An ode to women writers who questioned authority

The Vedas cry aloud, the Puranas shout;

“No good may come to a woman.”

I was born with a woman’s body

How am I to attain truth?

“They are foolish, seductive, deceptive –

Any connection with a woman is disastrous.”

Bahina says, “If a woman’s body is so harmful,

How in the world will I reach truth?”

– Bahinabai (1628 – 1700)

The literary community of India is witnessing a stir. A generally divided community along ideological and theological grounds seems to have united against a real problem. Among the writers who have returned their awards to stage protest against rising intolerance in our society, two are women. While Shridevi V Aloor has returned the Aralu Sahitya award given by the Karnataka state-run BMTC, the famous English writer Nayantara Sehgal has returned her Sahitya Akademi award. Shashi Deshpande, another author has also resigned from the Sahitya Akademi general council.

While a lot is being debated and discussed, it must be noted that women writers protesting establishment is not a new phenomenon. Being on the receiving end of many social dogmas, it is but natural that women writers have historically used the might of their pen to voice their witty, ironic, poignant inner selves and questioned the authority their families, society, and government have tried to impose on them. While Sule Sankavva wrote as a prostitute in the Bhakti tradition, and startled contemporary sensibility with her sacrilegious writings, modern writers like Mahashweta Devi combined women’s causes with political movements.

India has a proud long history of women writers who questioned dogmas of their times, and were questioned back.We present to you a list of five such women writers, from across India’s historic timeline, who stood up against the establishment of their times and wrote for peace, humanity, and justice. The list by no means is exhaustive, but we hope it starts a meaningful dialogue in the times to come.

Akka Mahadevi (1130–1160)

At a time when spiritual world was primarily dominated by men, Akka Mahadevi earned the term Akka (elder Sister) out of respect given to her by other saints and poets including Basavanna, Siddharama, and Allamaprabhu. Her life and writing challenged the patriarchal dominance of the world at large, as she wandered naked in search of divinity. As one of the early female poets of the Kannada language and a prominent personality in the Veerashaiva Bhakti movement of the 12th century, she frequented in many gatherings and debated philosophy and mysticism. In search for her eternal soul mate, Lord Shiva, she made the animals, flowers, and birds her friends and companions, rejecting family life and worldly attachment.

She is particularly known for her bold feminism. Akka Mahadevi describes her love for Lord Shiva as adulterous, viewing her husband and his parents as impediments to her union with her Lord. She talks about replacing her husband with Shiva, calling her relationship with mortal men as unsatisfactory. In one of her other poems, she expresses the tension of being a wife and a devotee as –

Husband inside, lover outside.

I can’t manage them both.

This world and that other, cannot manage them both.

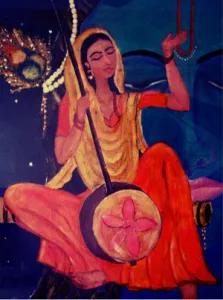

Meera (1498–1547)

The 16th century mystic poetess had fearless disregard for social and family conventions. Treating Krishna as her lover and husband, Meera (Mira Bai) was persecuted by her in-laws for her religious devotion. Although authentic historical accounts on Meera are unavailable, scholars believe that she was well educated in music, religion, politics, and governance. She was married to Bhoj Raj, the crown prince of Mewar, who died in battle, along with her father and father-in-law. According to a popular legend, her in-laws family tried to execute her numerous times but failed, while Meera devoted her life to poetry.At a time deeply rooted patriarchy, Meera wrote love poems where Krishna was the lover, and she was a yogini ready to engage in a spiritual marital bliss. It is believed that she spent a major part of her later life in pilgrimage, “dancing from one village to another village, almost covering the whole of north India.” In one of her poems, she writes –

Mira danced with ankle-bells on her feet.

People said Mira was mad; my mother-in-law

said I ruined the family reputation.

Rana sent me a cup of poison and Mira

drank it laughing.

I dedicated my body and soul at the feet of Hari.

I am thirsty for the nectar of the sight of him.

Mira’s lord is Giridhar Nagar; I will

come for refuge to him.

(Source : PoemHunter)

Sarojini Naidu (1879–1949)

Known as the Nightingale of India, Sarojini Naidu was an intellectual way ahead of her time. Not only was she the first woman to become the governor of an Indian state, she was also the first Indian woman to become the president of the Indian National Congress. A firebrand independence activist and a feminist, Sarojini Naidu’s mother Varasundari, was a Bengali poetess too.

Naidu played a great role in awakening the women of India, urging them to come out of their kitchens and fight for their rights. Through her poetry collections Golden Threshold, The Bird of Time, The Broken Wings, The Magic Tree, The Wizard Mask and A Treasury of Poems, she reflected on the ideas of feminism and search for India’s soul in its common folk. In one of her poems, ‘Wandering Singers,’ she writes –

Here the voice of the wind calls our wandering feet,

Through echoing forest and echoing street,

With lutes in our hands ever-singing we roam,

All men are our kindred, the world is our home.

Our lays are of cities whose lustre is shed,

The laughter and beauty of women long dead;

The sword of old battles, the crown of old kings,

And happy and simple and sorrowful things.

What hope shall we gather, what dreams shall we sow?

Where the wind calls our wandering footsteps we go.

No love bids us tarry, no joy bids us wait:

The voice of the wind is the voice of our fate.

(Source : Poetry Archive)

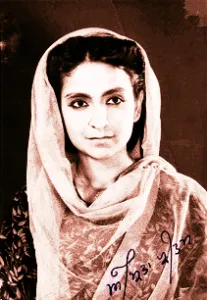

Amrita Pritam (1919–2005)

Known as one of the most important voices for modern Indian literature, Amrita Pritam was part of the Progressive Writers’ Movement and was vocal against oppression, crimes against women and rising intolerance in the society. One of her poetry collection, ‘Lok Peed’ (People’s Anguish), criticised the war-torn economy, after the Bengal famine of 1943. Her most famous Punjabi poem is ‘Ajj Aakhaan Waris Shah Nu’ (Today I invoke Waris Shah), an expression of her anguish over massacres during the partition of India. In the poem she writes –Today, I call Waris Shah, “Speak from your grave,”

And turn to the next page in your book of love,

Once, a daughter of Punjab cried and you wrote an entire saga,

Today, a million daughters cry out to you, Waris Shah,

Rise! O’ narrator of the grieving! Look at your Punjab,

Today, fields are lined with corpses, and blood fills the Chenab.

The poem was featured in a Pakistani Punjabi film, ‘Kartar Singh.’ Even after the partition when Amrita shifted from Lahore to India, she was equally loved by readers of both the countries. As a novelist, her most noted work was ‘Pinjar’ (The Skeleton), which was later made into an award-winning film too. The novel was a strong statement condemning violence against women, and loss of humanity due to fear and hatred. MS Sathyu, the renowned theatre artist and the director of ‘Garam Hava,’ also paid a theatrical tribute to Amrita through his play ‘Ek Thi Amrita.’

Irom Chanu Sharmila (1972)

The ‘Iron Lady of Manipur’ is known for her 15 years long ongoing hunger strike against AFSPA and military violence. As the activist poet continues the world’s longest hunger strike, she has also written exhaustively against insurgency and intra-tribal warfare in Manipur, including terrorism and government-sponsored violence between 2005 and 2015, during which more than 5,500 people died.Apart from being a political crusader, civil rights activist and a journalist, Irom is a brilliant poet too. Irom’s poems combine passion, protest and hope through vivid metaphors. It is interesting to know that despite her intense political activity, Irom prefers an innocent inconsequent existence. She is known for being publicity shy. In one of her poems ‘Like a child,’ she writes –

Without malice to anybody

Without hurting anyone

With tongues held right

Let me live

Like a child

A three-month old

Along with a long array of influences – political, personal, and social – women’s literature in India has evolved to show common experiences, a sense of solidarity towards women emancipation and a range of experiences that question the recurring problem of patriarchy and violence. As we ponder over these poets and their ideas, lest we forget that in an ever progressing history, it only the voices which questioned and didn’t surrender, that count.

Related Reads :

A tribute to modern Indian poets who were agents of social transformation

Calling closet poets, look what The (Great) Indian Poetry Collective is unveiling