Story of 65-year-old lawyer who is fighting for rights of workers and children in Delhi

While people from the economically weaker sections (EWS) are hesitant to approach judiciary, a Delhi-based lawyer is fighting for their rights and making their lives better.

In the chamber number 483 of the Delhi High Court, a man in his 60s is often seen surrounded by people seeking justice. These people are from the deprived section of the society. The man, Ashok Agrawal, is an advocate who has fought many battles for the poor in Delhi through the power of Public Interest Litigation (PIL). He helps them without charging a fee.

Ashok Agarwal is known for his untiring efforts to make good schooling and health facilities accessible to the poor. His PILs filed through ‘Social Jurist’ – an NGO run by him – have played a significant role in bringing changes in admission irregularities and lack of basic amenities in state-run schools.

Ashok started practising law in 1976 in the Delhi High Court. Coming from a trade union background, Ashok says he had closely observed the inhuman work conditions of poor workers and it motivated him to fight for their fundamental rights. He started fighting cases for labourers. Slowly, he took up the fight for free medical treatment and education for poor, in private hospitals and schools built on the land given by the government at subsidised rate.

In 1997, he filed his first PIL on education in the High Court, which raised the issue of arbitrary fee hike by unaided recognised private schools in the national capital. The same year, he filed another PIL raising the of lack of basic amenities in schools run by Delhi government and Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD).

Thereafter, many PILs were filed on issues related to education. With the aim to achieve the constitutional goal of an egalitarian society, Ashok says his fight is against inequality and unjust discrimination. If children from poor families are now being admitted to private schools for free, and patients from EWS are getting beds in the private hospitals, a share of the credit goes to Ashok Agarwal.

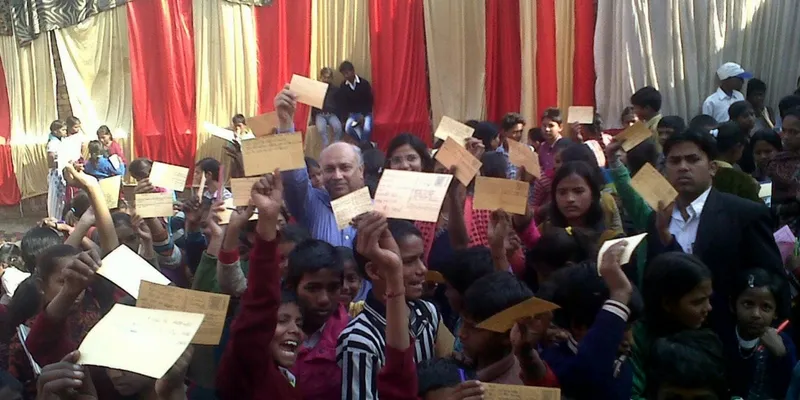

In 2010, Ashok initiated a unique way of seeking justice. He encouraged hundreds of children studying in government and MCD run schools to write postcards about the problems they faced in schools. Tired of their complaints falling on deaf ears, nearly 200 children wrote postcards to the Chief Justice of Delhi High Court highlighting the abysmal state of their schools. Their efforts paid off and their complaints were converted into a PIL which sought a response from the Delhi government and MCD.

Ashok, 65, says that while the response from Courts have always been encouraging, unending legal battles are tiring and demoralising at times. “The purpose of these PILs is to wake up the authorities and bring a change in the unjust and discriminatory system, but when the authorities are totally insensitive to the needs of children and particularly children of the poor, how long one can go on fighting? However, I am determined to continue to fight till my last breath,” he says.

Over the years of his fight with the unjust system, Ashok says that the government has not been interested in the education of children of the impoverished masses.

“I don’t see any change in the government’s response in all these years. The system is so designed that the poor has no place. There is a clear nexus between politicians, bureaucrats, and the corporate. People are the only hope,” he adds.

He recounts the two major victories of his struggle. These include the admission of children belonging to weaker sections to unaided private schools built on public land to the extent of 20 percent, and the free treatment of EWS patients in 47 identified private hospitals to the extent of 10 percent IPD and 25 percent OPD strength. He says that over the years, children have benefited a lot and the judgments pronounced by the Courts have played a significant role in framing the Right of Children for Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009. Ashok had also filed a PIL on the issue of fee hikes in schools and felt satisfied when in 1998 the court ordered 531 private schools to return excess fees to parents. Recently, a petition has been filed in the Delhi High Court for extending the benefit of enhanced minimum wages to around 65 lakh workers.

Nevertheless, the existing laws are in favour of the establishment and against the poor. While private schools are fleecing hapless parents, the government schools have been non-functional for long, says Ashok.

“In India, still more than 10 crore children of school-going age are out of the school system. Nearly 2 crore children with disabilities are out of the system. Child labour is rampant. All schools run by the government need to be upgraded to the level of Kendriya Vidyalaya and fee in private schools needs to be regulated by law to curb commercialisation and exploitation,” he adds.

Ashok says his social work has never affected his practice of law. Rather, it has always helped him meet more people.