Here's what unit economics of Zomato for food delivery looks like

In earlier posts, we spoke about what our online food ordering business has taught us, and how we built the transactions DNA at Zomato over the past year despite having been a content-centric business so far. In this post, we will zoom in and look at the unit economics of our online ordering business in India, and how things look for us in the future.

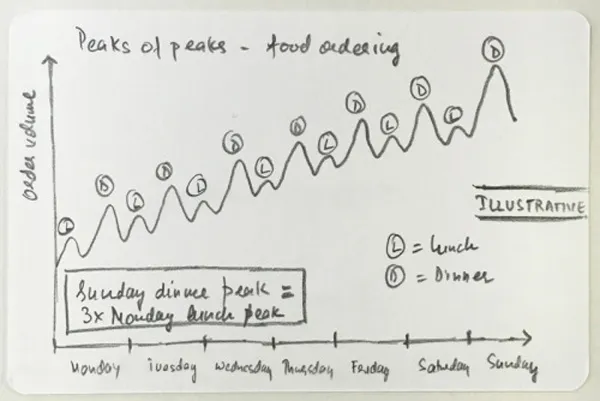

Before we go on, let’s show you how order volumes stack up during various times of the day, and days of the week.

We look at our unit economics on a monthly basis. Now, if you slice out the peak volume on Sunday, those four hours obviously have extraordinarily great unit economics. But the trick of the trade is to make your unit economics work over an entire month/week, which factors in multiple peaks and troughs.

In the month of May, we processed a total of ~750,000 orders, continuing to grow at an average of 30% month-on-month. We’ve grown our online ordering business in a sustainable manner, focusing on high average order values, consciously avoiding the discounting route, and putting a great customer experience at the core of everything.

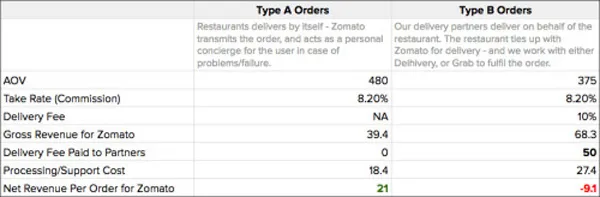

Of the ~750k orders last month, 80% of the orders were fulfilled by restaurants themselves (where we don’t do the delivery for them) – we call these Type A orders. 20% of the orders were fulfilled by us, through our last-mile logistics partners – we call these Type B orders. Keep this nomenclature in mind as you read on; this blog post analyses both Type A and Type B orders separately.

Here’s how everything stacks up for us.

The tldr; version of unit economics is in this chart below (all numbers in INR):

Note: In an analyst call a few days ago, we had said that the loss per order for Type B orders was Rs 2. That was because until last week, we used to average out our total processing/support cost over all received orders. However, now we have now started calculating processing/support cost separately for Type A vs Type B orders, and the loss per order for Type B orders comes out to be Rs 9.1

If you want to know more about the thinking behind each of these numbers, and how these are calculated, please read on.

Average Order Value (AOV)

AOV (sometimes also referred to as average ticket size or basket size) is the average value of an order during a period of time. AOV can be pre-discount, or post-discount, depending on how you look at it. Having said that, you can only gauge the real value of the business you are building if you consider the AOV post-discounting. Customers acquired through discounts are almost always going to be discount seekers, and not building that into your long-term unit economics means you are not being honest to yourself.

Our AOVs (post all possible ways to consider discounting) are Rs 480 for Type A orders, and Rs 375 for Type B orders.

Zomato doesn’t do much discounting by itself. Less than 2% of our orders are discounted by us, while 27% of our orders are discounted by the restaurants themselves. When restaurants discount something, we don’t call it discounting, we call it ‘pricing’. Just like airlines, or hotel prices, because restaurants push discounts on Zomato themselves to drive demand, using the Zomato for Business app (which they use frequently for review notifications, etc.).

Even this real-time pricing is built into the average order values for Zomato. Effectively, this formula is what holds true (and should hold true) if you are honest to yourself about your average order values –

(average order value) * (number of orders) = (total amount of real money transacted on the platform)

Take-rate/Commission/Gross Margin

This is the percentage of the total bill amount that the restaurant pays us for bringing them the delivery orders through our online ordering service. We have a variable commission rate for most of the restaurants on our network; the commission rate depends on the delivery experience for each order as rated by the customer – the better the experience, the lower the commission. While it might seem counterintuitive to do this as against charging a flat commission rate, it incentivises restaurants to provide better experiences, which leads to better customer retention.

For us, this is averaging out to 8.2% in the most recent month for Type A orders, and 18.2% for Type B orders (which includes an extra 10% for delivery).

Related read: What the financials of online food ordering biggies Swiggy, Foodpanda and Zomato reveal

Here’s the math for this.

Type A orders, commission – AOV * Take Rate = Rs 480 * 8.2% = ~Rs 40

Type B orders, commission – AOV * Take Rate = Rs 375 * (8.2% + 10%) = ~Rs 68

This means that we have Rs 40 to play with for Type A orders, and Rs 68 to play with for Type B orders. That’s our gross margin on each order, on an average.

For type A orders, we need to make sure that the total order processing cost – including payment gateway fee, order processing fee, support cost – is less than Rs 40 per order.

For type B orders, there’s an extra cost we incur per order which is the delivery cost, and we need to make sure that the sum of order processing cost and delivery cost is less than Rs 68.

Now, let’s talk about Delivery cost.

Delivery cost

Applicable to us only for Type B orders, this is the cost incurred to deliver a single order. This is a loaded cost, which means it includes salaries for delivery staff, the equipment and vehicles they use, as well as training and administrative costs. We pay Rs 50 to our delivery partners per order on an average (more on that later).

But it costs our delivery partners Rs 62 to fulfil an order they receive from us. An important point to note here – despite our business being extremely spiky, our delivery partners (Delhivery and Grab) are able to work in a relatively cost-efficient way because they can do e-commerce and grocery deliveries during our lean times (when food ordering is not at its peak). So Rs 62 is extremely good already. There’s room to make it better, and we are together working on predictive tech to make route planning better for delivery personnel so that this cost can come down to around Rs 50 per order.

Another important point to note – Rs 50 will eventually only possible if you are able to keep delivery personnel busy during lean periods for food orders (which they do by serving e-commerce and grocery). Oh, and by the way, this math doesn’t factor in the very high recruitment cost of delivery personnel because of sky-high attrition.

We are thankful to our delivery partners to work with us to grow this part of the business. If we were to do this ourselves (and we’ve had the urge to do it multiple times), we would end up ruining the unit economics for the entire company in one shot. Because of the spiky nature of the business, the delivery cost would work out to ~Rs 105 per delivery. Of course, in some dense areas, during peak times, this can be much lower. But over a month, over all the markets you serve, it makes no sense at all, and you will lose more money than you can ever imagine recovering in any way possible.

And we haven’t yet gotten to the order processing and support costs yet, which is next.

By the same author: What 2015 taught us at Zomato

Processing and Support Cost

Processing cost includes the telco data fee we incur when we automatically transmit a new order over to the restaurant. However, sometimes the device at the restaurant’s end has a bad signal, and we have to then make an SOS call to them to get the order processed. Our network is designed to have 95% automation, but it ends at 80% automation because of data/battery issues at the restaurant’s premises. Obviously, automation is way cheaper, easier, and quicker than making a call to relay an order.

Then there’s the support cost, which is what we incur when something goes wrong, and the customer raises an issue with our support team.

For Type A orders, we only have a two-way conversation to handle – between the customer and the restaurant. For Type B orders, we have a three-way conversation to work with – the customer, the restaurant, and the delivery partner’s person who is on the road.

Our total processing and support cost for Type A orders adds up to Rs 18.4 per order. For Type B orders, it adds up to Rs 27.4 (primarily because of the three-way calling, which adds more support agent time, and tariff to the cost stack). Three-ways aren’t always a good thing.

Six months ago, our support cost was about Rs 50 per order – we’ve managed to bring this down to current levels with automation, and by making hundreds of micro improvements. There is no silver bullet to bring this cost down – you have to keep chipping away at this cost bit by bit. And that’s what makes this business exciting and endless. Save a rupee per order, and the unit economics start looking way better than they did before.

Another thing this cost includes is the payment gateway fee, which is not borne by the restaurant separately (35% of all our orders are now paid for online). The number of restaurants accepting online payments on Zomato has gone up drastically in the past six months. In addition to a smoother product experience for customers, it also significantly drives down the cost associated with cash collections, and prevents pilferage – something that is very hard to control with a large delivery fleet, even if you own it.

A founder of a now-defunct local grocery startup once told me that their entire net revenue got wiped out due to cash pilferage at the hands of delivery personnel. Interestingly, he wasn’t taking that into account when calculating unit economics, and was adding these costs in the corporate overhead line item of “Miscellaneous”.

Net Contribution Margin

Net contribution margin = (AOV * Take Rate - Delivery Cost - Processing Cost)

This is what contributes towards the overall profitability of the business, and has to, over time, offset the fixed cost of the business.

Customer acquisition cost (CAC)

This is the marketing cost. This is beyond unit economics and fixed costs. How much CAC you incur, depends on how much money you are willing to spend to acquire each customer into your transaction funnel, and at what pace.

India’s CAC to LTV (life time value for a customer) ratios are very bad. Some companies are even acquiring a transacting user for as high as Rs 1200. Why’s that so high? We pay extremely high prices to various marketing channels in addition to discounting for customer acquisition.

Also, most e-commerce/transaction businesses have a traffic problem. They need to spend large amounts of capital to re-engage customers i.e. getting them to transact again on the platform. On that note, the Priceline group spent $2.8bn last year on online marketing, and Amazon spent $3.8bn. Unless customers visit the platform for something else (e.g. content, reviews, photos, and sharing) and then naturally move into the transaction flow, it is very hard to drive high re-engagement rates for commerce platforms. And that’s exactly what makes it easy for us at Zomato – our classifieds business, where we have 8.5 million monthly uniques in India alone. And so far, less than 3% of them are ordering from us. There’s massive room to grow before we think of paying big $$$s for marketing.

Fixed Cost

Sales teams, engineering teams, analytics and business teams. This cost stays fairly the same over time if you are adequately staffed here. Over time, the total net contribution margin should become more than the fixed cost, which will give you…

Profit.

This might have needed explaining in 2015. Not anymore.

(Editor's note - this post first appeared on Zomato's blog)

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory.)