Is India equipped to handle 1.3 billion aspirations?

With 33 births a minute, 2,000 an hour, 48,000 a day which calculates to nearly 12 million a year, India needs to disperse its urban economic hubs to accommodate the growing population.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has often addressed his fellow citizens as “sava sau crore deshwasi”, a phrase in Hindi which equates to almost 1.3 billion Indians. What he addresses with pride is also one-fifth of world's population and the second most populous country in the world. India is slated to become the most populated country in the world by 2022, surpassing its neighbour China while the size of the demography is said to cross 1.7 billion population by 2050.

Naresh Narasimhan, Bengaluru based Architect and Urbanist, believes that,

The economic reforms of 1990s enabled the country to take a leap from the neutral gear to the third gear directly, missing out on the first two gears. There is an intention to develop, but the power is still not there. Planning is not a very well-thought-out discipline. And considering the size of Indian cities, there is a need for city managers.

The economic reforms of the 1990s coincided with a tremendous rise in population—in the census from 1991 to 2011 the escalation was from 888.5 million to 1.2 billion. In his book, Social Development in India, Prof Ramesh Chandra states,“India currently approximately faces 33 births a minute, 2,000 an hour, 48,000 a day, which calculates to nearly 12 million a year.”

This multiplication in the demography has been due to several factors. The predominant case being the increasing birth rate. The issue of birth rate is buckled with poverty as having more children supposedly leads to more earning hands. Further, the rise in the birth rate can also be credited to several cultural factors such as inclination towards having large families, lack of sex education, social evils like child marriage, and poor access to contraception, especially in the rural areas.

On the contrary, the death rate has gone down due to improved medical facilities. These factors reflect well in the country’s average life expectancy which has increased from 32 in 1947 to 68 in 2014.

The great divide—urban and rural

With the economic reforms of the 1990s, the ball game changed with private players owning up the economy and India taking on the road to accelerated development. However, this development was lopsided.

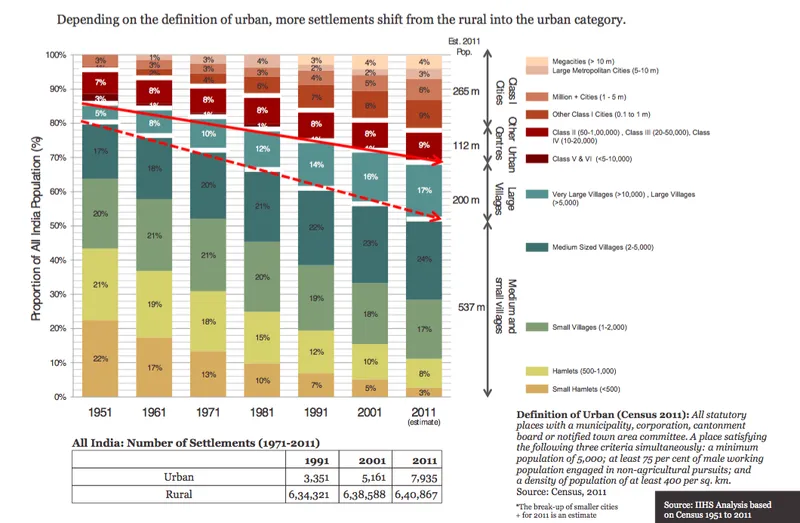

The notion of development since independence has been urban-centric. A sole focus towards industrialisation and urbanisation has led to a one-sided growth. Till date, 68 percent of the Indian population resides in rural areas.

“India is a land of villages”, says Naresh, the Principal Architect at the Venkataramanan Associates. He further states that urban centres in India were not big enough earlier to merit “that much attention.” Most of them were mid-size towns.

Bengaluru in the 80s and 90s had the right amount of water, right number of people, right amount of land—everything was right. It was a cooler place, he recalls.

Calling urbanisation a phenomena Naresh says,

At the turn of the century, 1900, 80 percent of Americans lived on farms; only the 20 percent lived in cities. By 2000, just two percent still lived on farms and 98 percent moved to towns and cities. That is how dramatic change happens. While that took 100 years, the Indian story has just started in the 1990s. And unlike the West which has been built and rebuilt over the century, in India we are trying to get it right in the first time itself which is very tough.

This urban-centric narrative of development has created a great divide between the rural and the urban dweller. Even though majority of the Indian population continues to live in the rural setup, there is substantial rural to urban migration leading to a rural-urban interdependence.

For instance, in the rural areas, farmers are dependent on the urban market; rural households are dependent on the urban centres for various services. Simultaneously, the urban centres depend on rural areas for raw materials and food supply. This dependence turns into disparity as villages, unlike cities, fail to have an easy access to education, health facilities, drinking water, power and pucca roads, among others.

Rural India is still synonymous with the agricultural sector which witnessed a sluggish growth rate of 1.2 percent in 2015-16. On the other hand, the industries and services sector grew at 7.4 percent and 8.9 percent respectively. Hence, the lack of job opportunities and growth becomes one of triggering factors for large-scale migration of labour forces from rural to urban towns and cities.

The magnetic pull of cities

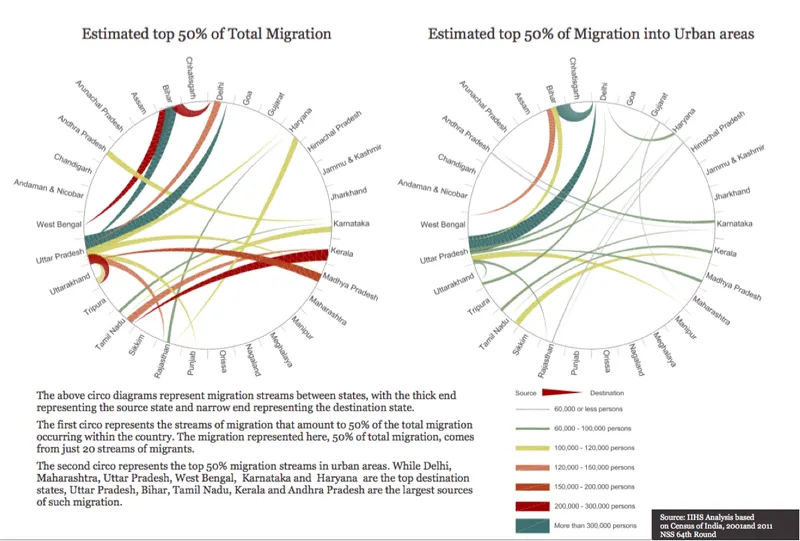

According to the Socio-Economic Caste Census (SECC), nearly 833 million people migrate to urban centres in search of employment. Further, the National Sample Survey Organisation, 2007-08 recorded the rate of rural to urban migration at a staggering 35 percent. The 2016-17 Economic Survey stated that at 2.1 percent compound annual growth rate (CAGR), India will take over China by 2031.

This pace of urbanisation is problematic considering that the entire country’s economic activities and growth are centred around cities, primarily the five metropolitan cities. Discussing the housing problems faced by the migrating population largely in Gurugram, Arti Jaiman, Station Director at Gurgaon Ki Awaaz Samudayik Radio, says,

The migrants working in the unorganised sector come from villages. The local landlords have built 20-30 rooms with shared bathrooms and they rent it to the labourers for a cost ranging between Rs 2,000 to Rs 3,500 per room.

This population shift puts immense pressure on the city’s resources, be it housing, infrastructure or water, electricity supply, thereby forcing ghettoised community centres concentrated in urban slums. While migration narratives are often viewed with a negative lens, Arti believes that the migrant communities build a city.

“Globally, all economies grow only because of migration. Thirty years ago, when there was no migration, Gurugram was a village. When industries and migrants come in, a city gets developed. It is never the locals alone who build a city. Try visualising any city without migrants, it will just die. We don't have to stop migration, rather, we have to plan housing, schooling and health care for the migrant population so that even they have equal rights within their own country,” Arti says.

India needs 'intelligent cities'

There is a need to disperse this growing floating population as cities cannot continue to grow endlessly, given the limited resources available. Hence with the aim “to promote cities that provide core infrastructure and give a decent quality of life to its citizens, a clean and sustainable environment and application of ‘Smart’ solutions,” the Ministry of Urban Development launched the Smart City Mission in 2015.

However, Naresh believes that India requires Intelligent rather than Smart Cities. Urban planning needs to be viewed from a sustainability paradigm. Advocating for the need to create multiple urban centres within a state and shift the political and policy focus to processes rather than projects, he says,

You have to fix other places—push policy towards infrastructure and economic growth. More importantly, you have to handle the growth and development with local talent, with local capacity, with local bureaucracy.

Ahmedabad, lauded for their slum rehabilitation programme, stands to become a model for tier-II cities in the country. Keeping pace with the dynamic demands of the city and its citizens, the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) along with the Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA), have incorporated various amendments to the existing rules “to deal with the problems of rapid urbanisation and growth of economy”.

Initiated in 1990 with the aim to raise the living conditions of the economically weaker sections, AMC has constructed more than 20,000 houses to rehabilitate families living in the Sabarmati Riverfront Project surrounding area. Further, the municipal body is constructing more than 30,000 units, of which more than 14,000 have already been completed and allotted.

For the in-situ slum rehabilitation, projects in 46 slums have been taken up where more than 24,000 units will be constructed. Ahmedabad Municipal Commissioner, Mukesh Kumar says,

What has worked with AMC’s slum rehabilitation programme is winning the trust of the slum dweller. The timely delivery of houses with quality construction to the beneficiaries has helped in convincing more citizens for such projects.

As a part of the Smart City plan, Ahmedabad aims to make public transport system accessible and reliable by combining the ‘Integrated Transit Management System’ and ‘Common Card Payment System’ with the existing rapid bus transit and Ahmedabad’s municipal transit system. Further, by converging various state and central government missions, the city corporation has vowed to redevelop an existing area of 75 acres from the ground up, thereby providing houses to more than 7700 families.

Whether Ahmedabad is successful in its attempt to become a lighthouse in the narrative of urban redevelopment is still to be discovered in the future. However, the city has at least initiated a conversation about exponential urbanisation. But can we say the same for other Smart Cities where urbanisation and population still remain in disarray?