Business model scalability: applying the concept to adopt the right model

We as venture investors love highly scalable business models. 'But what does that mean in simple terms?' has often been the question thrown right back at me. On the other hand, I continue to interact with entrepreneurs who choose a highly scalable business model over a relatively lesser scalable business model even though the latter is clearly more effective in solving a real customer pain point (read ‘Disaster’).

The following post is an attempt to conceptually understand ‘scalability’, identify key drivers of business model scalability, provide a framework to understand the scalability of a particular business model, highlight why the venture community loves scalable models, why I personally hate business models that choose scalability over effectively solving for consumer pain point and, finally, highlight some of the drawbacks of highly scalable business models.

Business model scalability

Conceptually, scalability is the relative ease with which a business grows. All businesses grow and hence, are scalable, having said that some business models are relatively easier to grow rather than others. I bet you have heard that an “online marketplace e-commerce model is more scalable than an inventory-led e-commerce model” or “its very hard to scale a consulting business”. I will try and explain that below but what I need your takeaway up till now to be the term ‘relative ease of growth’.

Which then leads to the question that what decides the ‘ease’ of growth? Essentially, two things –

(1) How much capital does the business model need to generate incremental growth? A t the cost of stating the obvious, ‘growth’ requires ‘investment’ – be it in the form of marketing or building infrastructure (putting up retail stores and warehouses, building a power plant, developing a website). For example, once a power plant hits stable capacity, the company needs to outlay a huge sum of capital to build another power plant to drive top line growth. Offline retail businesses need to add stores at a rapid pace to continue to drive growth. Compare this to an online marketplace like eBay – the company needs to continue to spend on marketing, improve product or add geographies with little incremental spend to grow top line (read ‘much easier than the power plant or offline retail businesses’)

(2) What kind of human resource does the business require to generate incremental growth? I would categorise human resource in two broad buckets:

- Low cost, high productivity labour force completing commodity tasks – commodity tasks are simple tasks that a person can perform repeatedly with basic educational qualification. Given that the person repeats the task day in and day out, he/she becomes more efficient at it over a period of time. Key examples include delivery executives, pickers and packers in warehouses. As long as such a labour force is in abundance, they will be easy to find and replace and, as a consequence, have low payouts.

- High cost, low productivity labour force completing complex tasks – complex tasks requires a person to have good educational qualification and experience. Every complex task is unique and, hence, productivity can be low given that there are little or no efficiency gains from the last task. Key examples include venture capitalists, consultants, R&D experts. Such a labour force is hard to replace easily or for that matter quickly and will have high payouts.

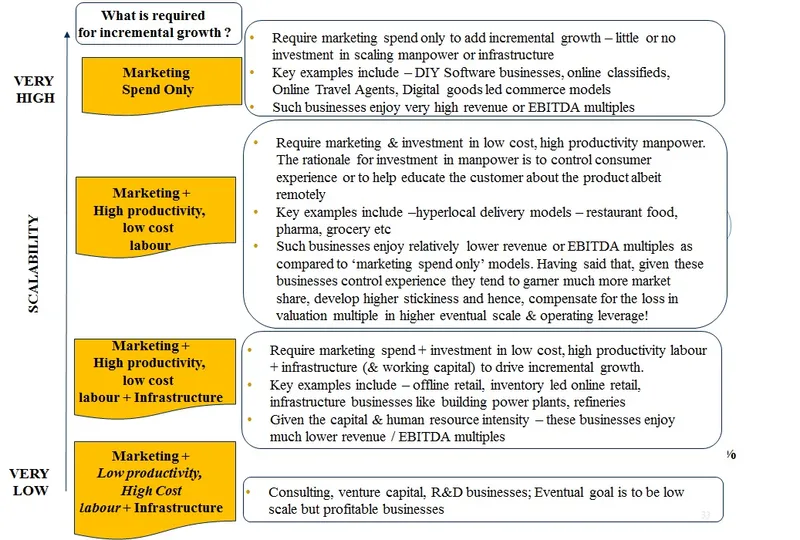

Keeping the above two parameters in mind, the following is my attempt to build a ‘Business Model Scalability Stack’ – this should enable businesses to better understand the relative scalability of different types of business models.

Business Model Scalability Stack

VCs love for highly scalable business models – scalable business models grow fast (this, of course, assumes that there exists a large market). This means that the business has the opportunity to become large in a short period of time (read ‘dream of every venture capitalist and entrepreneur’). Large scale and growth brings fat valuation multiples, which means high valuations and high returns.

While all this sounds really good and seductive – scalability and total valuation (read ‘not valuation multiple but the final valuation in $’) might not have a linear relationship always.

The fact that entrepreneurs are choosing scalable business models over business models that solve customer problem in the most efficient manner is a testament to the fact that there exists over-simplification in their understanding of scalability and valuation (more on this in the next section).

Why I hate models that choose ‘scalability’ over ‘solving customer problem effectively’ – Don’t get me wrong, I am not dissing highly scalable business models (I am a VC!) but pursuing a scalable business model (at the cost of consumer experience) in pursuit of high valuation multiple is a super risky game which can result in existential risks and also, highlights rather shallow understanding of valuation.

Why the existential risk – consumers gravitate to business models that are a combination of Better (read ‘better experience’), Cheaper, Faster and Reliable (I call it the BCFR framework. Although fairly self-explanatory, I will detail this out in another blog.) The more letters of the BCFR framework in your model the better it is. For example, cab aggregation model ticks all four aspects of the framework. Assuming unit economics of the business works, the founder needs to add all aspects before thinking about scalability. Leaving out one of the aspects could result in competition cropping up, consumers alienating the company for the more attractive value proposition, company then attributes loss of market share to marketing (rather than attributing it to a business model flaw and hiding under the garb of ‘scalability’) Higher marketing results in higher burn – fund raise timelines change – negative surprise for both internal and external investors – high burn and lower growth are ripe conditions for down round or a shut down.

Valuation (I cover more valuation drivers here: ‘Meet the Valuation’ – Understanding the Key Drivers of Early Stage Valuations)- is a function of two things of a performance metric (EBITDA, PAT, Revenue) and a valuation metric (function of growth, ease of growth or scalability, cash burn, risks). In my limited experience, models that adhere to the BCFR framework might not be as scalable and, hence, will lose out on a fat valuation multiple but will compensate for the lower mulitple through a much higher performance metric – higher market share and lower marketing spend of revenue (consumers love to drive organic or word-of-mouth-led growth) resulting in a much higher EBITDA.

Concentrate on improving business model scalability that maximises customer value – In this regard, I continue to challenge portfolio companies to build more technology and product to further improve business model scalability without sacrificing BCFR framework or a high quality consumer experience. For example, build product to improve delivery executive efficiency or warehouse picker efficiency.

Highly scalable business models attract competition very quickly – ‘ease of growth’ also means lower complexity which in turn means lower entry barriers. Highly scalable business models can quickly witness competition from similar business models, often resulting in a highly capital-intensive battle for both leadership and existence. Having said that, more credible risk to such models comes from competitive models that keep ‘consumer experience’ before ‘scalability’.

Changing business model mid-way is possible theoretically, but involves a lot of pain in reality – Pivoting a business model halfway into scaling operations can be very painful. Why? Most often, such pivots involve ‘de-growth’ or ‘dramatically slow growth’, coupled with cash burn or layoffs, which then comes in the way of high valuation investors have paid for the company or the CEOs tricky task of explaining the reduced value of ESOPs to key employees. Add to this changes in business goals that result in changes in organisation structure, lack of clarity early on that results in disillusioned employees, changes in processes and systems that also mean changes in product – both internal and customer facing. I am not saying it's not possible but is extremely hard to make the shift both quickly and successfully without taking all this pain.

In conclusion, business model scalability should be an outcome and not an input to the choice of business model – maximise on the BCFR value proposition framework and then optimise scalability.

Company needs to concentrate on improving business model scalability, through investments in technology and product, rather than chasing it at the cost of consumer value proposition. Valuation chasing, on the back of highly scalable model, can be great in the short run but can eventually result in existential risks.

Happy scaling up!

More at www.thenetwortheffect.com