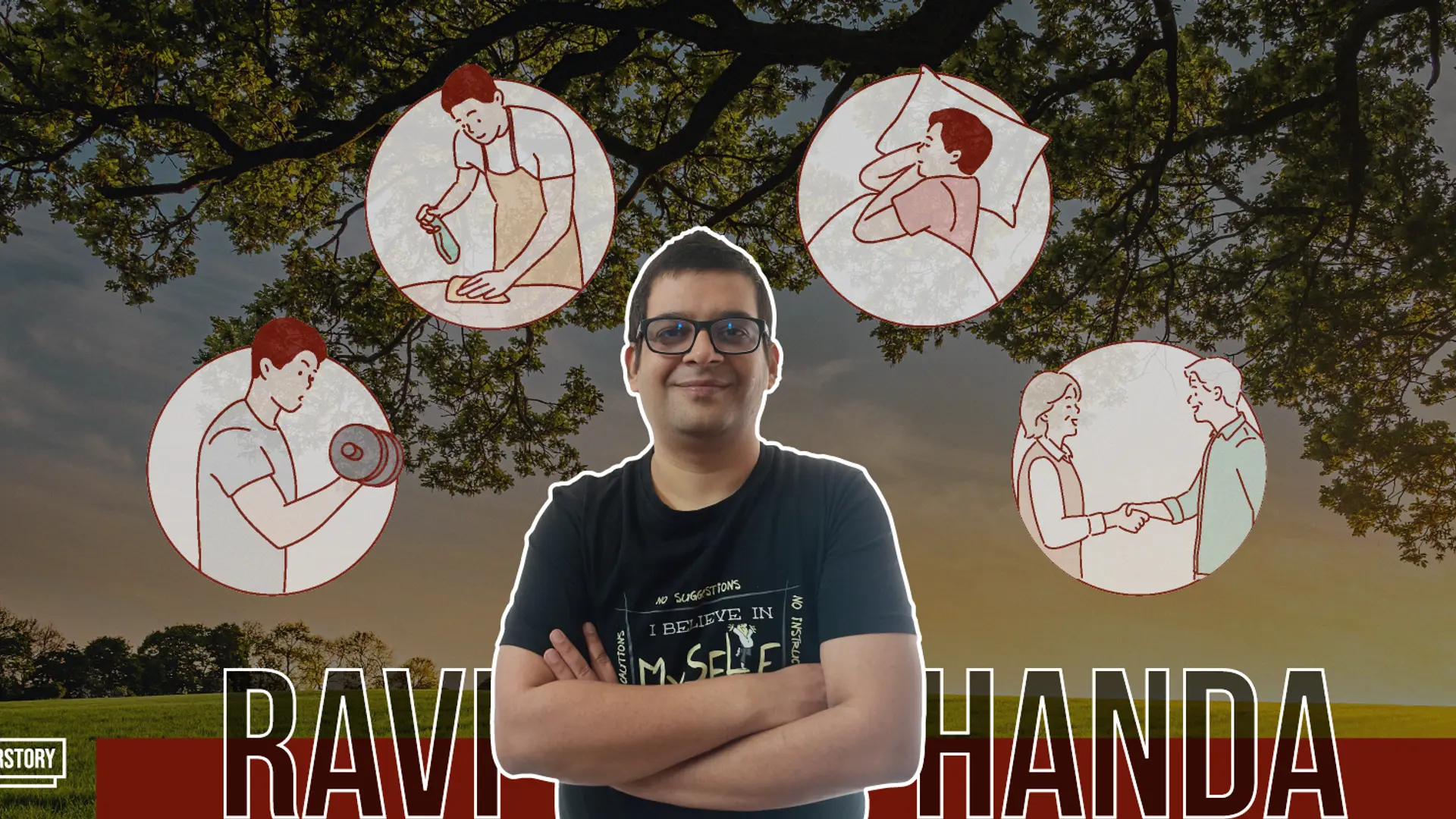

Meet the (ex) edtech founder who won’t hustle

Ravi Handa belies the archetype of a successful entrepreneur who ran an edtech startup for eight years before selling it to a bigger fish, Unacademy, and joining its school. He quit from there, too, recently, and now plans to live.

For someone who was in the market for a fitness band that could get him pushing harder, all that this former startup entrepreneur wants to do is stop running.

Ravi Handa, by all means, is a successful edtech founder going by the celebrated yardstick of an exit by sale. Now that he’s also exited , which had last year acquired his cheekily named online learning platform, , he’s actively scouting for a job.

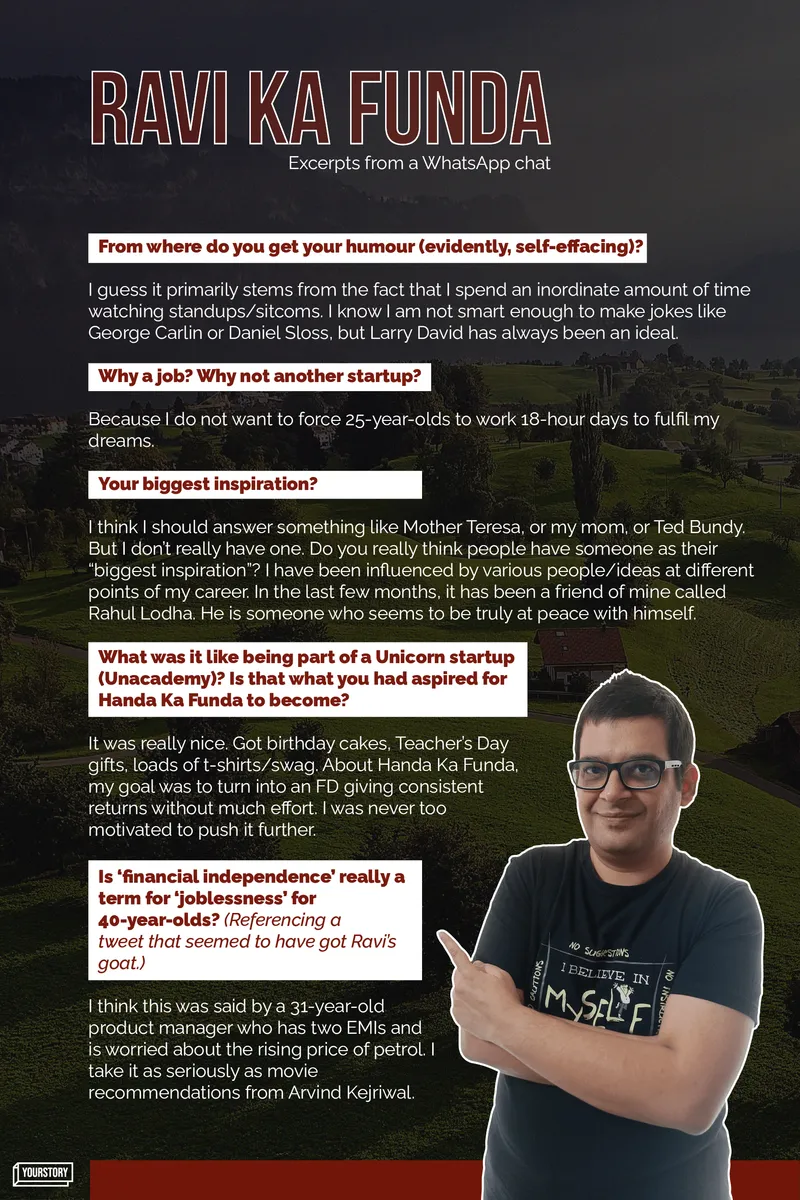

Not any kind of job. He’s quite picky, and here’s his pitch: “Ideally, I am looking for a job where I do not have to do anything and still get paid a lot.”

That ideal doesn’t exist, though. Definitely not in an overzealous startup universe where ‘hustler’ is a badge of honour and founders are rooting for 18-hour work days. And he knows it.

By Ravi’s own admission, it’s the first time in his career that he’s in a situation with no clarity. But he’s certain about this: “The only thing I know is that I do not want something full-time. For now, my priority is to be time-free.”

It’s an interesting concept—to be time-free—and Ravi gets into the details of it. But it’s not something you often hear escaping the pursed lips of startup entrepreneurs. Particularly not from someone who’s made it through the prized gates of IIT-Kharagpur, and with a dual degree to boot—BTech and MTech in Computer Science and Engineering.

Hustling, for long almost a clannish mantra in startup circles, has been getting a bad rep lately. Relentless grind and ploughing through meeting after meeting and iteration after iteration is almost an inevitability for most founders.

Startup employees embraced a ‘work hard, play harder’ culture. The ‘play harder’ part ground to a halt during the Covid curfews. And as companies worked harder to survive, the successes borne out of those efforts got glorified.

Then the virus ebbed, and the intensity of that phase soon regressed to burnouts, the great resignation, and quiet quitting.

A few startup founders who sought to revive the hustle through what in their heads might have seemed like motivational social media posts, had to run for cover as they got hounded by a generation exhausted from being pushed hard at work.

And yet, as Jasdeep Mago points out, hustling in its toxic form is also often self-inflicted, with many individuals on their own pursuing multiple ambitions—“one active, one passive, and one passion project”. Jasdeep is the Co-founder and CEO of Invisible Illness India, a mental health startup with a focus on workplaces.

“Everyone I know has three streams of income. I don’t know a single person who just goes for the 9-5 and goes home and just chills,” she says over a phone interview. “And that is what hustle culture truly is—the need to utilise every second of your time to prove that you are somebody.”

In the office, this manifests as companies valuing individuals only for their work, and not for the person they are, Jasdeep says.

She does have a good word for startups, though. Several young companies are changing the narrative by not just pushing numbers but also engaging their employees in multiple ways and celebrating the impact they have on the company as a whole.

“Like when a crisis occurs, people get a different purpose. It’s not just, oh, I do sales, but it’s also when there was a crisis, we managed it all together. Then it’s like, I’m not just these numbers, I’m more than that.”

Ravi, nearing 40, and the son of government doctors with transferable jobs, believes the hustle in startup culture arises mostly because people are grossly overpaid, counting himself among those who were.

“Once you overpay people and everyone around you is overpaid, then the expectation is that, okay, everyone is a superstar, hardworking performer… And once working for 12 hours a day becomes the norm, it’s a problem.”

Trust Ravi, quite the funny man and a Larry David enthusiast, to flesh out the absurd to illustrate his point.

“I can tell you the example of a friend of mine who spent a week or 10 days in Bali (when offices were still shut), saying he was still in his Bengaluru home and working. And this is the Founder-CEO of a reasonably well-funded company. No one in his office knew this bugger was in Bali and working from there,” Ravi says, visibly relishing the anecdote over a brief Zoom interview.

“At the end of the day, you have to have some way to motivate a large number of people. I understand they need to do that. (But) I also believe that some of them overdo it.”

Ravi speaks from his experience as a founder who was able to run Handa Ka Funda for eight years with minimum hustle (the team at its largest had 12 people).

“I do believe that if you give people a certain amount of freedom… they will do a good enough job to justify their salary... I believe that’s good enough.”

Ravi’s take isn’t necessarily a knock on hustling. After all, shortly after he tweeted seeking recommendations for a smartwatch to help improve his fitness, Vishal Gondal, Founder-CEO of GOQii, hustled and jumped into the conversation to pitch his fitness startup’s smartwatches. (A ‘talk’ was agreed on for the following day, and a watch was obtained.)

Rather, Ravi’s priorities seem long-entrenched, from even before his startup days. Following graduation in 2006, he decided not to take up a job in computer science.

“In college, I realised that the people doing Computer Science Engineering were smart and hardworking. I realised it was going to be a hard job to do… (But) teaching was something that came naturally to me, or maybe it didn’t seem very difficult.”

So he took to teaching with IMS Learning Resources, training students for entrance tests to premier management degree programmes, including the Common Admission Test administered by the Indian Institutes of Management.

A few years down, he hit a ceiling. There was more money to be made helping kids prepare for tests to engineering courses. So it was either switch to that or move to the business side of things—in a managerial role or by starting his own test-prep institute.

Instead, he chose to fall back on his engineering degree and joined sales enablement startup MindTickle in Pune.

Meanwhile, Ravi had been publishing video tutorials on YouTube, both for IMS and on his own. While he didn’t see significant traction on those, it was a useful skill. Soon, he was pitching it to small institutes and began making YouTube videos for them, earning a fair bit.

“That’s when I realised that if other people are paying (for my videos), I should start making those for myself. And the margins were pretty good.”

Ravi founded Handa Ka Funda in 2013. Around then, he also met Gaurav Munjal with a proposal to make coaching videos for him. Gaurav’s Unacademy would formally come into existence two years later.

Handa Ka Funda fared well, peaking in 2016 as Reliance Jio’s rock-bottom prices for mobile and data services got more people using the internet. “Revenues climbed up and everything was going great. But with easy access to the internet came a lot of content creators.”

The edtech sector was also picking up, with investors flocking to tech-driven startups. And when Covid struck, even traditional classroom-focused coaching centres went online. (A different matter now that edtech companies are going the classroom route.)

Ravi had three options: pivot to an edtech company and raise funds (“but too much work would be involved in that”), let the business run till it would eventually shutter, or sell.

So after eight years of running Handa Ka Funda, mostly from Jaipur, Rajasthan, Ravi sold his startup to Unacademy in March 2021 for an undisclosed sum. It was a good deal, not only because it made Ravi financially secure but also allowed him to focus on just teaching at Unacademy.

But that too involved certain commitments. He was required to take about 80 live online classes every month, which meant preparing and scheduling the classes well in advance, so his students could be prepared.

That meant a lot of preparation for him as well. And “because these were live classes, much more than the work, it is also about not having freedom of time,” he says. “Earlier, my schedule was not predefined or preset.”

And so, earlier this month, Ravi exited Unacademy. He could now be “time-free”.

“There are plenty of things that everyone wants to do in their lives. But the three major concerns are whether their health allows for those or not, whether their finances allow for those or not, or whether they have the time to do those or not,” he says. “I have the money to do most of the things that I want to do. But I never had the luxury of time.”

Ravi’s big inspiration presently is a friend from college named Rahul Lodha, a former Chief Technology Officer at Aakash EduTech Pvt. Ltd. who now runs Urveera Sustainable Learning and Development at Chakulia in Jharkhand.

“When other friends are sharing pictures of either them drinking or travelling, he’s sharing pictures of a tree and asking us to find the snake in it,” says Ravi. “He seems to be devoid of any struggles that I have or I see my friends have. He is beyond that.”

For now, Ravi’s not looking to startup, or even take up a full-time job—viewing both options as extremely demanding and bearing much responsibility. He’s up for part-time assignments, though, at least for a year or so.

Until then, he’s content channelling his inner Larry David: “People do tend to have a lot of expectations (of me). And I have been ruining expectations for a very long time.”

Edited by Suman Singh