The parallel universe of Indian fintech

Of the sci-fi movies I’ve had a chance to catch recently, Coherence, a gripping thriller leads the list with a brilliant premise (if you are a sci-fi fan!). In it, a cosmic event opens the door to alternate realities on Earth – to parallel universes where things look the same on the surface but where events unfold in very different ways.

That’s also a pretty good way to describe the India fintech scene, in comparison to markets elsewhere in the world. At first glance, it may seem similar to what we see globally but it is actually quite different in terms of the opportunity, challenges, and the types of outcomes it is likely to yield.

The fintech opportunity drivers in developed markets are well known. They include millenials and their distaste for incumbent financial service providers; tech-savvy startups reimagining individual product lines (the well flogged unbundling concept); slow moving incumbent banks burdened by compliance, regulation and archaic legacy systems. US fintech startups alone have attracted over $20B in funding over the past five years (CB Insights data).

However, the opportunity in developed markets has a common backdrop – high financial services penetration. For example, the US has 70- 90% penetration across major categories such as auto insurance, lending, credit scoring, bank accounts, health insurance and more. For the most part, western fintech innovation is unlikely to dramatically increase total demand or create significantly larger markets. It’s hard to imagine overall consumer lending increasing by 20x in the US, a currently well-penetrated market with readily available credit.

The opportunity is very large – Goldman Sachs estimates $470B of profits at risk for traditional financial services firms due to fintech invaders. The nature of innovation is to make solutions better, faster and cheaper – using technology to vastly improve consumer experience and value. This is what one sees in the early success of a Kabbage, Prosper, Wealthfront, Betterment or Klarna – firms that effectively used data and analytics to provide a high-quality digital consumer experience. By becoming the platform of choice for a whole new generation of customers, fintech companies in developed markets can gain significant market share from incumbents, and over time reallocate profits in their favor.

How is India different?

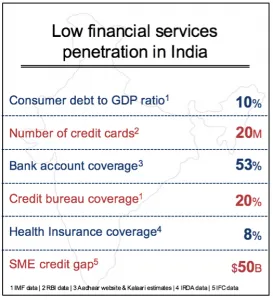

The single biggest difference in India is the lack of financial services penetration and the opportunity it represents. Yes, there are large Indian public sector and private banks with millions of customers but this pales in comparison with the hundreds of millions of people without any access to basic financial services. There is a massive opportunity to exponentially increase demand in almost every category – consumer lending, insurance, trade finance, digital payments, and investing, among others. In each of these areas, new fintech solutions can help grow the market significantly. So the opportunity lies in unlocking the door to a much larger market rather than merely reallocating market share amongst incumbents and startups.

It’s not that financial institutions in India have been blind to this. The promise has been around for a long time. The issue has been the economics of acquiring these clients, enabling efficient transactions, and building a profitable and scalable business. There are three main issues – the cost of the transaction, the risk of the transaction, and the cost of acquiring new customers. Balancing these variables while building a profitable business at scale has been challenging so far.

Most developed countries have a series of infrastructure layers that have been built over decades. These include electronic payment networks, credit scores, home ownership databases, bank accounts, government identity programs, and well-oiled credit card networks, among many others. Such plumbing allows electronic transactions to take place at acceptable levels of efficiency, security, and costs.

The absence of broad-based financial transaction infrastructure has been a major bottleneck in India and largely responsible for the lack of penetration. For example a loan in India requires loads of physical documents - identification proof, salary slips, notarised copies of all documents, wet signatures, in-person verification, physical inspections of property, and half a dozen other items that will fill up a fat binder. Similarly, without meaningful financial data the risk of lending to hundreds of millions of undocumented and unverifiable Indians has been too high even if many of them met the income sufficiency test.

But a ‘perfect storm” seems to have finally created an inflection point where technology, innovation, and favorable government policy is helping overcome barriers that have stood for decades in this area.

The India Stack – next generation transaction plumbing

The India Stack is an umbrella term used to describe a set of public APIs aimed at digitizing identity, customer verification, payments, and secure personal digital content. The India Stack initiative is spearheaded by iSpirit , a non-profit industry think tank in conjunction with various volunteer technology leaders, regulators and government agencies.

At the core of the India stack is Aadhar - the Nandan Nilekani envisioned national digital id program. Aadhar now covers a billion Indians and is a massive hi-tech biometric database that can now be pinged by any service provider. This is a huge step for India where, until recently, hundreds of millions of Indians had no formal government identification. The data collected by Aadhar forms the basis for electronic customer verification (eKYC), replacing the laborious physical verification previously required for financial transactions. While a few things are still being ironed out, most of the major Indian regulators such as RBI, SEBI (securities), IRDA (insurance) and TRAI (telecom) have broadly accepted Aadhar-based eKYC. In a single stroke, this cuts the time and cost of processing transactions by 50 – 80%, depending on the product or service. This alone is a massive step forward for India and fundamentally changes the economics of taking financial services to the masses.

In parallel, the government’s efforts to open bank accounts have seen greater traction. Over the past three years, 250M+ new bank accounts have been opened as part of the Jan Dhan Yojana program (JDY). By linking the Aadhar and JDY bank accounts for subsidy disbursement (over $60B in subsidies via this mechanism over the past 2 years) the government has managed to bring hundreds of millions of Indians into the banking system for the first time.

With the foundation for identification, verification and underlying bank accounts falling into place, policy makers have also taken aim at digital payments. The Unified Payments Interface (UPI) is an open API that banks can implement to allow phone-to-phone payment transfers directly from bank accounts. In theory, this will allow the 1B+ mobile phones and an estimated 500M smart phones (by 2020) to be used for everything from peer to peer transfers, kirana store payments, migrant worker remittances and other common financial use cases.

So, in a short span of time, India could potentially go from being a laggard to having cutting edge transaction infrastructure better than what’s available in developed countries. The interesting part is that this is being made available as free, neutral, open APIs that can be incorporated into any service.

As with any large-scale change, there may be several setbacks in implementing the India Stack. However, these are likely to be temporary technology integration hiccups, given the overall impact and broad-based change it can enable.

“Sachetisation” of Indian financial services

With some of the fundamental cost and data barriers of the past getting addressed, both incumbents and startups now have a genuine shot at innovating to take financial services to the masses. But there are still some major issues to tackle.

Even if transaction costs were to drop by 50% – 80% and digital connectivity makes them easier to market, it is highly doubtful that the current set of financial products and services will make much of a mark in terms of broader adoption and inclusion since the vast majority of these are designed for the top 40 million Indians.

The opportunity for fintech startups in India and incumbents is to use this moment to reimagine the needs of the rest of the population. There are about 400M Indians who make between Rs 2L ($3000) and Rs 10L ($15,000) a year. They have unique needs that have to be addressed with a new set of financial products. Unlocking this opportunity can triple or quadruple the total market for products such as small business loans, consumer financing, insurance, and capital markets participation.

Consumer packaged goods companies have long mastered the segmentation, packaging, distribution and pricing of products in a heterogeneous and low-income market such as India. For example, Unilever in India sells a 300 ml bottle of Sunsilk shampoo for around Rs 250 at department stores and also a 7.5 ml sachet for Rs 2 at the local kirana store. Almost 80%+ of all shampoo sales in India are of the sachet variety with good profit margins.

We see the India stack or even individual layers such as Aadhar, eKyc and UPI enabling the “sachetisation” of financial services in India. In our view there are two broad types of market opportunities that present themselves at this juncture.

The first is innovation around building segment specific vertical products unique to India and the needs of the next 400 million customers. We are seeing some early examples that include small ticket unsecured loans, pre-paid plans for single medical procedures, instant point of sale credit, pay per day insurance, micro-investment products among others. The key for these startups is to deeply understand the segment and create solutions that are usable, affordable and profitable at a micro offering level. The same applies for the SME market where there are a plethora of opportunities to satisfy strong demand for small business working capital, trade finance, and leasing.

It is uncharted territory yet. Many will fail but the ones with breakthrough innovation will go on to redefine the market space, bring about genuine financial inclusion, and reap the significant economic benefits.

The second play is around building horizontal platforms that assist incumbent financial services providers and the vertical fintech start-ups discussed earlier. For example, we see credit scoring using alternate data (transactional, social, geo-spatial, etc.) as being a horizontal utility over the India stack. Similarly, there is a big opportunity to become the consumer interface of choice to manage UPI based phone-to-phone payments. There are also white spaces in managing digital customer interaction via messaging platforms, or horizontal platforms that can manage the flow of verified and secure documents on top of the government-approved digital locker program.

Solving for demand aggregation and the last mile

We expect many large Indian fintech companies emerge over the next decade. But technology and product can only go so far in financial services if the business model is not designed for scale. In general, financial services is a profitable sector, but one built on aggregating demand and cross-selling multiple products at low unit transaction charges.

Fintech companies in India have the dual challenge of starting with much smaller ticket sizes and needing to scale to high volumes to build sustainable businesses. We see a lot of focus on technology and product but significant gaps in go-to-market strategy that can drive large volume.

Startups in China have done a great job of addressing this in different ways. There are those committed to an off-line to on-line approach (O2O) under which they use offline channels to aggregate demand that is fulfilled online. At the opposite end are large online platforms such as Alibaba and Tencent that have leveraged their hundreds of millions of e-commerce or messaging users to cross-sell a broad gamut of financial services from loans to investments.

Each Indian fintech start-up has to solve for this based on its product and customer segment. The ideal solution is an all-digital customer acquisition and fulfilment approach. However, in an evolving market with a lot of evangelising required, it’s often not the most effective for rapid scale. Leveraging other ecosystem players for access and mutual benefit is a legitimate strategy. For example, the business correspondent model used by banks is a relevant on-boarding channel for fintech solutions that require local access. Many regional NBFCs and cooperative banks have deep customer segment knowledge and are eager to partner for tech driven solutions. E-commerce platforms like Snapdeal, Flipkart and Amazon with large mobile customer bases seek to evolve into offering broader financial services. Large enterprises with suppliers and partners needing financing are also possible channels to leverage in the plan for scale.

India’s financial services sector is at an inflection point today. Indian fintech startups have a unique and in some cases larger opportunity than other global markets. But to win in this parallel universe, they have to find India-specific solutions that can place the next 400 million on the road to financial inclusion.

Thanks to Yash Jain (Analyst, Kalaari Capital) who helped with research and data for this article