The wisdom of the crowds: can it beat or match experts?

In India, the concept of harnessing ‘the wisdom of the crowds’ to predict the results of certain events is relatively new. Still, India’s crowdsourcing advisory firm CrowdWisdom is proving that a group of people can come together and beat or match experts in predicting the outcome of future events.

The start of the year has always been the time for expert predictions on news, events, and trends for the year ahead. This year is no exception, especially with the upcoming Lok Sabha elections, for which pundits and experts are already weighing in on which party is set to win the people’s vote. And yet, if the past has taught us anything, it’s that expert opinions and polls don’t always reflect in the results. Just as was the case in the recently concluded Legislative Assembly elections in some key states in India.

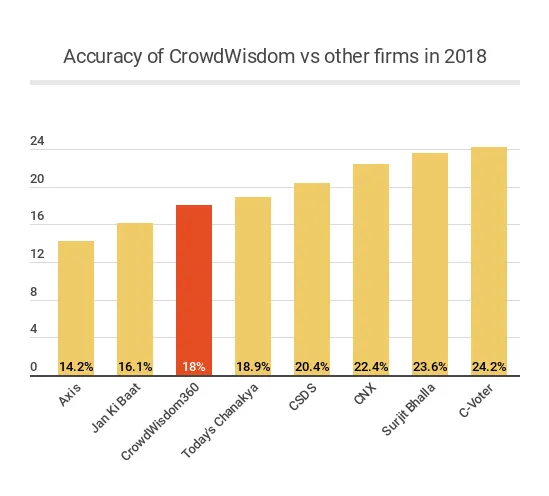

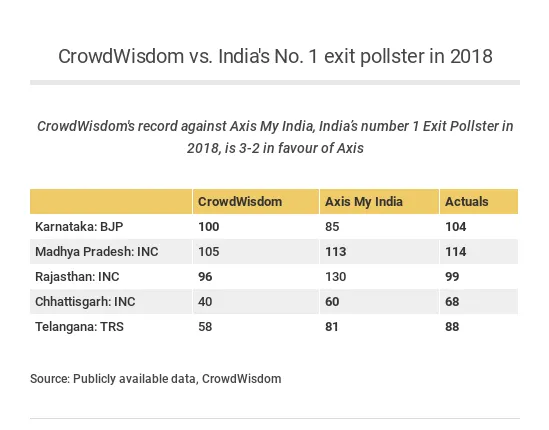

Interestingly, at the end of those elections, CrowdWisdom- a crowdsourcing based advisory firm, ranked third out of eight polling firms, behind Axis and Today’s Chanakya - outperformed established names like C-Voter, CSDS, Jan Ki Baat, and Surjit Bhalla.

Over the past 12 months, CrowdWisdom’s crowdsourced predictions have repeatedly outperformed or matched that of many experienced players for a range of events, including elections, economy, sports, terror attacks and movies. For instance, CrowdWisdom beat polling gurus like Surjit Bhalla to predict Assembly elections in India, they also managed to predict the Pakistani and Brazilian elections fairly accurately, and deliver GDP forecasts on par with companies like Bloomberg and Reuters.

Still, conceptually it’s difficult to fathom how a group of people beat or match experts, as CrowdWisdom works to harness the ‘wisdom of the crowds’ to predict the future.

In other words, CrowdWisdom works on the premise that large groups are collectively smarter than individuals, including experts.

Watch this video of the BBC's The Code Series for more on the concept of crowd wisdom.

How crowd wisdom works?

While there is enough published research on this topic, particularly with examples from the West, this is a relatively new or emerging area in India. So, how does the crowd actually go about predicting the results?

There are two crucial elements to how every individual in the crowd goes about predicting the results of an event: anchor point and psychological/mindset.

A study of the different participants on CrowdWisdom for over a year showed that they displayed consistent behaviours. While some participants were consistently middling and conservative, others were constantly gung ho. This was true in most, if not all, events.

The second element in predicting the results is the anchor point, which is an opinion based on a variety of factors such as past results, opinion polls, discussions with friends and family, and perhaps even sheer gut. For example, an anchor point would be a clear knowledge that a World Cup final is unlikely to have more than 3 goals, or that a party in Lok Sabha elections is unlikely to win more than 350 seats or less than 150 seats.

Source: CrowdWisdom; publicly available data: news sources, Wiki

Once the two ends of the anchor points are defined, the psychological mindset comes into play. The more optimistic users align with the upper end of the range and the more conservative ones with the middle. When the participants represent a variety of team/party supporters, the outcome is a wide variety of results that tend to eventually add up to an accurate average.

However, all hell breaks loose if only one side is represented. The less diverse a crowd, the higher the likelihood of getting an incorrect prediction.

Why crowd wisdom beats or matches experts

To understand how the predictions made by a crowd is able to match or exceed that of experts, it is important to take into account other factors that determine the result. These include interest in and familiarity with the subject, risk taking, reach, and reward, among others.

Interest in the subject

Participating in the wisdom of the crowd events is voluntary. As such, every time a large number of people interested in a topic is approached for participating in a wisdom of the crowd event, not more than two to three percent actually volunteer to participate in it. So, the crowd is really not so big in terms of penetration. However, since they represent the general population, they tend to be of large volumes anyway.

The low participation levels indicate that only those who are most interested and fairly confident about a subject are most likely to participate in an event.

Therefore, while crowds are not necessarily trained on a given topic, they have a certain kind of intimacy and interest that others in the general population lack. This provides access to a wide body of information given the sheer volumes and the depth of intimacy of every single member of that crowd with some or all elements of the topic.

Take the example of the Pakistan election. The crowd came from all parts of Pakistan. But the crowd from Lahore was particularly important because if there appeared to be momentum in favour of PTI in the stronghold of PML(N), it would mean a national wave towards PTI. Being on the ground and talking to other voters, the crowd is able to better pick up such trends that many experts would otherwise miss. Also, as individuals, we are more likely to be honest with our friends than with an opinion pollster.

During the Karnataka elections too, CrowdWisdom found the crowd on the ground to be more sensitive in their predictions as opposed to those who lived outside the state. So, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi was campaigning in Karnataka, it took some time for the crowd outside the state to figure out the impact of Modi’s campaign at the ground level.

Comfort with the subject

Prediction events are not simple. While there is a reward at the end of it all, there is some degree of effort needed to get the tallies in place. The possibility of rankings and others becoming aware of one’s performance are also big factors in who chooses to predict. Therefore, those who finally choose to predict are the ones who are most comfortable with the topic and quite confident of their subject matter expertise.

So, contrary to the general belief that the crowd is not very knowledgeable, the fact is that only the most knowledgeable participate in CrowdWisdom predictions and generally tend to be well informed, given the sheer availability of high-quality information today. Subject matter expertise might be still be an advantage for an expert, but only a little.

However, there is always a variance in the level of comfort the crowd has based on participation levels, in that individuals who appear to be quite comfortable with predicting an event related to say Uttar Pradesh, would display relatively lower levels of comfort with doing the same for other Indian states like Telangana or even Chhattisgarh.

Similarly, individuals who are very comfortable with predicting an event for Andhra Pradesh may not be so with Maharashtra. In other words, while we can always gather a crowd for a prediction, the crowd is not the same. In each case, the crowd is unique to that event and has a certain level of comfort and confidence with the prediction event at hand.

Reach/scalability of the crowd

Whether it is related to the economy or elections, reach matters a lot.

While the expert is usually reliant on published data from the government and the private sector, the crowd would look around and talk to others in the neighbourhood, in addition to searching for information online.

That’s why, when a crowd of 700 people participate in a prediction event, that count would actually be seen as a representative of 7,000 observations. This is because the crowd is actually much larger than just the actual number of participants. The crowd has a much larger reach and is often directly able to see of what is going on at the ground level.

For example, when the economy is weakening, the crowd would know it first because they see this unfolding with their jobs, with their friends, or even in their neighbourhood.

Take another example: in Karnataka, CrowdWisdom’s rivals reached out to 15,000 voters, while CrowdWisdom reached out to 800 savvy forecasters whose eyes and ears were constantly on the ground. While each individual forecast may not have been perfect, the sum total outcome added up to a massive amount of wisdom leading to more accurate results.

Risk taking

There is no published data on risk taking by experts, but it’s only likely that this level is much lower than that of the population. What is intriguing is that CrowdWisdom’s participants rarely replicate opinion poll data even when the opinion poll data is from an expert. There is a tendency to go by self-belief, based on past experiences, rather than trust an ‘expert’.

Experts, on the other hand, rely on data that may or may not be the most accurate and sometimes miss key nuances.

However, a higher number of participants on CrowdWisdom are likely to push the envelope on the different possibilities, thereby, giving a wider range of datasets, that, in turn, takes the average closer to reality.

When the predictions are laid down as a curve, it does not follow a typical normal distribution curve; instead, there is a much more even loading, with a bias on the two ends or two peaks if you will. One could argue that this is a function of biases but it is, in reality, individuals sharing their perspective. If they did not take the risk of doing this and instead aligned to the average or some opinion poll, the results would have been quite inaccurate.

Trusting one’s own instinct and taking a bigger risk than expected is more likely to generate the correct or desired result.

Law of averages

The biggest difference between experts and the crowd is that, since the expert group is made up of a small number of people compared to the crowd the crowd is naturally more diverse and perhaps more reflective of the population in general.

The crowd’s law of averages, therefore, dictates that more often than not, the average of the crowd tends to come close to the actual performance.

In many ways, the crowd behaves like a sample survey. Except that, in this case, a smaller group of people yields the desired outcome because the crowd possesses more expertise than the average person on the ground. The accuracy improves as more people participate in these predictions. But beyond a point, the averages do not change substantially.

The Karnataka election averages remained the same for about a month before the election, although 70 percent of the participants joined CrowdWisdom during the prediction event. Further, not more than five percent were within five percent of the average prediction.

Group interactions

Social media has become a big enabler for interactions within group interactions, and even perhaps outside the group.

Every day, participants scroll through their social media feed to keep themselves abreast of the latest event. They visit public forums, read through other people’s comments, visit websites like CrowdWisdom, and read about opinion polls.

Here, they interact with others, argue, debate and consider or reject other people’s opinions. Any dissonance definitely impacts their thinking and any reinforcement solidifies their opinion. But at the end, these interactions with other users enhances their knowledge of the issue at hand and hence enables them to make wiser predictions.

Reward

Reward is a very important driver.

The higher the reward, the lower the variance in the predictions. By offering rewards for accurate predictions, users are motivated to do some research on the subject and likely to make less outlandish predictions.

Whether it increases group accuracy substantially is difficult to say but it does eliminate the number of outliers in the group.

Difficulty in prediction

Another important factor to note is that the more difficult it is to enter prediction information, the more feasible it is for platforms like CrowdWisdom to eliminate less serious participants. While this is not the purpose, it certainly ensures honesty, as only people with basic knowledge participate. In fact, while thousands visit the CrowdWisdom website every day, only a very small, percentage venture to predict an outcome.

Does the crowd get it wrong?

It is not all hunky dory. The crowd gets it wrong sometimes. One place where the crowd gets it all wrong is when all the participants have their emotions tied to one outcome.

This often happens in sports where everyone hopes that their prediction comes true. It is more of a wish than a fact. It is almost impossible for the crowd to predict accurately in instances where the time to study and come up with an informed choice is less. The greater the time given, the better is prediction made by the crowd.

The crowd is also quite unprepared for sudden turn in events, as many times, such changes, do not necessarily come from the environment in and around them. Some examples could be a terrorist attack on an oil producing country, a great spell of 10 overs, a new technology invention, and so on. It takes time for the crowd to digest such information and come up with accurate predictions.

In addition, there is the issue of anchoring, in that, if the anchor points around them are far off from their own personal experience, many participants would subdue their predictions. Next, would be the reach of the platform, as the crowd has to be diverse to ensure accuracy.

Still, this is an area where talented people in renowned organisations like Stanford University, the CIA and numerous others are creating even more sophisticated models and algorithms to predict the future – something we in India hope to come up with too.

The value of crowd wisdom

So, where can you use the wisdom of the crowd? Almost everywhere.

CrowdWisdom has identified 18 categories and areas where the crowd can be extremely useful and perhaps as reliable as an expert to predict the future. They are: politics, business to business, economy, shares and investments, startups, education, advertising, fashion, movies and entertainment, music, sports, hobbies, careers, relationships, automotive, durables, travel and tourism, and healthcare.

For example, according to Moneycontrol, relatively lowly ranked funds (4 percent return lesser per annum for 5 years) make up about 30 percent about of mid-cap funds. One might ask the question of who owns these funds? Or whether they even worry about their portfolio? Or, more importantly, who advises them?

It would be reasonable to assume that it is a mix of a smart distributor and maybe even friends and family who advises these investors. But this is exactly one example of how crowd wisdom offers tremendous value, as the crowd can advise investors to make wiser choices at almost zero cost.

Going forward, the concept of crowd wisdom is only likely to gain more traction, as its use cases across sectors increase.

The increased adoption of smartphones and high data access will also provide more fuel to the wisdom of the crowd approach. This is especially true in the startup ecosystem, where entrepreneurs test out new technologies and products.

The current method of surveys will increasingly be replaced by the wisdom of the crowd approach which will likely deliver the same or better accuracy, while reducing costs significantly -- an important factor for startups.