NASA may have just found life on Mars!

NASA’s “leopard-spotted” Martian rock may be the clearest potential sign of ancient microbial life yet—proof awaits sample return to Earth. Curious about whether we’re alone in the universe? This discovery could be one giant leap closer to the answer.

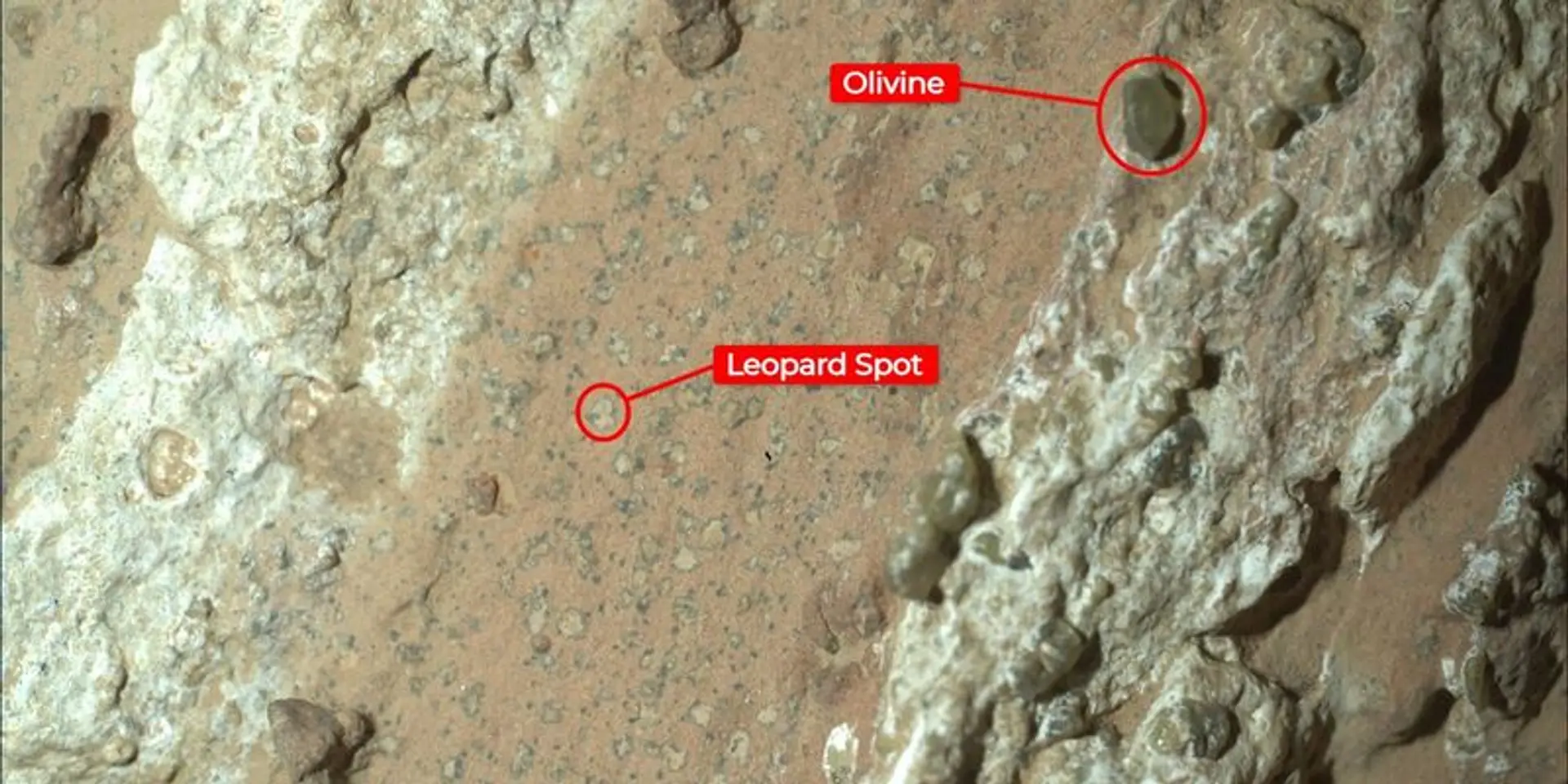

If you’ve ever wondered whether we’re alone in the universe, a speckled Martian rock is now center stage in that cosmic mystery. NASA’s Perseverance rover has found “leopard-spotted” textures and unusual mineral combos inside a 3.2–3.8-billion-year-old mudstone in Jezero Crater—features scientists say are potential biosignatures: chemical or textural clues that might be made by ancient microbes, but still need rigorous confirmation.

What exactly did Perseverance find?

In July 2024, the rover drilled a sample nicknamed Sapphire Canyon from a light-toned outcrop called Cheyava Falls within the Bright Angel formation—an ancient river channel (Neretva Vallis) that once fed Jezero’s lake. The team spotted ring-shaped “leopard spots” and dark nodules, then mapped their chemistry with instruments on the rover. The mineral fingerprints point to vivianite (an iron-phosphate) and greigite (an iron sulfide)—pairs that, on Earth, frequently form when microbes feast on organic matter in oxygen-poor, muddy environments.

A companion Nature paper adds the lab-grade detail: Perseverance’s SHERLOC instrument detected an organic Raman “G-band” (~1600 cm⁻¹) in Bright Angel targets (including Cheyava Falls), while PIXL and WATSON imaging tied those organics to iron-phosphate and iron-sulfide textures at sub-millimeter scales. In plain speak: mud + organics + specific iron minerals, all arranged in ways that look eerily similar to microbe-mediated reactions in Earth sediments.

Why scientists are excited—but careful

On Earth, vivianite and greigite commonly show up where microbes are busily recycling carbon in river deltas, lake beds, and coastal muds. That’s why this Martian combo raises eyebrows. Still, geology can be a gifted mimic: slow, non-biological processes can make similar minerals and textures. That’s why NASA and the authors are calling this the clearest potential sign yet—not a definitive detection. In other words, it’s a rock star, but not yet a mic-drop.

The river-and-lake strategy seems to be paying off

Perseverance has long targeted former rivers and lakes because water-rich environments concentrate sediments and organics—prime real estate for biosignatures to form and be preserved. Bright Angel sits along a quarter-mile-wide ancient river valley feeding Jezero’s paleolake, exactly the kind of setting where Earth analogs tell us microbial metabolisms leave durable mineral calling cards. The rover’s latest “leopard spots” are consistent with that blueprint.

So…is this life on Mars?

Not yet. NASA officials and mission scientists stress the careful language: “potential biosignature.” The textures and minerals could have biological origins, but alternative, purely chemical pathways have not been eliminated. Think of it as a high-value lead in a long investigation—compelling enough to energize the field, not strong enough to close the case. Independent newsrooms and NASA’s own briefings echoed that caution while still calling it the strongest hint so far.

What happens next (and why sample return matters)

To answer the life question with confidence, scientists need to interrogate actual pieces of this rock on Earth using instruments far more sensitive than anything we can fly. That’s the promise of Mars Sample Return (MSR)—a multi-agency effort to pick up Perseverance’s cached cores. Funding and architecture for MSR are in flux, but the scientific rationale just got a major shot in the arm: this is precisely the kind of sample you bring home to test biogenic vs. abiotic origins decisively.

The data behind the headlines

- Minerals detected: likely vivianite (ferrous iron phosphate) and greigite (iron sulfide), frequently tied to microbe-driven redox chemistry on Earth.

- Organics detected in situ: SHERLOC’s Raman spectra show a carbon “G-band” in Bright Angel mudstones, spatially associated with the iron minerals.

- Context: Lake-derived sediments in Jezero Crater from ~3.2–3.8 Ga (billion years ago), targeted as high-habitability strata.

Why this matters for astrobiology (and for us)

Astrobiology is moving from “could Mars have been habitable?” to “did it host life?” The Jezero result is impactful because it bundles the big three—water, organics, and redox-active minerals—into one outcrop with textures that hint at metabolism. If subsequent experiments (and, ideally, MSR) confirm a biological origin, we wouldn’t just be adding a Martian footnote to biology—we’d be rewriting the preface. Multiple origins of life in one solar system would suggest that biology is a feature, not a bug, of rocky worlds. That doesn’t just change planetary science; it reframes our own story.

Read the room: trending questions for 2025

- “AI-assisted spectroscopy?” Researchers are already exploring advanced analytics to compare Martian spectra with vast Earth libraries. Even now, the constraint is less software than ground truth—actual samples on Earth.

- “Could contamination be fooling us?” The organics appear embedded within the rock matrix and aligned with mineral reaction fronts, which argues against rover contamination. Still, Earth labs can test isotopes, trace metals, and microtextures at orders-of-magnitude better precision.

- “What if it’s abiotic?” Then we’ve learned how Mars’ geochemistry can masquerade as life. That’s valuable too—it tightens our biosignature criteria for Mars, Europa, and Enceladus.

The takeaway

Perseverance didn’t snap a selfie with a Martian microbe. But it did collect and characterize one of the most promising, testable rock samples in the history of the life-on-Mars hunt—exactly the kind of find we designed the mission to make. For now, curiosity is satisfied; certainty awaits a ticket home.