Will the Union Budget bring an end to the e-commerce conundrum?

Vishal Krishna

Thursday February 25, 2016 , 6 min Read

Online retail constitutes just one percent of India’s total retail. Yet, out of the country’s nine startup Unicorns, three are major online commerce players: Flipkart (valued at $15.5 billion), Snapdeal ($6.5 billion), and ShopClues ($1.1 billion). Estimated to touch $38 billion in 2016, Indian e-commerce industry has grown impressively. However, hurdles for its potential growth are many – most of which related to government norms.

The tug-of-war between the physical retailers and online marketplaces mainly surrounds foreign direct investment (FDI). While the Centre in November 2015 permitted singe-brand retailers with FDI to sell online, the e-commerce sector can witness no major transformation unless FDI is allowed in multi-brand retail. It was immediately after that 21 e-commerce websites were listed by the Delhi High Court for investigation on violation of FDI laws. Although the order led to no serious investigation or shut-downs, and even had listed companies with no FDI, the lack of clarity regarding the sector continues.

While ‘Stand up, India Startup India' campaign brought relief to startups, the e-commerce sector is hoping for the same from the Union Budget 2016, to be announced on February 29. E-commerce Coalition recently expressed hope that the Budget will allow 100 percent FDI for online (multi-brand) retail, as it does in single-brand retail. At the Budget, the government may define the nature of an e-commerce marketplace business and possibly put an end to the confusion about what constitutes retailing.

What should e-commerce be?

In simple words, e-commerce is any commercial transaction done over the Internet. But in a simpler world, e-commerce would not need to be defined at all. According to Arvind of Technopak, the definition of commerce should be based on whether it is a physical channel or a distribution channel. “In the latter, it is just a channel for distribution of goods and services from a producer to a customer. To that extent, there should be no differentiation between e-commerce and physical retail,” he says. But as far as investments are concerned, every industry has investors from all over the world, Arvind says. “E-commerce is not an area to be bothered about. It is not national security, why worry about where the money comes from?”

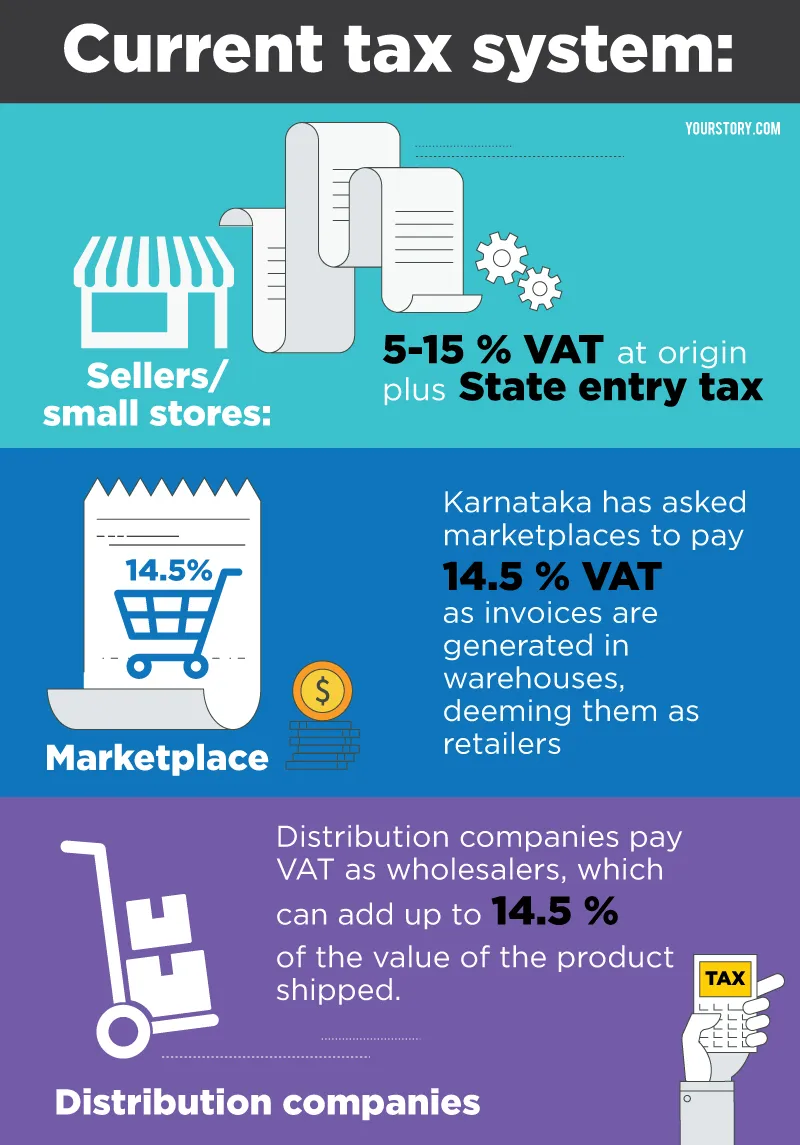

E-commerce currently falls in services category as marketplaces claim that they are just mediators so are not liable to pay VAT or CST (Central Sales Tax). Sellers end up paying not only VAT but service taxes as well, along with 2 percent to 50 to 55-percent commissions. In traditional business, commission was a fixed percentage. Even if it varies, there was no such drastic change. Also, the commission agent was charged taxes based on goods and not services.

What led to the confusion?

The hullabaloo over e-commerce is far from minimal. The Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion (DIPP) stated in January 2016 that it does not recognise marketplaces under FDI laws; within six weeks, it declared that it is considering allowing 100 percent FDI in marketplaces.

The ambiguity goes back to the law itself. The DIPP does not define what a marketplace is other than that FDI is allowed in wholesale retailing. It allowed all small merchants to sell on e-commerce websites like Flipkart, Snapdeal and Amazon. But these marketplaces had their preferred sellers like Prione, Cloudtail and WS Retail. These constitute 60 percent (according to sources) of the sales of the platform by value and so small retailers who use the marketplaces have taken their objections to the Delhi High Court saying that these marketplaces are direct sellers and not commission agents.

“By law, these marketplaces are not flouting any rules. They are at an arms-length with their distribution companies. But yes, there is confusion over the nature of transactions on a market place,” says Ganesh Prasad, partner at Khaitan and Company. However if the Central government chooses to ignore the definition then it is clear that the platforms' major sales come from its preferred distribution companies and it is not a platform for small retailers like it was intended to be in the first place.

The lack of definition has hurt the sellers in more than one way. The All India Online Vendors Association (AIOVA) hopes that by defining online marketplaces, e-commerce sellers can be recognised as a legal industry that can open up avenues to them. For instance, up until a few years ago, mutual funds were not recognised. Once it got defined, many regulations came up and helped reducing fraud and one-sided policies by fund managers. The AIOVA spokesperson told YourStory that e-commerce marketplace definition should specify that they should not indulge in buying or selling, or create entities like Cloudtail and WS Retail that they own, and must keep same policies for all stakeholders.

State & FDI: A complicated relationship

Karnataka was the first State to clamp down on marketplaces by sending them notices. The State, in its notice, said that marketplaces were generating invoices and were storing products in their warehouses and therefore needed to pay VAT. The marketplaces said that they could not pay tax because it was in violation of FDI rules if it collected and paid tax on behalf of sellers.

“The States are yet to understand the DIPP rules and the nature of a marketplace. In principle, there is no violation of the law, but since the Delhi High Court has asked for a probe into these marketplaces it allows States to send notices to the marketplaces,” says Prashant Kathore, partner and Head of Corporate Taxes, Ernst & Young.

The ideal future

Divisions more often than not bring about more confusion. Bringing all retail activity under one umbrella will make the business easier for all stakeholders, and policies can be made more consistent. Devangshu Dutta, Chief Executive at Third Eyesight, a consulting firm, says, “Today there are various artificial segregations, some driven by policy hangovers and some due to the evolution of the business itself. Having multiple brands versus having one single brand should be a decision that is driven by business strategy, rather than by government policy.”

There is a general consensus among experts that the government should not differentiate between categories of business in a sector that is growing increasingly integrated. Any change in rules in the retail sector should come from the ruling party. But in the last 15 years it has become a political issue more than an economic issue. Arvind of Technopak says, “Former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh brought the question of FDI in retail to the Parliament unnecessarily while it should have been a mere executive decision. It is now time to call a final shot in the issue. Finance Minister Arun Jaitley or PM Modi or Amit Shah as head of the ruling party should make a decision on whether FDI is needed or not; then DIPP can come up with a simple policy statement.”

While disruptions in business models are always welcome, whether or not the money is sourced internationally, it is essential to have clearly defined policies regarding the sector. E-commerce is the buzzword, but it has the potential to go light years. Defining the term is only the first step in that direction.

(Infographics by Gokul K and Aditya Ranade)