Is a breakthrough moment round the corner for India’s foodtech startups?

YourStory speaks to Deepinder Goyal of Zomato, Rashmi Daga of Freshmenu and Shan Kadavil of FreshtoHome to know more about the challenges and the way ahead for the foodtech sector.

Food is integral to life in India; many of us discuss what we will eat at the next meal while enjoying our current one. No wonder then that the Indian food market was worth $193 billion last year and is estimated to cross $540 billion in three years.

Is it any surprise then that a number of entrepreneurs are drawn to this sector? It has all the right ingredients—large market, high repeat customer potential, opportunity to use tech for disruption and a chance to be creative.

But, rather than producing numerous success stories, foodtech is notorious for the many startups that shut down. Things went especially wrong for foodtech startups in the latter half of 2015 and in 2016 with companies like TinyOwl, Dazo, Zupermeal, Spoonjoy, Eatlo and EatOnGo among many others stumbling and either shutting down or opting for distress sales.

This year, too, has seen some high-profile shutdowns in the sector. Kalaari Capital backed on-demand meals delivery startup EatFresh shut shop in January, while cloud kitchen startup Yumist stopped operations in September.

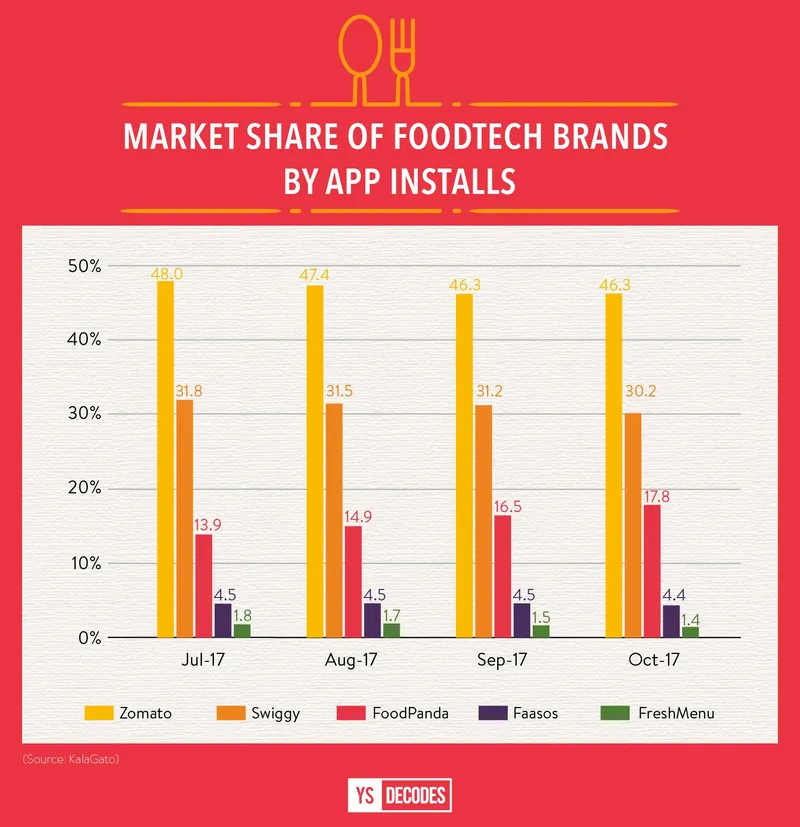

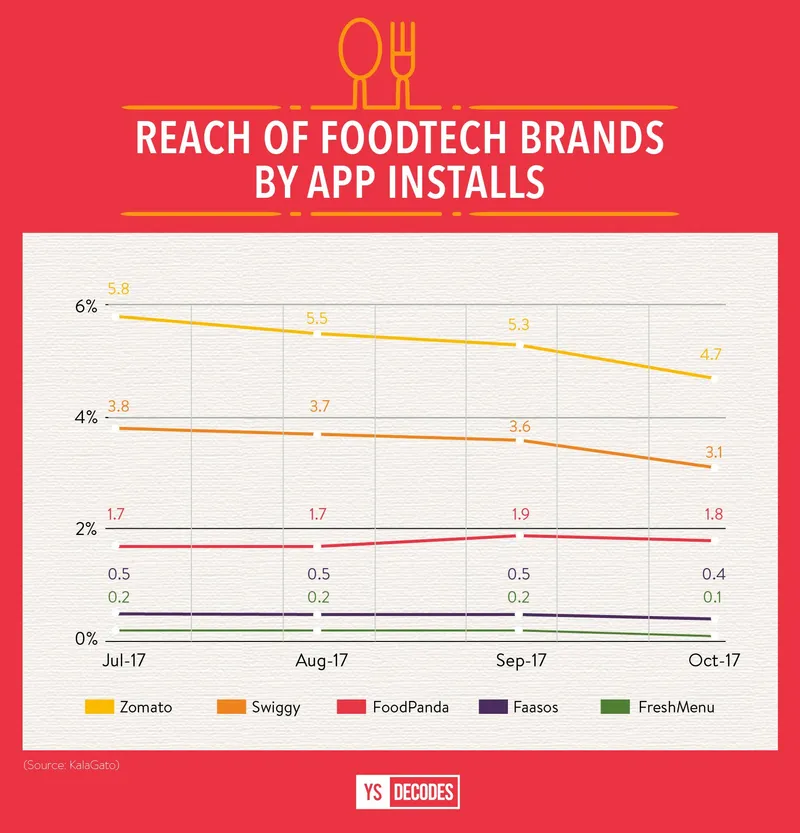

Zomato, Swiggy, Freshmenu, Foodpanda, Faasos and Innerchef are among the few startups that have managed to carve out a market for themselves. So, what’s really going on in this sector?

Let’s take a look at the post that Yumist founders Alok Jain and Abhimanyu Maheshwari put up on their site when they announced the halt in their operations. Among the many issues they raised, this one stood out: “We failed to raise the kind of capital that this business required while staying true to the customer problem.”

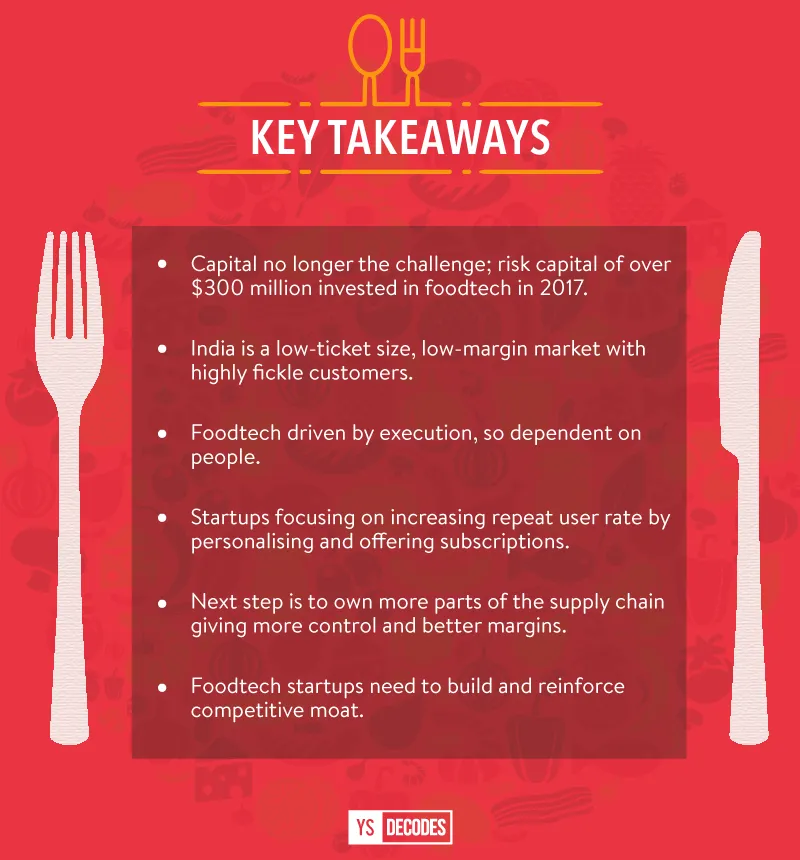

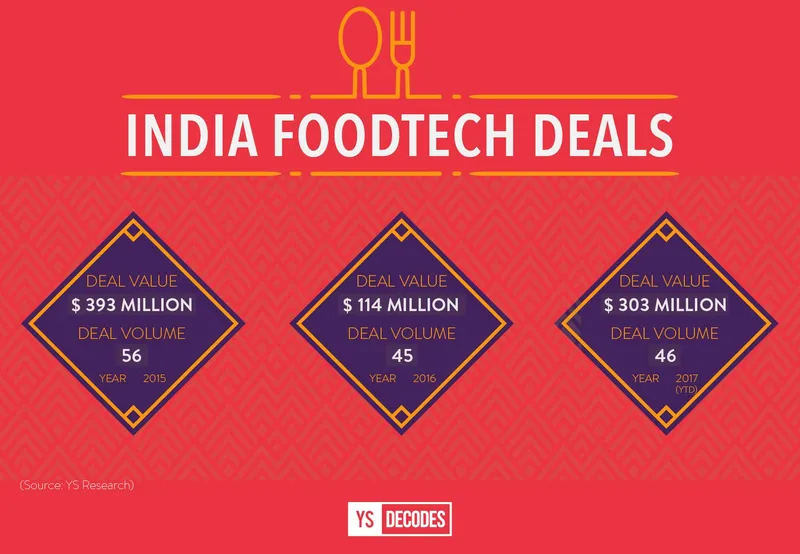

Is it really a matter of lack of capital? Sure investors have been cautious. The flood of capital in 2015, especially in hyperlocal and foodtech space was followed by a bloodbath with many startups in these two sectors shutting shop. Unsurprisingly, in 2016 foodtech attracted less than 30 percent of the funding that the industry got in 2015.

However, there has been a revival of sorts in investments in foodtech in 2017 with over $300 million funding until October.

Investors that YourStory spoke to over the last few months have consistently said that they will invest in startups with strong fundamentals and are addressing a large market.

Considering capital is not as big a problem now, YourStory spoke to three of the top players in Indian foodtech—Deepinder Goyal of Zomato, Rashmi Daga of Freshmenu and Shan Kadavil of FreshtoHome—to understand what the current challenges are and what it will take for a breakthrough.

The bitter butter

Deepinder, who founded Zomato in 2008 and is now one of the most experienced entrepreneurs in foodtech, says issues like changing rules, number of licenses required, high real estate costs, and problems with training and retaining staff are issues that have traditionally plagued the food industry. They’re something tech can’t really solve. He says:

The biggest problem facing the foodtech sector today is efficiency. India is a low-ticket size, low-margin canvas for the foodtech sector to operate in. If 90 percent of the restaurants out there are losing money, it becomes very hard for foodtech companies to charge an adequate amount of money from the user/restaurant in order to make the unit economics work. This means that only companies that are able to drive frugal innovation in India while creating value for consumers as well as restaurant owners will thrive/survive.”

Rashmi Daga, Founder of cloud kitchen startup Freshmenu, points to the challenge of changing customer tastes and lack of customer loyalty.

“Customer choices change every few months. The price points, what's in fashion and what's not, these change every few days. You as an entrepreneur need to think how to cater to that,” Rashmi says. “Food is an execution-driven business and is less driven by innovation. It is driven by how do you manage people, processes, execution and manage expectations.”

Foodtech is also an operationally intensive business. There are few sub-segments within foodtech that do not require heavy investments in people. For instance, Freshmenu operates 27 kitchens across Bengaluru, Mumbai and Delhi-NCR and employs around 2,000 people, including delivery staff. At the current growth rate, the employee number will jump to 6,000 in the next three years.

A large part of the problem is getting and retaining skilled and trained manpower. There might be talks of robots but that is still years away from becoming a reality. Our business will be people driven. Food cooked by chefs fresh is what will rule for us,” says Rashmi, who started Freshmenu in 2014.

The Freshmenu model focuses on offering a new menu to customers each day, chefs preparing the meals in cloud kitchens and the deliveries happening in about 45 minutes. With food being prepared in-house, Freshmenu needs a skilled kitchen team. It, along with most top players in the industry, has opted to have its own delivery team. This gives better control and ensures it can meet its promise of getting the food to the customer in a short time.

Other foodtech models are also people intensive.

Food delivery startup Swiggy, which recently forayed into the cloud kitchen business, has a delivery fleet size of 20,000.

The reason why these operational complexities become a big challenge is the low average order value.

Shan, Co-founder of fresh seafood and meat delivery startup FreshtoHome, says:

The biggest issue is strategy—it should make pure bottom line common sense. You have about Rs 20 to Rs 30 per order to play with. If delivery is Rs 40 and customer acquisition cost is Rs 100, then the model will collapse. That is what happened with a set of earlier startups. This model sinks the business if capital is the problem.”

So what have these companies done and are now doing to ensure they can grow sustainably?

Sugar and spice, and everything nice

Zomato continues to be the big daddy of foodtech in India. The company recently crossed the three million deliveries a month mark. This is in just two years since launching the meal delivery service. It has 25,000 restaurants on its platform in India, including 7,500 that are exclusively available only on Zomato. It had revenue of Rs 333 crore in FY2017. While losses stood at Rs 389 crore last fiscal, they were sown from Rs 590 crore the year before.

Zomato has since launched its cloud kitchen vertical, where the company provides the space and sets up the physical kitchen for participating restaurants, who just have to get the food made and fulfil deliveries.

Entrepreneurial organisations keep pushing the envelope, and we want to think that we are one such organisation… Already, at Zomato what sets us apart is that we are a one stop for everything - discovering places, looking up restaurant information, ordering food, booking tables - with more coming up,” Deepinder says.

Zomato is also focusing on increasing its repeat user rate by launching subscription products. Zomato Treats was launched in India earlier this year and gives members free desserts with each order placed at a partner restaurant.

Deepinder says Treats already has 35,000 member subscriptions. The company has also launched Gold, a premium service that gives diners special privileges at top restaurants in their city. This service is available in Lisbon and Dubai and will launch in Delhi later this year. Deepinder says the themes for the rest of the year will be curation and social discovery. He is, however, tight lipped about what form these will take.

Another thrust area for Zomato is technology. Zomato has a major advantage over other startups that offer only one service – like ordering. Zomato’s users perform various actions on the site and mobile app, ranging from search to review and booking a table to ordering a meal. It has more data points on a user.

Deepinder admits that Zomato’s machine learning engines are nascent but based on user data are already personalising the service. This personalisation will only improve in the months and years ahead.

“In fact, at Zomato, our focus through the last two years has been to drive growth sustainably through technology,” Deepinder says.

Freshmenu’s Rashmi is also betting on increased personalisation.

We are moving to Freshmenu 2.0. We will become a smarter food company and put the data we have to work. We will have a more personalised app. The consumer should feel like we know exactly what she wants,” Rashmi says.

She points out a few reasons why her Bengaluru-based startup has seen consistent growth. She says they did hundreds of small things right, like opting for a daily changing menu that ensured the customers kept coming back to check what’s new, focusing on international cuisine, hitting the pricing sweet spot of between Rs 200 and Rs 250 and owning the kitchen and the delivery.

“We are the Zara of food. We give you the food as soon as it gets on trend,” says Rashmi, whose startup fulfils about 12,000 orders a day.

FreshtoHome is in a space very different from Zomato and Freshmenu. It home delivers fresh, chemical-free seafood and meat in Bengaluru, Delhi-NCR, Chennai, Trivandrum, Cochin and Trisshur. The company, which delivers seven tonnes of products a day and has an active monthly user base of around 1.25 lakh people, will soon launch in Dubai and Mumbai. The company decided to start with this category instead of fruits and vegetables due to the higher average order value, which is around Rs 600. The company also owns the supply chain end-to-end and goes directly to the source.

It has created a WhatsApp-like intuitive interface through which it auctions orders to fishermen every day. Depending on who bids the lowest the system automatically assigns them the orders. FreshtoHome then picks up the orders, cleans and processes the produce and then ships to the final markets. Shan says typically seafood sees a 60 percent markup in the wet markets as a number of middlemen are involved.

“Since we source in large quantities and procure directly, we can floor the prices and pass on the savings to our customers,” says Shan, who was earlier India country manager of gaming company Zynga.

Shan’s Co-founder Mathew Joseph is a seafood exporter and had in-depth knowledge on the procurement and processing side of the business. But it still took FreshtoHome two years to set up the supply chain and build up the network of suppliers. For poultry Freshto Home works with a select set of farms. Its Bengaluru centre is already Ebitda positive.

Now, Shan is all set to replicate this model in the fresh fruits and vegetables category. The beta test for Bengaluru market will start soon.

“Foodtech shouldn’t be last-mile sourcing. You need to build real sourcing strength. Only then can you build a defensible moat for the business,” Shan says.