Around the time India Today magazine was born, every elected member of India’s Parliament used to have two special entitlements: a cooking gas connection and an additional telephone line at home. In a country of scarcity and regulation, hundreds of people queued up at their MP’s door to get these facilities from the “MP Quota” by trading some favour or the other, or simply by exercising the right of proximity. It was roughly at the time that I came to Delhi in search of work. It didn’t take long to realise that it was impossible for me to break the glass ceiling of ever owning a cooking gas connection or get a “residential telephone”, which would signal my personal success. Fortunately, upon marriage in 1980, my wife Susmita was gifted a gas connection by her mother. The so-called residential telephone, however, didn’t happen for almost another decade and a half. It was only in 1993, by when I had moved to Bangalore, that my employer, Wipro, got one installed in my house because I was running an independent line of business.

A few years later, people started speaking about a new thing: the cell phone. In 1996, I remember, when a young employee brought a cell phone, purchased with his own money, to office, he was seen as irreverent, brash and spendthrift; it was a matter of consternation at the corporate office as to how this might impact the frugal culture of the organisation.

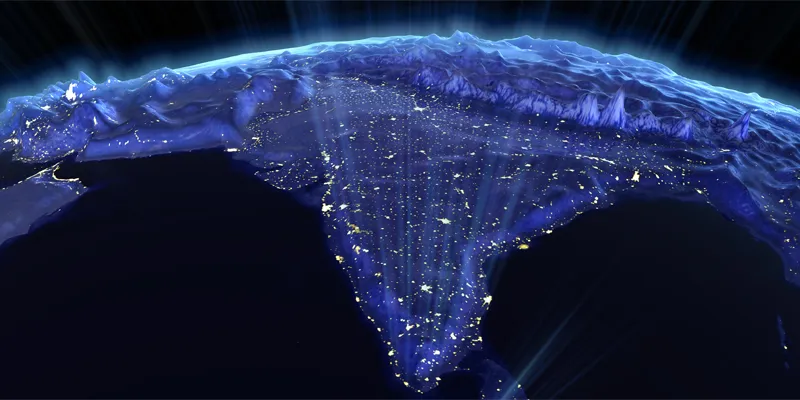

Image Credits : Shutterstock

Fast forward two decades. We live in a country where cell-phone penetration is the second highest in the world. According to the American intelligence agency CIA (who else!), for every 100 Indians, there were 74.16 cell phones in use in 2013. However, on a comparative scale, our internet penetration remains low at 15.1 per cent, though it is growing at a healthy 26.1 per cent (compound annual growth rate) over the last five years. When we look at India, the cellular nation with a rising internet penetration, we are confronted with this question: what does technology do to people? The answer is quite simple: it transforms them, it empowers them in ways never known before and it brings dignity to them.

To understand the full import of the argument, just visualise a streetside vegetable seller in, say, Malegaon without a cell phone. Now think of the same individual with a cell phone.

Imagine a fisherman on a dhow off the Mangalore coast, staring at an impending cloudburst, without a cell phone. Again, think of the same person with a cell phone. Finally, imagine a young Dalit woman somewhere on a dirt track in Kashipur, walking all by herself, without a cell phone. Pause. Now imagine her with a mobile phone in her hand.

The vegetable seller with a cell phone is likely to be a micro-finance borrower while the one without it is likely to be beholden to a usurer. The fisherman with a cell phone is more likely to send his girl child to school than the one without it. And the Dalit woman with a cell phone is more likely to insist on a planned family than the one without; she is more likely to take her baby for polio vaccination and she is the one more likely to cast a vote than the one who does not have a cell phone. Such transformative capacity of technology is generational but the question is: how far have we delivered on this possibility? How much more is left to be done for the 1.2 billion people who live in the penumbra of our consciousness? Over to flight 6E 491 from Bangalore to Bhubaneswar.

As the plane pushed back from the gate on time, I found myself thinking of our mission to Mars, Mangalyaan, that cost less than $450 million. After take-off, I found myself thinking about the entrepreneurial surge of the nation, of internet start-up Flipkart’s mind boggling valuation at $7 billion. At cruise altitude, my mind glided to the amazing newspaper report that soon, Amazon was going to deploy drones in Bengaluru, experimenting the delivery of packages in densely populated areas. Soon, I gathered myself. I thought of the purpose of my flight.

Today my flight was taking me back to where I once came from: the state of Odisha, where I was born the same year as the launch of the first man-made satellite, Sputnik. There, I was born in a place called Patnagarh, in a government quarter with no running water and electricity. The trip was significant for me in many ways. A child of the information technology revolution of the last four decades who has seen the world, I was on a quest to see the work of a little known eye doctor who had done 50,000 cataract operations for the poorest of the poor in the districts of Bolangir and Sambalpur and Kalahandi, the last of which invokes memories of starvation deaths and destitute mothers selling their babies. Today, I was returning to my roots after nearly four decades.

These have been defining years for me, as also for India’s journey from poverty to the G20 club. I had reasons to feel good. After all, India’s IT prowess had a big role to play in that journey.

After the flight, a six-hour train journey the next morning and then a car ride on a dusty road, I arrived at my destination: a hamlet called Jamadarpalli where 100 poor people had been operated upon for cataract.

These men and women were all crouched together in makeshift spaces, squatting on well-worn durries, their eyes bandaged. They were from a world that is beyond visualisation even when we mouth terms like “below the poverty line”. These elderly people were wearing the same kind of clothes, had the same frail figures that were frozen in my mind from my years growing up in these parts.

But they all sat there in hope; they would see again, they would step out of the shadow. They had been herded from their villages and brought to the camp, fed, operated upon, and after the bandages would be removed in a day, they would all be bussed back to where they came from. The men and women cheered our arrival, the women rented the air with their traditional “Ulululu” sound. Some of them prostrated without knowing who had come; anyone from afar was an angel to them and the doctor, an unassuming, idealistic young man named Shivaprasad Sahoo, was God.

I sat down and conversed with the villagers. Thank God, I hadn’t forgotten the language in all these years. They clasped my hand in theirs and narrated their stories. Then from the crowd, an old lady emerged and started crying. She was petitioning me that she had been set aside, that the doctors did not perform surgery on her and it was unfair because all the others had been operated upon. I looked at Dr Sahoo. He told me she had a high sugar level and unless they brought it down, they could not perform the surgery. Despite everyone telling her that she would soon be operated upon and that she need not be anxious, she remained pensive. She had no idea she had a high sugar level. She had no idea what it meant. I hugged her and told her that her turn would come, that she would be operated upon for sure, that she would be able to see like the rest of the villagers, that she would not be left behind.

The old lady held on to me, only half convinced. Dr Sahoo said this happened quite often. He narrated an instance where two old women had come for cataract removal and both were given vials to collect their urine. The two went off for the samples and soon returned. The tests indicated they had high sugar levels. As a result, they were taken off the day’s surgery list. At that point, one of the women protested vociferously.

Her sugar level was not high, she insisted. How could Dr Sahoo know she had a high sugar level? It was her urine sample that had just been tested, the doctor explained to her. Afraid and anxious, she blurted out the truth: it wasn’t her sample. How could that be, she was asked? It was then that she told the dumbfounded medical team that she didn’t have anything in her bladder so she had borrowed some from her friend, thinking it was some kind of a ritual before the operation.

There are three Indias that concurrently engage my mind. There is Jamadarpalli. Then there is the India that I live in, the India where information technology obliterates the distinction between the virtual and the real. And then there is the India where, one day, the old woman would not just be able to see but live with dignity, be a part of a resurgence; an India where she would not be a castaway, where we don’t just give her the ability to see but make her a central part of our vision. At the intersection of these three Indias, I see the pivotal role technology will play. Technology is not just about the utility it delivers, it has multiplicative powers and it is inherently transformative in nature. There is an alchemy to it. And yet, at its core, there is a void because it does not quite know the difference between greed and welfare. There is this India of wealth and power and unbridled private ambition. Across the digital divide from it, there is an India that is at risk because we lack empathy and a sense of inclusion. But there is a bridge across the divide. And I can see it.