How this couple uses tech to help tribals claim ownership of their land in rural Gujarat

Ambrish Mehta and Trupti Parekh provide GPS instruments to village-level Forest Rights Committees to conduct surveys of land that tribals claim rights to

This is a story of perseverance. One among many long-drawn-out tales in this large democracy called India. We’re talking of a region in the Narmada district of south Gujarat where the river is close to flowing into the ocean. The tribals have lived here for a long time, but we’ll talk of a timeframe from the early '80s, when the government of India reached out to these far-flung areas to bring them under governance. It was also a time of revolution, and in Gujarat, the Narmada Dam project was being heatedly criticised.

Ambrish Mehta and Trupti Parekh are a couple that found themselves in the middle of this struggle. Trupti had an MA in English Literature and Linguistics along with a Bachelor of Law while Ambrish graduated in Biology but deeply moved by the state of the situation, they got into action to stand for the tribals and became part of a group called ARCH- Vahini (Action Research in Community Health and Development) that cared about the implementation of the government’s rehabilitation programme. The group started work back in 1980 for proper rehabilitation of the families, who lost their lands and houses for the Sardar Sarovar (Narmada) Dam Project and played a crucial role in getting, what is widely recognised as unprecedented, rehabilitation policy for these families in 1988. And thereafter they worked for the next 10 years to ensure that this policy is actually implemented on ground.

Moving to the current time, the Forest Rights Act (FRA) provides for giving titles to all tribal families who are occupying forest land from or before December 2005 for self-cultivation and/or habitation. Close to two lakh tribals have filed claims to get such titles, but are not in a position to give credible evidence in support of their claim that they are occupying/cultivating the land from December 2005.

Ambrish and Trupti have developed a simple method of using GPS instruments and satellite Images to generate maps with satellite images (of 2005) in the background to overcome this difficulty. “We provide GPS instruments to the village-level Forest Rights Committees, and they carry out the GPS surveys of all plots of land that tribals in their village have staked claimed to.

“We use simple Garmin Etrex 10 or 20 instruments for this purpose. The method used is that of area calculation, so that the farmers can see the actual map and area of their plot on the instrument itself,” Ambrish explains. The tracks are saved along with the date and time stamp, and the details of the farmer's name, and file and plot number. The data, together with the sheets of paper, are then brought for further processing to Ambrish.

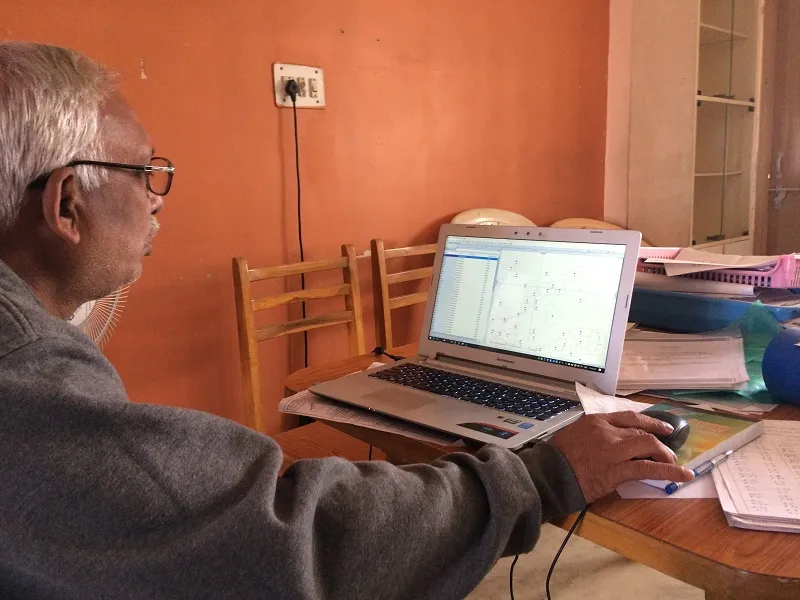

The couple then processes the GPS data on a GIS programme. “Each plot has to be individually processed to correct overlapping boundaries or remove gaps between adjoining plots and also to give plot numbers to each plot,” he adds.

After more processing, a spreadsheet and two GPX files (GPS and Sat) are uploaded on their website —www.righttoproperty.org — and plot reports are generated and downloaded.

The maps with Satellite Images (of 2005 and latest) are generated offline from the GIS programme. This way, RightToProperty has played a pivotal role in helping tribals get their rights. “It is a long-drawn-out process, but tiny successes here and there keep us going,” says Trupti, who has travelled far and wide in the rural parts of Gujarat, where this issue is widespread.

The couple has managed to leverage tech and fight for justice by remaining in the confines of governance. But the problem is becoming larger than they can handle. Ambrish has processed more than 4,000 cases, but there are more than 20,000 lined up. “The map of each plot showing both boundaries and satellite image in the background is to be generated individually, and as such is quite time-consuming. We have carried out GPS surveys for more than 20,000 claims so far, from which the task of generating plot maps showing both (GPS and satellite) boundaries with satellite images of 2005 and 2014 has been completed for about 4,000 claims,” Ambrish notes.

The data for these claims is being reviewed by the government authorities and the couple expects their decisions soon. Once this process starts gaining momentum, there would be a huge increase in demand for such maps from other claimants, and the duo would need to generate such maps quickly on a larger scale. This is where they need help currently.

This is a wonderful case of technology being used for better problem resolution, and it is acting out as a true leveller. As technology penetrates the hinterlands of India in a more meaningful manner, we’ll realise the positive sides of technology, and how it can be used for thoughtful development.

If you’re in the field of mapping and programming and would like to get involved in this issue of land rights, write in to [email protected], or call Ambrish on 9825411540.