How Mission Finland by Hippocampus changed the lives of kids in Indian villages

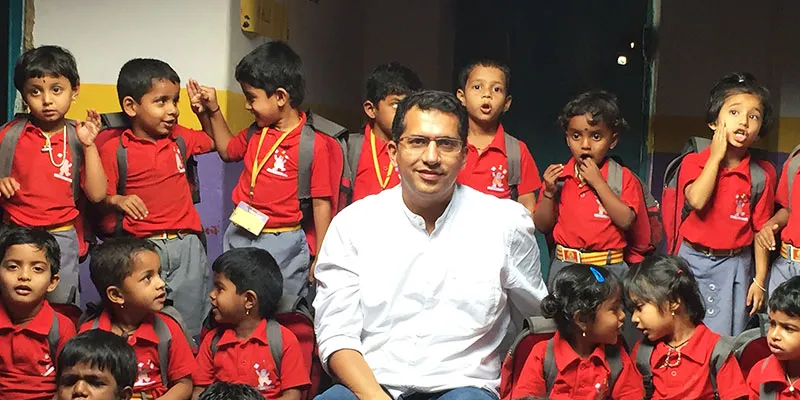

Apathy and indifference in the existing government school setup led to the creation of the Hippocampus Learning Centre. Today, Hippocampus has over 150 preschool centres with 5200 students and 350 teachers. However, only Founder Umesh Malhotra can tell you about the challenges he had to face on that long journey. By 2020, the aim is to bring preschool education to as many students in India as the population of Finland, but at one percent of its cost. That is why it is being called Mission Finland!

Umesh got to know about the Akshara Foundation during a chance conversation with Rohini Nilekani in the Hippocampus library. He went along with her to visit a government- run school in a village and got a cultural shock. “I was appalled by the apathy with which these schools are run and what was being passed off as education in our villages,” says Umesh.

It was the first time Umesh had walked into a slum and the experience shook him to the core. “I had led this really comfortable elite upper middle class life till then; what struck me was the hope with which parents continued to send their kids to school day in and day out even under such pathetic conditions.”

The dimly lit classrooms, open drain right outside the classroom, disinterested teachers and complete chaos stayed in Umesh’s mind. “If you think going to an RTO is painful, put your child in a government school and you will know what pain is,” he says.

The gut wrenching conditions, the indifference and the hopeless environment the parent and child walked into every day was a learning experience for Umesh. “It taught me that human beings live on hope; you would not have a 97 percent enrolment rate if that was not so,” he adds.

Umesh got into the system believing that he could fix the situation. However, one of the biggest challenge he faced was trying to change the mindset of the people who are part of the system. “You do really cool stuff in IT and get paid obnoxiously but you have no idea how much it means to bring about change. I took that step believing I could fix it in a couple of years but I failed,” he admits.

Since Umesh already had a success story in the Hippocampus Library, he though why not replicate the same for kids in government schools and villages. “We felt that no matter how bad the schooling experience was, if we could get the child to interact with books it might change his life, even if only for one hour a week,” he says.

However, the task was not as easy as that. The children were unable to read, teachers didn’t care, the market did not have enough books, the headmaster thought libraries were a waste of time; they didn’t receive help from parents either. “With all these challenges, the task became increasingly difficult. We had to train people on the basics; it was three years of humbling experience. Fortunately, the hope parents had gave us the strength to keep going.”

In 2007, they created ‘Grow by Reading’, a simple library program, which overcame some of their difficulties. The books were categorised according to reading ability; there were six levels. Each level was given a colour like green, red, orange, white, blue or yellow. Every child was put under a reading level according to the assigned colour. “It took us three years of failure to get to this idea. The library books were marked according to the colour and so were the children’s membership cards; each child could go and read level appropriate books,” adds Umesh.

To incentivise the habit of reading, several activities were initiated, like colouring tasks which brought more kids to the library. “When kids came for the activity, we told them they would have to read two books before that and they would enthusiastically go and do some reading. By 2009, we had over 50,000 children enrolled in the program and had moved on to add books in Urdu and Hindi apart from Kannada, English and Tamil,” says Umesh.

Soon Hippocampus was approached by the NGO A Room to Read,. It scaled the programme up to cover nine states in the country and now works in 10 countries too. After becoming an Ashoka Fellow in 2008, Umesh got the opportunity to meet other social entrepreneurs and visit villages across the country. Talking about the incident that gave birth to the Hippocampus preschool learning program, Umesh says, “I was in a village in Chitradurga district when I learnt that there are no preschools in villages. Children were directly being admitted to Class 1 where they were following the state board syllabus, which was the same across the cities and villages. While in cities kids had a chance to learn basic English and math in preschool and could cope with the syllabus, rural kids couldn’t do that and this lead to dropouts . This meant that equal opportunities were not being given even if the syllabus was the same,” says Umesh.

Keeping the focus on rural India and activity based learning , the idea of Hippocampus Preschools came into being with Asian Development Bank as an investor. “We wanted to set up better education and scale for the poor in the country. We wanted to set a benchmark for the bottom five billion in the country,” says Umesh. The Hippocampus Preschools charge parents a fee of Rs 3000 for a year. While several parents pay upfront, others prefer to pay on a monthly basis. “We are replicating the same idea as a ration store; we give you very good quality education at a nominal price,” adds Umesh.

While there have been several challenges like individual driven harassment or government officials creating issues because aanganwadi schools were feeling insecure, the goodwill of parents has kept the team going.

“Teachers in our schools are enjoying teaching now because kids have become more receptive. All our teachers are hired based on a written test, a reference check, check on if they can handle classroom stress and deal with it calmly. We give simulated situations, management interviews are done, an induction training is also carried out where we give them homework. We want to see if we can trust the individual to run a classroom independently. We even train teachers to speak English. As they know the written language and not the spoken one, we use phonetics to teach them the right diction and pronunciation.”

Talking about his experience, Umesh says, “Today when I go back to the schools and see children stringing sentences together, happy with learning and education and well grounded teachers who love their job; it encourages me to do so much more.”