – Sam Calagione

“Genius is nothing more nor less than childhood recovered at will.” – Charles Baudelaire

“Opportunity comes from the unknown.” – Michael Diamant

“Improvisational comedy is skydiving with your mind.” – Chris Griggs

“Desire can be a big unfair advantage for an entrepreneur.” – Jim McIngvale

[Follow YourStory's research director Madanmohan Rao on Twitter ]

![[Book Review] The Entrepreneurial Instinct: How Everyone has the Innate Ability to Start a Successful Small Business](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/wordpress/2012/12/monica-mehta-seventh-capital1.jpg?mode=crop&crop=faces&ar=16%3A9&format=auto&w=1920&q=75)