Bonanza – banks can tap annual digital transaction fee pool of Rs 1.5 lakh cr!

ICICI Bank, HDFC Bank and Axis Bank’s move to charge cash transactions is not to be seen as one driven by greed, but as an offshoot of the big shift that’s happening in banking, and should be welcomed.

That it was going to happen was a given, just when was the question. That question has now been answered.

You can curse private lenders ICICI Bank, HDFC Bank and Axis Bank for their decision to restore or hike the charges payable on cash transactions waived off during the demonetisation drive. But what’s gone largely unnoticed in the attendant din is the marked shift that’s on in banks’ income streams. If their state-run brethren have not bitten the bullet on this front so far by charging for services to reflect their real costs, it’s a cause for alarm, not cheer.

Before we come to matters of detail, here what’s in store in the days ahead.

Bank unions are not amused, and are set to take up the matter with the Reserve Bank of India and the Indian Banks' Association (IBA) – a lobby group of bankers – for what they term a patently “anti-customer move”. Just how seriously the powers that be will take their views remains to be seen; they have not gotten a considerate ear on any issue of late.

It’s also bonanza time for banks if one were to take a cold, hard look at cash, its costs, and the reality of the banking business as it stands today.

Digital banking carries a cost that’s to be borne by someone. Currently, the fee is around 2 percent; it can hopefully come down to 1 percent once all constituents -- banks, card companies and payment gateways -- agree to lower their charges given the high volumes. Just how they will go about it, however, is not clear.

Madan Sabnavis, Chief Economist at CARE Ratings, explains,

Assuming Rs 150 lakh crore, which is our GDP, goes digital, even at one percent, the total cost would be Rs 1.5 lakh crore for the system. It’s good for the suppliers of services, but would at the same time impose a high cost on the system -- households and traders who have to split the cost.

Now, this fee-pool is for all players to tap into, but the lion’s share is for banks to carve out for themselves.

So, will we get fleeced? Well, yes and no. And just how did we land in such a situation?

The Backstory

Over the past few years, the pressure on banks’ capital has gone up. Every time a bank vends a loan, it becomes that much harder to squeeze out a decent return on it. And if it were to turn out a dud, banks have to set aside capital for provisioning. Just look at the trendline on the non-performing asset (NPA) front.

Mint Road’s latest Financial Stability Report (December 2016) notes that the gross non-performing advances ratio of banks – that’s before provisioning for bad credit – went up to 9.1 percent from 7.8 percent between March and September 2016. It pushed up the overall stressed advances ratio -- inclusive of dud loans restructured to give borrowers a fresh lease of life -- to 12.3 percent from 11.5 percent.

What this means is that banks will remain risk-averse for some time to come as they clean up their balance sheets; their capital position may remain insufficient to support higher credit growth.

And in the current context, it’s a no-brainer to be tight-fisted on loans given the hassles involved. But then again, you also have to deal with someone somewhere to be in business.

Enter fee-based income.

… and it’s not a case of going for the jam

This is not to remotely suggest that greed to boost fee-income is behind the move to “reset” pricing on cash transactions. In the current context, it’s being completely misread, especially on social media. You have to question those who say they withdraw more than four times by going to a branch. It can mean only one thing – the counterparties with whom they transact want to do so in cash. And why should that be the case when the digital mode is well within reach? At least for those who know how to go about it.

Compared to loans, which fetch a bank interest income, fee income is a better bet. You employ relatively less capital, and every time a customer transacts – swipes, remits or hawks its own or a third-party’s insurance or mutual funds (MF) – you get to pocket a fee.

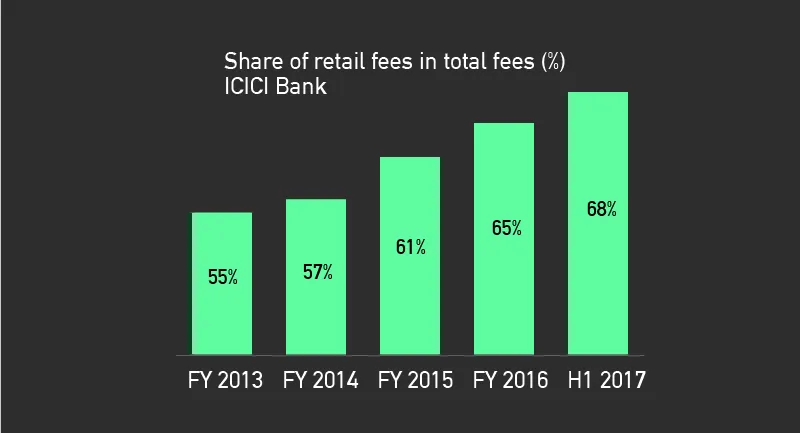

Here’s what ICICI Bank had to say in its Annual Report for 2015-16. Fee income primarily includes fees from corporate clients (loan-processing and transaction banking) and that from retail customers -- loan processing plus fee from credit cards business, account servicing charges, and third-party referral and distribution fees. In fiscal ‘16, its fee income rose 6.4 percent to Rs 8,820 crore on the back of buoyant transaction banking fees and third-party referral fees, which the bank says “was offset, in part, by a decrease in lending-linked fees”.

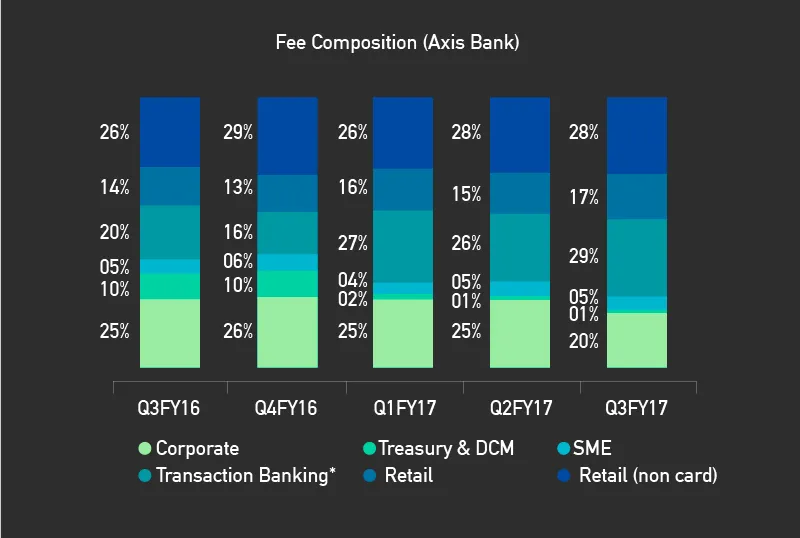

In its investor presentation to i-bankers CLSA in November 2016 in New Delhi, ICICI Bank said that growth in fee income has been subdued since fiscal 2014 given the focus on re-orienting corporate lending and weak corporate activity. But on the retail side, fees have been higher due to the focus on cross-selling of third-party products to existing customers, its leadership in distribution of insurance, and large MF distribution.

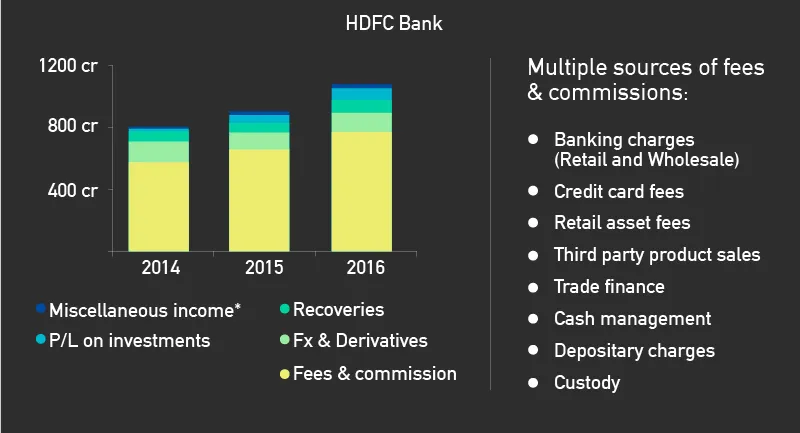

Likewise, arch rival HDFC Bank, in its Annual Report for 2015-16, highlighted the same aspects.

Total net revenues (net interest income plus other income) was up 22.1 percent at Rs 38,343.2 crore. “Other income” grew 19.5 percent to Rs 10,751.7 crore; the largest component was fees and commissions, which were up 17.8 percent to Rs 7,759 crore -- the primary drivers being commissions on plastic, transactional charges, fees on deposit accounts, fees on retail assets and commission on distribution of MFs and insurance products.

Open the annual report of any sensible bank in the country and you will read the same narrative. Simply put, lending is the lowest form of banking, right at the bottom of the food-chain.

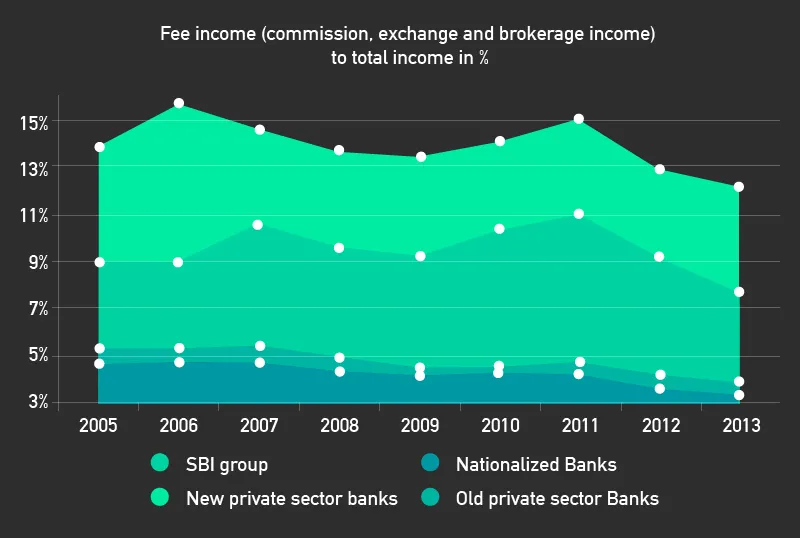

The report by the P. J. Nayak (the former boss of Axis Bank) Committee to Review Governance of Boards of Banks noted that, in recent years, fees as a proportion of operating income were significantly higher in new private sector banks. At the end of March 2013, fees were 7 percent of operating income for the SBI group, as low as 3 percent for other state-run banks, and 12 percent for new private sector banks.

A weak counter-narrative

Where does all of this leave digital banking and financial inclusion? Are you and I to pay the price for banks’ greed?

Vishwas Utagi, general secretary of the All India Bank Employees Association, says, “Digital banking is supposed to reduce costs; here, we are talking the opposite. To the extent, you are to be charged so heavily for this, the effective return for you as a depositor is also lower.”

On the face of it, this approach by banks (select as on date) runs contrary to what the Nachiket Mor Committee on Comprehensive Financial Services for Small Businesses and Low Income Households (2014) had observed.

In its roadmap, by 1 January 2016, each low-income household and small business was to have convenient access to providers that have the ability to offer them suitable investment and deposit products, and pay reasonable charges for their services. The point is that this may not happen anytime soon.

Given the stress on the dud-loan front, pressure on capital, and low margins, it makes perfect sense to chase fee-income, and price services accordingly. That this should be the focus was highlighted by M. S. Verma’s (a former chairman of State Bank of India) `Report on Restructuring Weak Public Sector Banks’ way back in 1999. The report read,

“Despite their weak bank image, these banks are able to garner deposits obviously because of government ownership, deposit insurance, and the public perception that government support would always be available… they are slipping in other key areas of their operations… and income from non-fund based business is not growing or is growing very marginally. The capability of these banks to do the full range of banking business in a manner that would result in a healthy bottom line is, therefore, being further impaired.”

The report added that these banks operated almost entirely on a single revenue stream, namely, interest income. That such dependence on interest income has impacted their earning capacity very adversely in a falling interest-rate scenario is clear.

Think about it again; we are in 2017; many state-run banks are very much in a similar position to 1999; and we are also in a falling interest-rate scenario.

It’s argued that compared to private banks, the state-run ones have refrained from charging you heavily. The truth is that several of them are weak; they are losing market share rapidly. By 2019, their share may well fall to about 50 percent of banking assets from the 70-odd percent now, says Crisil. And contrary to what you may think, state-run banks’ service charges are not “reasonable”. You and I, as taxpayers, are the ones doling out for their recapitalisation, although this “hefty charge” is not apparent.

It’s also misplaced to contend that unlike non-banks, depositors are the “real suppliers” of capital – the argument here is that the capital adequacy ratio is at 9 percent; and banking is a highly leveraged business. Or in effect, depositors should not be penalised for using their own money.

This would have been valid had operational cost issues not been what they are; or if there had not been the heavy preemptions by way of reserve norms -- a 4 percent cash reserve ratio and 20.50 percent by way of the statutory liquidity ratio. In effect, Rs 24.50 of every Rs 100 in bank deposits is off the table upfront for commercial India. Then, you have the 40-odd percent that’s to be given to the priority sector; all kinds of rules to make you a partner in nation building. Add on the deadweight of NPAs, Basel-III capital norms, which kick in from 2019, and operational expenses. And at the end of all this, you are also expected to keep something on the plate for your shareholders.

Whichever way you look at it, it’s high time banks priced their services to reflect real costs. ICICI Bank, HDFC Bank and Axis Bank have shown us the way forward.

Three cheers to them!