The charging conundrum: What will win the consumer? Charging or Swapping?

Deck: “It’s not only about changing times but also about changing expectations.”

The world is moving towards electric mobility. Governments are coming out with ambitious targets, companies are investing in technology and capabilities, newer businesses are looking for a share of the pie and organisations are publishing reports that prove the rationality of this inevitable shift.

Although facts and figures suggest the increasing adoption of battery-powered automobiles, the concern about a feasible way to distribute energy to these devices lingers around. The real question to ask is - how can companies box a commercially viable proposal and establish a competitive advantage in this non-existent yet booming market? To answer this question, let’s see how the two ways to charge an EV - charging station and swapping station - fare in the future mobility scenario.

Customer experience

Today’s market is very dynamic with the customer being the actual king. The product or service needs to appeal to the customer and clearly display the benefits over the previous commodity. If the proposal lacks an answer to why the product will really benefit the customer, the efforts are most likely to reap unfavourable outcomes.

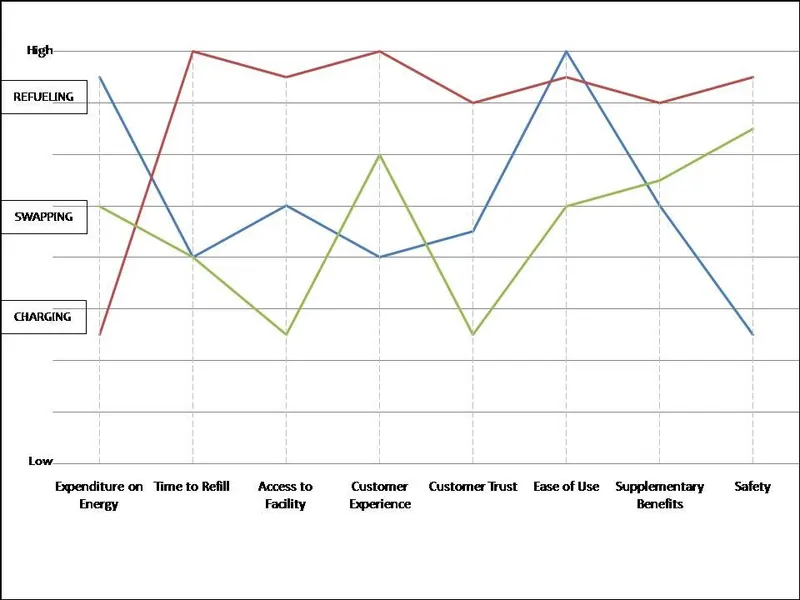

To explain this further, a canvas is given below that attempts to compare refuelling, charging and swapping on the lines of factors most crucial to the consumer experience. The horizontal axis captures the range of factors and vertical axis captures the intensity of the focus of the factor.

Comparing refuelling, charging and swapping capabilities, we can see that charging outperforms almost all the customer experience factors, leaving time as the only major disadvantage. Spending time on charging is not a disadvantage for many due to access to charging points at various locations, including residential vicinities, which is not possible in the case of refuelling and swapping. Also, trust with swappable batteries is minimal in a country like India, which faces issues of theft on a routine basis. The creation of supplementary benefits and safety by charging technology might become its unique selling proposal in the times to come. Finally, the customer is the final decider. If one closely examines the changing expectations, a requirement of a distribution that offers better flexibility will be observed.

Refuelling time

A trip to the petrol bunk ideally takes around two to three minutes today. With electric vehicles coming in, the time has changed. A swapping station, without human intervention, takes about two to five minutes, while a plug-in charging facility with a type 1 & 2 takes around two to six hours and type 3 takes 10 minutes to two hours.

The charging requirements vary with vehicle landscape. A taxi aggregator or a fleet owner operating at high capacity clearly values swapping overcharging, but for a two-wheeler rider or a car owner, it’s the opposite. This is because for a majority of passengers on road (74 percent), intra-city or last-mile travel is the requirement that is limited to 5-40 km/day. Visualising the bigger picture, both the facilities seem essential, but the scope really depends on how the buyer perceives it.

Ease of use

At a petrol bunk, fuel is bought keeping in mind the requirements of the trip and spending capacity. Intra-city passengers are given the freedom to choose what they require. Charging stations will function on similar lines. Moreover, charging points at homes, offices, cafes, malls, etc., will create an additional sense of ease of use for the consumers, eliminating the need to visit a charging station.

In case of a swapping station, the flexibility of choice is not widely explored. Moreover, it becomes inefficient for operators to tailor-make the battery charging levels due to infrastructural barriers. For the inter-city travel, swapping finds a great fit into the plot, cutting down travel time to appreciable grade. But the ease of use is still a bargain.

Freedom of design

To swap a battery from a vehicle, the design must allow certain considerations in the structure that ensures easy deportation and reattachment of the battery pack with the body. This feature in your car will eventually limit freedom to design the vehicle and customise it to an undeniable limit. As time progresses, aesthetics and construction will gain a bigger share of consumer requirements and with a slight limitation of ideation, compromises are imminent.

Standardisation intricacy

To access the swapping station, one needs to have a standardised battery pack, i.e., the battery used in the vehicle must have similar architecture. Not only does this setup seem impossible when comparing CV with PV, 3W & 2W, but it is also very difficult for two rivals in the CV space to have similar designs, which evidently cut down their competitive advantage and innovation capabilities.

Companies like Tesla and Better Place have tried a good hand at comprehending swapping infrastructure, but the efforts have been frivolous due to the low adaptability from the consumer segment. Moreover, if the framework was essential to adopt, the main dilemma that vehicle manufacturers would face would be to keep a similar battery dimension for all their models. Charging, on the other hand, also requires standardisation, but to an extent of adapters that connect the charging plug to the vehicle. This apparently looks workable.

Cost of infrastructure

The swapping station operators must ensure the number of batteries to recharge, and which battery to accept. The operators find it extremely arduous to plan the answers to these two questions. Firstly, car owners with different battery degradation levels visit the operator for a swap. It is very difficult to interpret the real time condition of the battery on the basis of which the new battery will be swapped. Secondly, if the switch takes place between different or competing operators, establishing an intermediate system to retain a battery becomes a challenge which increases costs to disproportionate levels.

If this cost was to be included in the subscription model of the driver, the vindication of the cost seems painful because of the lack of real-time monitoring of the condition of batteries received and batteries given for every vehicle. Also, the surety of the exact same car visiting the station every time is hard to find.

Cost of ownership

In the charging scenario, you own your car’s battery. But in a swapping scheme, you can either own one or not own one. If you own a battery, then you need to have at least two batteries - one for powering the vehicle and one which will get charged at the swapping station, cutting down the benefits of a swapping station making your EV more expensive.

If you let the swapping operator own your battery, it makes your EV cost somewhere closer to the petrol variant. But the price a customer pays for the energy will include the maintenance costs of the battery. Again, the cost of degradation of battery is unknown and eventually, the subscription costs will include cost of two batteries with swapping costs, making the entire need to own an EV a gimmick. This can be avoided in the case of charging points which lets you pay for the electricity your battery uses.

Finally, energy distribution infrastructure will boom as time advances and both battery charging and swapping will be given their due preference. Standardisation and fast charging will become mainstream. The charging conundrum will then shift from adoption to optimisation and synchronisation of the already built. However, as expressed, the customer needs to find real value in the proposal. It’s not only about changing times but also about changing expectations.

(Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of YourStory.)