17000ft Connects Adventurists With Villages En Route

I recently wrote an article about an unreleased documentary, Motorcycle Changpa, which explores life in Ladakh, one of the most remote regions of the country. The folks at Dirt Track Productions expressed that the documentary was meant not only to expose a lifestyle that so many of us often forget still exists, but also to encourage viewers to visit this part of the country and to spend time with its people. Those who read the article or watched the film’s trailer might have been left with a feeling of intrigue, yet those, including myself, who felt moved to actually consider such an adventure were perhaps unsure of how exactly to approach the trip, or how to access these villages.

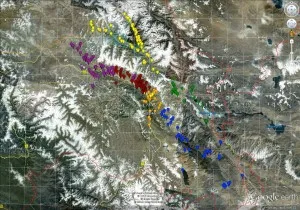

By working with open sourced software from Karnataka Learning Partners that they are customizing for their own purposes, 17000ft has been able to digitally map the 366 schools around the region in a project they call MapMySchool@17000ft. Each school will have its own page where visitors can share their experiences, update future trekkers on the needs of a particular school, share photos, and collaborate on projects.

“What we’re trying to do is to bring all of these villages onto a map of Ladakh and say look, this village has a school with 20 kids and 3 teachers, and it really needs teacher training, or this school is begging for someone to teach physical education,” explained Sujata. “What if you knew while you were going on your trip that something like this was right around the corner and a little bit of structured support from your end could go a long way in helping these people?”

“We realize we can’t rely on trekkers and travelers to bring about the change we need,” explained Sujata. “We’re going to do it through the help of local Ladakhis. Like I said joblessness is very high, on an average there are about 3-4000 graduates looking for jobs. We will hire them and give them the training they need. These people are motivated and enthusiastic, but there is no avenue. You can find Ladakhis who are graduates or post-graduates, but all he will be doing is probably being a tour guide.”

Indeed, tourism remains the primary source of income flowing into Ladakh, and is hardly adequate to sustain the 300-plus villages in the region. Despite the majority of the region covered by rural communities, harsh climates make it extremely difficult to grow crops for one half the year, and impossible for the other half. The challenges of living in this environment are expedited with their key economic pillar, tourism, being practically shut down for six months a year due to inaccessibility and snow covered roads.

“Before the winter starts they make their way out to the city of Leh, which might take them two to three days walking,” said Sujata. “Sometimes you can bum a ride with a car or truck that is driving by. And if you’re lucky you might have a horse or a donkey. So what they do is they go and buy as much as they can carry and bring it back to their villages to live off for 6 months.”

As one can imagine, this level of isolation in the region has an immense impact on the potential for development. High altitudes and harsh weather do not exactly appeal to everyone, and do not necessarily hold promise for business. The effects trickle down to the lowest levels of society. As Sujata explains, “The majority of the problems – the lack of education, healthcare – are because they are inaccessible.”

The first challenge that faced 17000ft, therefore, was, according to Sujata, “How do we get people to go up there, to spend two to three days travelling just to visit a school?” The solution was the trekking community. This is the beauty of 17000ft: the potential it holds to capture a niche of adventurists who actively seek isolation and high altitudes, who push their bodies physically and endure harsh climates purely for the thrill, serenity, and fun of it all.

“Lots of trekkers come into Ladakh, and lots of them are inspired enough to stay for a few months just to help out,” Sujata explained. “The idea is to tie all of these schools to popular routes. Not a lot of villages are on popular trekking roads. By sending people to these other villages, this increases the economic opportunities of these other villages.

The result is symbiosis. Apart from the invaluable sense fulfillment from helping those in need, trekkers benefit by being encouraged to venture into new land and explore new terrain. More importantly, villagers benefit through improved education, employment, and direct injections into their local economies. If made sustainable, these socioeconomic boosts have the potential to create a lasting improvement in lifestyle in one of the harshest regions of the world.

In the next four to five years, Sujata hopes to scale 17000ft’s services to 75-80% of the 900-plus schools in Ladakh. They hope to implement self-sustaining programs using locally staffed teacher development programs, reading workshops, school infrastructure development, and continued trekker and volunteer involvement.

Inspired to travel to Ladakh with 17000ft?