How Chandaben Shroff’s mission, started in 1969, is today empowering 4,000 women artisans in Kutch

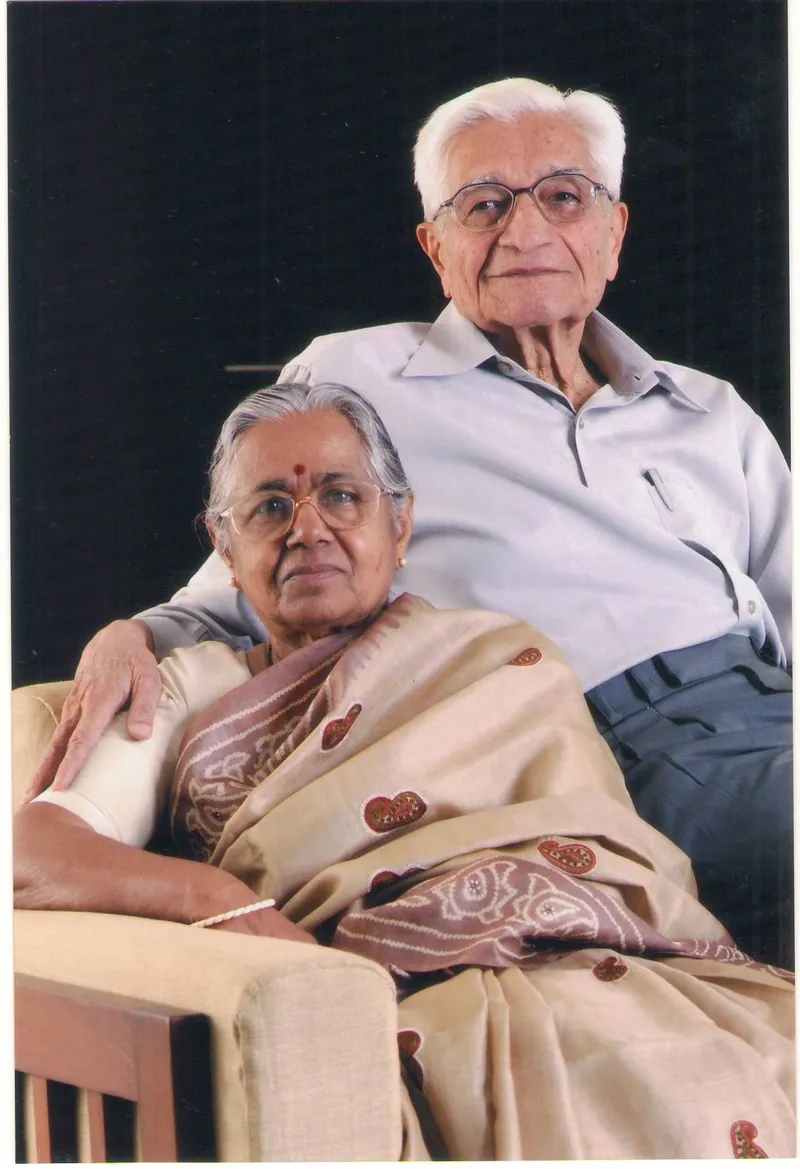

In 1969, Chandaben Shroff journeyed to Kutch, Gujarat, with the Ramkrishna Mission to aid drought relief efforts. Visiting Dhaneti village, she realised that the Ahir community there was reluctant to accept help packages, insisting on being given work instead, and several communities mirrored this sentiment across Bhuj’s villages. Another thing that all these communities had in common, from the Jaths to the Rabaris, to the Meghwaads and more, was the intricate and diverse embroidery done by their women. As Chandaben noticed this unique craft, she decided to experiment, testing the waters for what fruit they could bear. Buying 30 saris, she asked 30 different women to use the cloths as their canvas and adorn them with their embroidery. All those pieces were sold at an exhibition in Mumbai, with demands for more. And the Shrujan Trust was born.

‘Shrujan Trust’, a Bhuj-based NGO has been leading the charge for empowering women in the Kutch region. For the last half-a-century, the trust has dedicated itself to reviving the skill of making authentic and unique hand embroidered Kutch craft. This age-old art form has been practised by the artisans of Kutch for generations, but Shrujan has turned this heritage into a viable source of income, especially for the women in the region. From just 30 women in 1969, today it is a 4,000-member community spanning over 100 villages.

While Chandaben is still very much a part of the organisation, she has passed on the baton to her daughter, Ami Shroff. Ami was born five years after Shrujan was incorporated and she has literally grown up seeing the Trust go from strength to strength. Ami says, “While on one hand, I had to work hard to understand Shrujan and what it stands for, on the other, it has always been a part of our dinner table conversations. When I joined Shrujan full time, my mother was by my side, and that is the case even today. She is our guide and mentor in every step we take. It is her work, her ethos, and her vision that is ingrained in each and every person at Shrujan. She worked as a family member with each artisan that she interacted with, from day one, and that is the example we follow today.”

Living and Learning Design

It’s interesting to note that some of the women artisans have no formal education and yet are masters of a special form of embroidery called ‘Soof’ that involves mathematical calculations. Ami adds, “The complete embroidery is done on calculations which they keep doing in their minds while working on multiple pieces. It is amazing to see the kind of skill they possess and Shrujan is helping them preserve and enhance this skill and taking their work to urban and global audiences.”Shrujan founded ‘The Living and Learning Design Centre (LLDC)’ in January 2016. LLDC not only houses India’s biggest Craft’s Museum, but is also an active hub for crafts from the Kutch region. LLDC begins where Shrujan trails off. While Shrujan aims at providing a platform for artisans to earn a livelihood, LLDC has a larger agenda, that of ‘Preserving and Reviving the Craft Culture and Tradition’ of the Kutch region. It is a first-of-its-kind, kaarigar-dedicated, multi-dimensional craft education and resource centre. Ami says, “By the late 70s and 80s, embroidery would have vanished if Shrujan hadn’t come into the picture.”

Serving different audiences through LLDC

LLDC serves three groups – practising kaarigars, aspiring kaarigars, and rural youth irrespective of their skill and education level. It provides intensive, need-based training to practising artisans to strengthen their craft and make their products relevant and marketable. Seasoned artisans, who are the living legends of their craft, play a key role as teachers, mentors, and collaborators. Formal education and technical skills are not a prerequisite for learning at LLDC, making it accessible to anyone interested in crafts. Aspiring artisans and rural youth can therefore enroll at LLDC to learn a craft and practice it as a viable and attractive career option.

Ami adds, “This is one of the main reasons we envisioned LLDC in the rural areas of Kutch and not in a township. The LLDC campus lies amidst nine acres of fruit orchards near Ajrakpur village, 16 km from Bhuj, Kutch. Apart from the kaarigars and villagers, LLDC is dedicated to other audiences as well. It encourages urban designers to explore the potential of the crafts, provide a one-stop destination for craft lovers and educate urban visitors about their role in preserving and promoting the crafts.”

The Crafts Museum will serve craft lovers from all over the world with a one-stop destination to deepen their involvement with the crafts of Kutch, as well as promote greater collaboration opportunities between designers all over the world and karigaars present locally.

The second part of LLDC is its research wing. This part of LLDC will be dedicated to documenting the embroidery tradition of the Kutch region. Although Shrujan has been undertaking research work since as early as 2004, this wing will now enable them to research centuries-old embroideries and preserve them for future generations who can benefit from learning the tradition.

The third wing of is the ‘kaarigar-dedicated crafts studio’, which enables artisans from other craft areas besides embroidery to hone and explore new skills under the LLDC wing. Ami adds, “Currently we have potters, weavers, and even hand block printers working at the studios, who are learning new techniques and exploring new design ideas and adding their own spin of creativity to make new products that can marketed to a larger audience.”

With LLDC opening its doors, Ami hope to amplify the impact Shrujan has had. Ami adds, “We had over 1,500 women kaarigars travel over the three days for the opening ceremony, to witness the outcome of their work at LLDC. Some of these women were leaving their homes and villages and travelling for first time in their lives, just to see some of their communities’ traditional work being displayed proudly at the Museum or to see the center where their children now had a chance to learn a traditional skill.”

Dreams and Challenges

Ami says that while the LLDC continues to grow, the ultimate goal is to open a Crafts School that will run full-time courses and will have fully equipped working studios for all the 22 crafts of Kutch. Ami adds, “This will make LLDC the single-largest living and working craft environment in Kutch and perhaps in India as well.”

Ami says that while Shrujan has become a well-oiled machine since its inception 47 years ago, LLDC is their new baby that needs to be nurtured and grown with ample attention, help, and care. Ami points out a common challenge among entrepreneurs, “Funding towards running LLDC for it flourish to its fullest potential without compromising on our vision for the center is our immediate challenge.”

On a parting note, we ask Chandaben if she felt like a lone warrior fighting for the upliftment of a group of people when she founded Shrujan back in ’69. Her response is a strong lesson for all of us, The thought of being alone never crossed my mind, because I was too busy focusing on getting the work done, and my focus was on helping each artisan.” On the success and scale Shrujan has achieved, she says, “I was busy getting things done and never really thought about the scale. The growth happened organically as time went by, so we continued to put our head down and strived to empower the artisans we worked with.

On being a woman, she says,

I think being a woman gave me a better advantage, as I was more empathetic of their day – to – day struggles. I understood clearly the amount of things the woman of the house has to juggle, and the fact that she would need to work while handling the needs of her family as well. This made it easier for us to assign work to the artisans based on their free time, and also handle the delicate dynamics involved in a largely patriarchal set up.