Supplying dignity through e-commerce to Bengal's exploited artisans: the Rangamaati story

Abyss

Sanjay Guha Thakurta can recall the exact moment he decided he was going to be an entrepreneur.

The IT professional had been in the software industry for 15 years and was experiencing a career peak in his role as a department head of ARC Software Solutions. Then one evening, while at work, he experienced severe heart palpitations, shortness of breath and collapsed. He was rushed to the hospital where, after treatment and tests, the doctors concluded that he was suffering from a condition where the brain keeps getting deprived from proper oxygen flow. He was further shocked to learn that the genesis of this disease was psychological, not biological.

Sanjay says, “It’s not that I was afraid to die. I was afraid of dying without accomplishing something truly meaningful.” The next few months, living with the knowledge that he could die at a moment’s notice, he began to search for a purpose worth living. After four months of fruitless searching, he attended the Makar Sankranti festival in Kenduli in Bengal’s Birbhum district, for spiritual replenishing. Thousands of bauls (wandering singers in Bengal whose music are replete with rich folklore), fakirs, and hermits use this occasion to pay homage to the great poet Joydeb. Sanjay spent hours immersed in the songs of the bauls without understanding a word of what they were singing. “Their music brought me peace I hadn’t ever felt before in my life,” he sighs.

Light

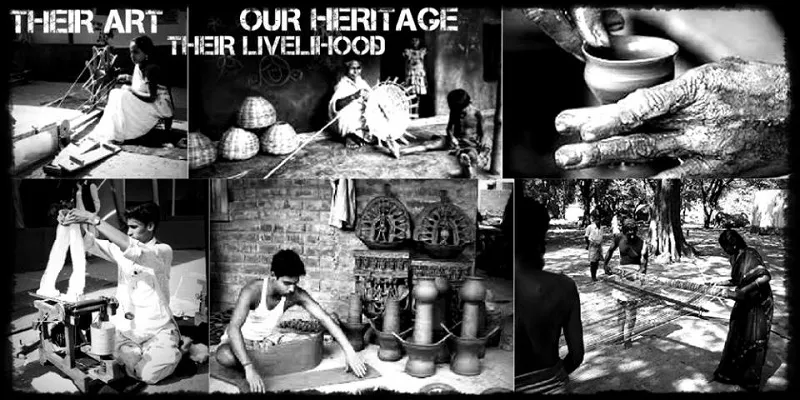

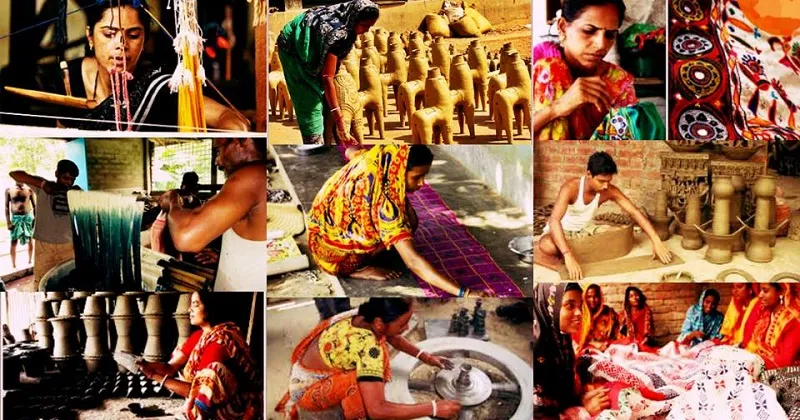

Sanjay says the songs of the baul guided him towards his destination. He continued with his day job, but on the weekends he travelled. “I travelled the length and breadth of Bengal in search of more bauls, fakirs, and their music. They fed me, sometimes even going hungry themselves to ensure their guest didn’t suffer. During these sojourns, I discovered village after village of potters, weavers, wood carvers, tribal groups working with Dokra and so on. I witnessed skilled craftsmen starving because the market didn’t appreciate their extraordinary skill. I saw artisans being exploited and heckled to death by middlemen.”

Although his soul had found the cause it was seeking, Sanjay, like most of us, was apprehensive about giving up a well-paying job and leap into the financial insecurities of starting up. He had a wife and a small son to take care of. But one day something happened that made him resign on the spot. “On August 16, 2013, I was asked to fire a couple of my juniors, without any justification whatsoever. The bosses wanted to create a sense of fear of recession since that was exactly the mood at the Fremont California headquarters so that no one asks for a salary review. I found myself at a point where I didn’t feel I would be learning something through dumbly executing management orders and left.”

The decision

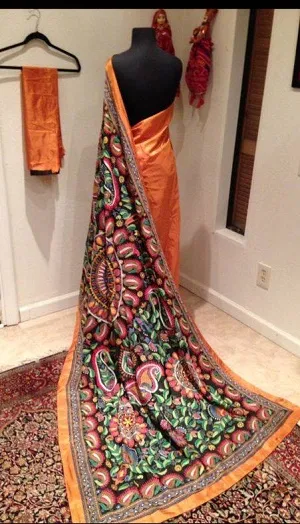

Sanjay decided that he was going to bring dignity and prosperity into the lives of Bengal craftsmen while introducing to the world the beauty of authentic Bengali heritage arts, crafts, and handloom through e-commerce. Thus Rangamaati was born in 2012. On the choice of name, Sanjay says, “Our work zones are primarily prevailing from Bankura, Birbhum, Bardhaman, Shantiniketan, and Purulia. The soil here is saffron red. Since the kaarigars, artisans and, the artwork prevail from the place of red soil, I named it Rangamaati. It reminds me of our roots, people, the compassion of the villagers and the wandering minstrels – the bauls, who showed me the path to this life. A life of self-respect filled with happiness, of learning, contributing and moving ahead as a whole.”

Troubles

Sanjay says that there has never been a more challenging time than now to market authentic artisan handicrafts. “Traders with huge pockets are entering the e-commerce market. They are selling machine made, easily replicable, items as the real thing and unsuspecting customers are buying it in the droves. This deprives the original craftsmen of their livelihood who are surviving in the throes of poverty. Many of them earn less than 500 rupees a month,” he fumes. He emphasises that these skills and techniques are passed down from generation to generation. Our modern day commercial practices are wiping out the last generation of skilled craftsmen while effectively eradicating the very existence of that craft.

He cites an example. Authentic dokra jewellery is made of chemical free organic alloy and will never irritate the skin. Cheap synthetic imitations online, on the other hand, will. When a buyer suffers these irritations, she will cast aside the jewellery thinking the dokra is to be blamed. “The sellers will move on to their next con game while the dokra makers are going to be cast out of the only job they’ve ever known,” he laments.

Sanjay implores to consumers to be conscientious shoppers, emphasising that the handicraft industry is one of India’s greatest assets. “India is one of the important suppliers of handicrafts to the world market. The Indian handicrafts industry is highly labour intensive, cottage based and decentralised. The industry provides employment to over six million artisans. In addition to the high potential for employment, the sector is economically important from the point of low capital investment, high ratio of value addition and high potential for export and foreign exchange earnings for the country. The export earnings from Indian handicrafts industry for the period 2012–2013 amounted to US$ 2.2 billion.”

E-commerce: the way forward

In the past decade, e-commerce has changed the way Indian industries function. Sanjay is hoping that this decade it will revolutionise how artisans create and earn. Instead of being beholden to middlemen or boutiques charging criminally high rates, they will be in touch with consumers directly. The consumer too will benefit from this exchange through this interaction. They will become more educated about the real thing versus the imitation. “We want to foster art lovers worldwide,” Sanjay exudes.

Financially he has had a numbingly hard time. After his own savings were exhausted, Sanjay took to surviving off his mother’s pension and selling off his wife’s jewellery. Some friends came forward to help, but it was not enough. He has grand plans of scaling Rangamaati, of involving the communities he works with, in the startup process. But he can’t raise the capital to do so. “Banks and governmental institutions turn me away because they find my idea laughable. Today, in India it is indeed laughable to want to give impoverished people a chance to stand on their own feet,” he says wryly.

Good news amid the bad

Despite the heavy lifting ahead of them, Sanjay says the milestones Rangamaati has achieved gives him hope for the future. “The biggest challenge for me was to get the artisans to trust me. Greedy middlemen have been swindling them for years. How would they know I was any different?” Now that they are on board with his vision, he thinks he can conquer the next set of problems with more ease.

Rangamaati also has a small, but steadily growing, dedicated customer base around the world. He regularly ships to USA, Russia, France and a handful of other countries as well as to regions across the nation. The Russian ambassador to India, Alexander M. Kadakin recently purchased an exclusively commissioned Dokra Goddess Laxmi. The haute cuisine restaurant Shorshe in Bangalore features a mammoth Dokra installation of the Goddess Durga and her offspring at its entrance. Sanjay says he dotes on each one of his customers; from the businessman commissioning huge statues to the impoverished writer lady in Delhi who pinched pennies to be able to afford a kantha stitch saree every month. “They are not customers,” he says with pride. “They are patrons.”