Back to basics: when mud, bamboos, and timber houses help fight climate change

From climate-friendly homes of yore to monotonous concrete and glass structures of today, we are losing out on aesthetics and warmth. Thankfully, there are people who are reviving the time-tested practices.

The beauty of living in a place like India is that after every few hundred kilometres, it seems we are in a completely new place. The people change—their clothes, their language, their lifestyle, everything changes. And so is true of the architecture of these places.

An ideal way to notice this would be to travel to the countryside. Moving from the dense cites to the rural parts of India, the houses seem thinly scattered. Their design, material, planning, and orientation changes; and one can sense the increasing influence of urbanization. And this influence has damning effects.

In our quest of globalisation, by transforming our cities to make them the next Shanghai and Dubai, we are leaving behind a very strong part of our cultural identity. The shift in architecture—from the traditional, unique, and contextual to the modern, monotonous, and general—has become more rapid than ever.

If we sought inspiration from our roots, we would evolve our own unique forms of architecture instead of imitating others. In villages, people have successfully built their shelters and dwellings using local materials, through trial and error over time, with their own skill sets. They have done this in harmony with nature while understanding the climate. Now, a distinct change is evident—cement and concrete are replacing lime and stone, tin sheets are replacing clay tiles, buildings are replacing houses.

How people thrived

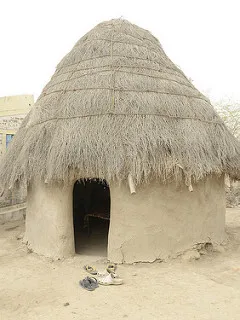

The obvious myth attached to local and traditional houses is that they are not strong, and are maintenance unfriendly. However, every possession of ours needs care and nurturing, and to understand this, we just need to look back at the 2001 Gujarat earthquake—where the only houses that did not fall were the circular bhungas of Kutch.What makes these houses so unique? The circular bhungas are mostly found spread across the banni grasslands of Kutch. This grassland sits on the most intensive earthquake zone 5. The houses are made round and small using a construction method called wattle and daub—wattle being the sticks/dried grasses that have been weaved together, and daub being the earth to bind it all together.

Some houses also have decorative bas-relief work done with earth plaster and tiny mirrors generally in the interiors. The entrance to the house is small, the floor is made from earth, and a layer of cow dung is poured on the floor. The walls too are layered with cow dung ‘lipai’ or ‘lipan’. The interiors are dark and the conical thatched roof prevents the entry of too much light. There are small circular openings towards the bottom of the walls that allow the air to be condensed before it enters, resulting in cool air flowing through the openings.

The combination of these materials, form, and design of the house results in greater climatic comfort than one would experience otherwise. The circular shape of the house makes it earthquake resistant, and even if it does fall, it is light, harmless, and can be easily and cheaply built again.

Another interesting study would be of the traditional houses in the hills of Himachal Pradesh, which also lie between earthquake zone 4 and 5. Despite the climate, culture, geography, and lifestyle being so different from Kutch, the people here too have evolved a system of earthquake resistance. Using the local materials of stone and timber, the houses are built on a high plinth with a construction method called ‘Kath-Kuni’. Alternate layers of stone and timber are laid without any mortar to make thick walls that can resist the forces of the earthquake.

The floors of these houses are made from timber, which does not get cold easily. Cattle reside in the bottom part of the house, and the houses are so designed that the heat generated from the cattle and from the kitchen can be used to warm the house. Features like these are unique to different regions of India.

From north to south, east to west

In Rajasthan, earth and stone buildings and systems of water conservation have existed for ages. In regions near the Aravalis, people build their houses using a technique called ‘rammed earth’. All measurements of the house are calculated by the distance between the tip of the owner’s hand till his elbow. This measurement unit is commonly called ‘haath’.

Further up in Udaipur, one can find ancient stone havelis that are over 250 years old. In Jaisalmer the local yellow sandstone is abundantly used. The use of ‘chuna’(lime) as mortar in stone buildings was prevalent and this lime has still retained its strength. The use of lime also allows buildings to breathe something that does not happen with the use of cement (the base of which is lime).

In Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and the rest of the North East, the use of bamboo has been pre-dominant in all aspects of life—not just for homes. Furniture, cutlery, arts, crafts, and also houses are fully dependent on bamboo which is an easy material to work with. A mature, cured bamboo of the right species can last a lifetime.

In Kerala, some of the traditional homes— called Nalukettus—are built around courtyards that have a significant impact on the house not just architecturally but also socially. The courtyard is the heart of the house around which all other rooms are built giving light and life to every room. It is also the place where the family gathers and women, especially, make the most use of these courtyards. As an exterior place within the house, women can be freer than they are outside. The courtyard also helps in the circulation of air by letting the hot air escape from the house and pulling in cooler breeze through the windows.

Courtyards are a common feature throughout the country and serve different purposes in different regions. Courtyards in Rajasthan, for example, are primarily used for ventilation and also for the collection and storage of rainwater. Along the coast of Kerala and further north towards Konkan, houses are built using red laterite stones called ‘chira’. These stones, being semi-porous in nature, allow walls to breathe, thus having a direct positive impact on the humidity and temperature of the building.

Why the change is for worse

There are a few reasons why the paradigm has shifted from traditional, colourful, and practical to monotonous structures. For one, the people themselves are overwhelmed by what they see in cities, movies, and in the media. They now aspire to build concrete buildings, as it is an upgrade to a pucca house—a symbol of power, status, and respect in today’s world.

Bamboo and mud are being looked down upon as a poor man’s material. This notion has drastic effects on people as they find it difficult to get their children married if they live in a mud house. The true understanding of the word ‘parampara’ or ‘tradition’ is an evolution—of culture, lifestyle, and ritual—and if this evolution of our architecture had taken place through the years (rather than a jump), nobody would have looked down upon mud and bamboo.

However, in spite of intentionally choosing to build with modern materials today, the interesting thing about Indians is that they will happily, passionately, and even nostalgically give a list of benefits of traditional houses over the current ones.

Another reason for the decline of traditional architecture has been the promotion of industrialised materials. An example for this would be the galvanized iron sheets or tin sheets that have effectively transformed the landscape of villages all over the country.

At places where once country tiles, Mangalore tiles or thatched roofs could be seen, flat slabs and tin sheets rule today. These tin sheets are cheap to buy and easy to fix but they have huge disadvantages. Besides the fact that it is a processed, industrialised, and unnatural material, tin sheet when not fixed properly can be easily uprooted by heavy winds causing severe damage. These tin sheets are extremely thin, and let through tremendous amount of heat during the day, making the temperature inside the house higher than outside. At night, the house is colder than the outside.

Cement, steel, etc. are easily available and marketed as materials that will last a lifetime with zero maintenance—but this is not true. The government has also adversely affected the situation. Instead of promoting vocational trainings, cultural arts and crafts, and traditional skills, it has envisioned a method of development that is based on the industries. This makes it difficult for anything but the industries to survive in the market, thus forcing several artisans to leave behind their age-old occupations and migrate to other areas in search for different, often menial jobs.

The government has also played a negative role after natural disasters when entire villages are wiped out. For instance, after the 2010 cloudburst in Ladakh, it provided prefabricated rooms made of galvanised iron to people. However, these rooms could not protect them against the severe Ladakhi winter as the traditional mud brick rooms which insulate houses from cold weather.

Some hope and efforts at revival

There is a slow movement in India and the rest of the world to bring traditional architecture to the forefront by using technology hand-in-hand with artisans who work with local and natural materials. In Himachal Pradesh, Didi Contractor is reviving the traditional earth and timber houses. In Gujarat, organisations like Hunnarshala Foundation, People in Centre, and Thumb Impressions have been instrumental in working with artisans and crafts-persons. Buildaur in Auroville, Malak Singh and Put Your Hands Together in Mumbai are also examples of people and organisations working towards a better, more sustainable architecture.

The government too has become more open to sustainable holistic development. Instead of building mass concrete house blocks after the 2008 Kosi floods in Bihar, it formed the owner driven rehabilitation collaborative (ODRC) with some of the above mentioned organisations. The main aim of ODRC was to promote bamboo (or brick) based houses depending on the needs of each of the affected families. The project was successfully tested with two pilot projects in 2010, and the government has continued this method of construction and rehabilitation till date.

Another example has been the development of houses under Indira Awas Yojana in Gujarat. The government has been studying various forms of traditional architecture all over the state and is exploring the idea of linking it with the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA). The aim is to get people to build their own homes according to their choices by following certain technical guidelines.

Together with the initiatives of the government and the people, the possibility of creating more sustainable and humane architecture is a dream that can be turned into a reality.

Disclaimer: This article, authored by Areen Attari, was first published in GOI Monitor.