‘It requires breaking silence. It requires risking shame’ - Mapping Sexual Violence’s ambitious tech fix to address sexual violence in India

“Even though I write for children, and visit many schools, I had never spoke about my own experience. I started to meet a number of girls – in schools, as well as the daughters of my friends – who I began to notice exhibited the ‘classic’ symptoms of being sexually abused – depression, often suicidal, a habit of dressing and walking hunched over so as to hide the body, a loss of interest in school and physical activities,” says writer Samhita Arni. Having been a victim of abuse herself, she felt she could understand what it was, or, at the very least, recognise that the child was burdened by something that is hard to talk about. She did manage to get through to one girl and found out that she was, indeed, being abused sexually.

This experience pushed her to bring to the fore what she had been debating with herself for a long time. Samhita says, “I started to wonder that if I am a writer, perhaps I have some sort of obligation to start a conversation or discussion on these issues – isn’t that what writers are supposed to do? But I had no idea of how to. And that’s when I thought it might be interesting to get a bunch of writers to write about this, and see what happened – perhaps this would lead to others, who read this issue, to talk about their own experience. Perhaps, for those who had never been through this, they would finally understand and empathise with our reality.”

After this experience she felt determined to mobilise the collective experience of sexual abuse survivors in a way that help them deal with the shame and the trauma. “But,” she says, “I had no idea of how to do this, and couldn’t do it on my own. So I spoke to my friend Meena Kandasamy, who is a poet and writer, and has been through an abusive marriage and has written about it. And I also spoke to Indira Chandrakshekhar, who runs Out of Print and they were both hugely enthusiastic.”

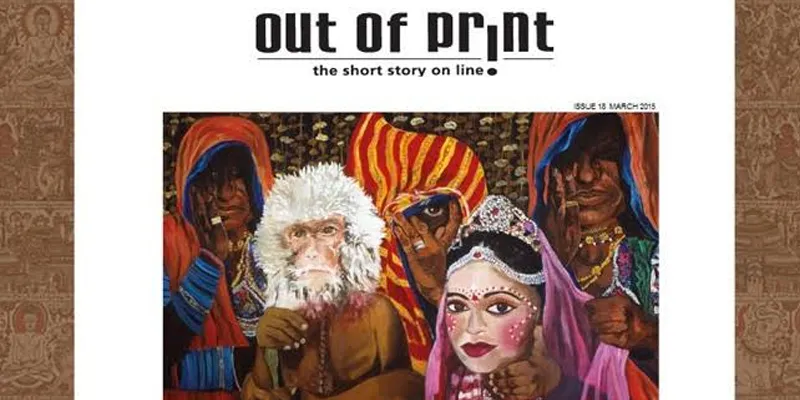

Out of Print is an online literary journal that Samhita edits. The three released a special issue of the magazine based on the theme of sexual violence. The issue was widely read and received immense critical acclaim in the media. But having started a mainstream conversation around this taboo topic, the women were loath to give up on it now that the issue was over and done with. Samhita says, “Meena raised the notion that the dialogue had to extend beyond writers – that everyone should feel able to write about their experience, so that’s how Mapping Sexual Violence was born.”

Why Mapping Sexual Violence

Mapping Sexual Violence is, as the name suggests, an app which maps stories of sexual abuse survivors from India and the south Asian region. The purpose is to, ‘Provide a platform to document silent voices, voices that have been unable to share their stories.’

Samhita knows first-hand how important it is to have a space to be able to tell your story without judgement and what the lack of such a space can do to a person. A survivor herself, she recalls that horrific period on her life, “It was my personal experience that did lead me to this project. I was eleven, and it was a one-time incident. But there was a deep sense of shame that prevented me talking about it to my family, and persisted years later. I was always afraid that I would Forever defined by this incident, by this sense of shame. I think many women experience similar anxieties. How does this affect our marriage prospects? These experiences can often leave us with psychological scars that can affect our marriages or relationships – how do we talk about this to prospective partners? Will talking about this in public shame our families? What will others think of us if we admit our experience?”

Samhita went on to become a New York Times bestselling writer and has received wide acclaim for her books from around the world. A supportive family and her becoming as a writer guided her to overcome that shame and sense of worthlessness that sexual abuse victims internalise. Now she is keen to give back. She says, “No change can happen, or will happen, unless we talk about it. I think it requires admitting – it requires breaking silence, it requires risking shame – to make others understand the desperate need for change. So it starts with an internal change – a desire, a need to break our own silence. And hopefully that leads to more and more talking openly about their experiences, and this can lead to something.

I have found it so liberating. Freeing. To speak about it was hugely liberating and empowering – taking control of my own narrative.

It has helped coming to terms with many things. The fact that I did not speak about it to my family led to many small resentments and tensions that accumulated over the years. To let that all go, to make with peace with that, has also helped me make peace with myself and my family.”

The safety of anonymity and the problems of sustainability

An ambitious idea, but Mapping Sexual Violence is most vulnerable to weaknesses inherent in its concept. It is the anonymity which grants survivors the autonomy to share their stories for public consumption. “We had to keep it anonymous. But at the same time, I do recognize that it is often easier to come out with your own story when you know someone else – and you can put a name and face to this person – who has.”

Upon its release in mid-2015, Mapping Sexual Violence was covered by every major news outlet in the country and was lauded as a worthy effort to combat this heinous, but silent, pandemic. Despite the positive start, the project’s growth has plateaued and its future looks uncertain. Partly the anonymity feature is to blame. Samhita says, “I have learnt that one needs continuous publicity to keep people posting. And since it is anonymous – there isn’t a word of mouth kind of movement – I shared my story, why don’t you share yours?”

Their plan to emerge out of the slump is to offer the platform to researchers who are working on collecting stories of sexual violence from rural India, to post their research and make it available online. “But this still hasn’t taken off,” Samhita rues. Out of Print’s issue on sexual and gender violence, which was the precursor to Mapping Sexual Violence, won the National Laadli Media Award for gender sensitivity at a glittering ceremony on 13th April. These highs among the slumps keep the project charging ahead.

A collaborative platform like this requires equal engagement from its audience. There is only so much its creators can push for when survivors themselves are hesitant to post. But, given the sensitivity of the topic, this was an eventuality the three women were prepared for. They are willing to give it the time it deserves. After all, for any change to be monumental, it has to be incremental. Gradually they hope, more stories will trickle in. “I feel like we’ve done what we can for the time being. But this is definitely influencing my writing, and the way I tell stories – I try to think of ways to use the digital realm to involve my readers, and make them come out with their own experiences and stories. I think there is a huge power in that – it is very healing and cathartic,” she says.

Everyone who worked on the project donated their time for free. Since there is no money involved, it has not come to a grinding halt despite the slow response rate. Mapping Sexual Violence continues to inch along and its creators have plans for when it does pick up: “If Mapping Sexual Violence serves a purpose, we hope to have this website available in other Indian languages and add features that connect resources to users and hope that this website can also become a networking resource.”

It is never your fault

Samhita’s parting note to fellow survivors is from the heart. “That what you wear can lead to sexual violence-and so the onus is on the victim- is absolutely, absolutely false. Whether women wear a burqa or miniskirt – they are still at risk.”