The art and science of facilitation: 6 steps to promote effective collaboration

This book provides principles and examples for successful facilitation in large organisations, industry groups, and innovation networks.

Facilitation is a key activity and skill across the board, in large companies, industry associations, startup networks, international conferences, special interest groups, policy advocacy movements, and non-profit organisations. The 140-page book Facilitating Collaboration offers useful frameworks, checklists, and stories for effective facilitators, and has been authored by Brandon Klein and Dan Newman.

Brandon Klein has been facilitating groups of people to effect change for over 20 years, He is a partner at Difference Consulting and Co-founder of Collaboration.ai. Dan Newman is a partner in Matter Group, and member of the Value Web.

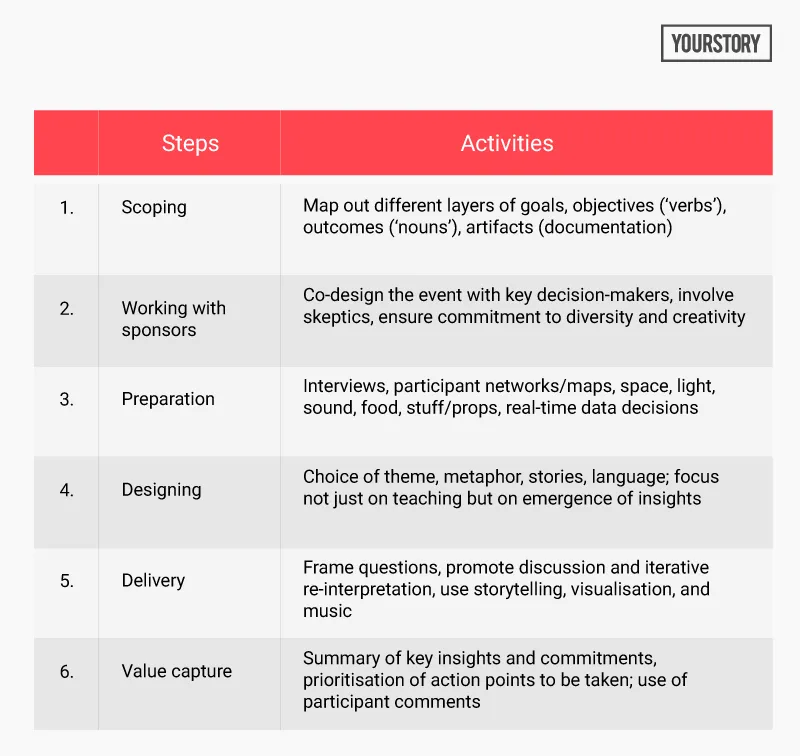

The book draws on frameworks such as MG Taylor’s Design Shop methodology. Case studies are provided from facilitation at the World Economic Forum, Arab League, Cisco, HSBC, and the healthcare industry. I have summarised the key principles in Table 1 below; the nine chapters make for an informative and useful read.

Foundations

Effective facilitation is built by convening the right people, managing the event ecosystem, providing useful content, harnessing data in real time, designing creative activities, and capturing insights via methods like graphic illustrations.

The core skills of a facilitator are listening, storytelling, and problem-solving; years of experience will surface other skills unique to that facilitator. See also my reviews of the related books Multiplier, Let the Story do the Work, and The Storyteller’s Secret.

The facilitator role is a combination of catalyst, conductor, explorer, and disruptor. Facilitators should be proficient in sensing energy and guiding conversations through a judicious mix of “focus, adrenaline, and stream of consciousness.” They should be able to actively listen to participants and also get them to listen to one another.

“The facilitator is the rock protruding from the stream, creating eddies, cross-currents, and rapids while at the same time offering a foothold to whomever wants to cross the stream,” the authors poetically describe.

In a successful event, participants will remember not just the outcome but also the experience. But facilitators should be prepared for a roller-coaster ride of emotions during the activity: confusion, fear, anger, disappointment, fun, joy, frustration and exhilaration. Political tussles with the sponsors may also occur before and during the event.

Scoping

The most important step in facilitation is setting the event scope, which includes objectives and outcomes. This can include, for example, developing a credible go-to-market strategy for a new product.

A good way to visualise the outcome is to write down what the sections of the Executive Summary may look like. It is also important to discuss what will not be brought up at the event, and what are possible extensions of the event duration (eg. working till late at night to work out difficult clauses in an agreement).

There are many layers of objectives, including hidden ones (eg. establishing the credibility of a new manager). Outcomes can be plans, vision statements, decisions, product specifications, and the like. Deliverables are the artifacts created during the event, eg. posters, websites.

Discussions should be planned in such a way that some include prior writing down of points and then discussing them openly (to avoid bias from the first few speakers), while others involve directly addressing the subject. Structured sharing can change the nature and direction of the dialogue.

Working with sponsors

The event should involve a mix of decision-makers, domain experts, and implementers. For example, this can span board members, sponsors, lawyers, HR, financiers and entrepreneurs. Having a diverse mix helps with creative dialogue, and also ensures buy-in to the decisions made at the event.

Some participants can be difficult and even hostile (“snipers” or “terrorists”), especially during times of change; the event can become like an inquisition rather than collaboration. Such people can be sidelined by giving them other activities to do. “A good facilitator always needs to be ready to accept the blame for anything – even the weather,” the authors joke.

Good sponsors will help co-design the event, and serve as the facilitator’s eyes and ears during the event to provide insights that the facilitator team may have missed. In turn, good sponsors will be willing to let the facilitator take the event to new frontiers via iteration and recursion, and also accept criticism from the facilitator if the sponsor’s expectations are unrealistic.

Preparation

In addition to desk research, the facilitator must invest in “face time” – extensive rounds of interviews with a wide range of stakeholders. This helps build multiple layers of perspectives, network maps of relationships, and identification of influencers.

Such preparation can help deal with institutional rivalries, distrust, political agendas, and knowledge gaps. Appropriate reading materials can be designed, and extroverted participants identified in advance. Preparation also includes selection of knowledge objects during the event, such as photos, facts, illustrations and diagrams.

Event environment considerations should cover space, light, sound, food and “stuff.” Natural light works well, as well as ambient music and healthy food (fruits, vegetables). “Stuff” includes everything from flip-charts and panels to creative crockery and plants.

“Keep everyone together. Keep the plenary and the break-outs in the same room,” the authors advise. A data analyst is also useful during large events for accelerated knowledge transfer and effective networking.

Designing

The event can have an overall theme, eg. ecosystems, Mission Impossible, transformers. Themes should be approached in an iterative and recursive manner to allow participants to see multiple perspectives and arrive at unexpected insights and linkages. The physical and psychic space of the event should help with flow of ideas and even embrace “elegant ambiguity”.

Metaphors, stories, and choice of language help guide the discussion in the desired directions. For some events, the aim is not direct teaching but the emerging of learning and breakthroughs via discussion and collaboration. “We put knowledge in their way and let them stumble over it. We don’t teach,” the authors explain.

Delivery

During the event, facilitators engage in a mix of storytelling, guiding, commenting, listening, and promoting conversations around the room. They use stories that effectively act as a microscope, telescope or the naked eye at different stages, to shift perspectives and actions.

Visual facilitation to create new mental models can use giant process maps or interactive animations. Terminology and jargon should be standardised. Facilitators should judiciously strike the balance between focus and divergence during the discussion. Participants should be encouraged to listen actively; “listening is not waiting to speak,” the authors joke.

The advantage that facilitators have is the objectivity of being outside the system; in contrast, consultants are on the edge of the system. Facilitators can thus ask “stupid questions” that may actually surface participant assumptions and blocks, and guide the conversation to desired directions, the authors write.

Music also helps set the tone during moments of transition, eg. when something big is about to happen, or when participant activity is beginning. The authors use covers, re-mixes, jazz and classical music. Music helps overcome awkward silences, and builds energy. “Music moves us all, so we use music to move our participants,” the authors explain.

Value capture

“The best of intentions at the end of a successful event are no match for the inertia that the participants face on Monday morning,” the authors write. Facilitators should capture key takeaways and commitments for the follow-up, and filter out the signal from the noise.

It helps to use the participants’ own words in the action items to be taken. A short satisfaction survey can also be held at the end of the event,

“The days immediately following our events are critical to ensure that they represent a true inflection point rather than an interruption,” the authors explain. Sponsors should decide on the key insights and high impact actions to be executed.

The book ends with personal reflections by the authors on what satisfaction means to them as facilitators. They also describe some of their memorable event venues, such as the tops of New York skyscrapers, the Atlanta Aquarium, and even the Great Wall of China.

Trends to watch during facilitation at large events are the use of analytics and artificial intelligence (AI). They can be used in real time to design activities like networking and break-out sessions, sentiment analysis, and extraction of actionable patterns.