This Diwali, how much money will delivery boys, the backbone of e-commerce sector, make?

Thirty-one-year-old Srinivas is running late. He is usually in Koramangala by 11 am. He has had to make a detour to his company’s office to sort out a few issues. By the time he reaches the 6th block in Koramangala that houses a row of eateries it is already 1.30 pm.

He logs on to his app anxiously. “Usually, most of the orders come in before 1 pm,” he tells me. Just then his smartphone sounds an alarm-like beep. His face lights up as he pushes the phone forward for me to see. “Ma'am, an order is coming in,” he says visibly excited. I find myself responding with the same enthusiasm. “Accept it fast,” I tell him.

A lunch order has been placed by a customer in HSR Layout to be delivered from one of the cafes near where we are parked. He goes to the café to place the order. As we wait for someone’s lunch order of BBQ chicken wings and a ‘Death by Bacon’ burger, I engage Srinivas with my questions trying to pack his 30-odd years into the 15 minutes that we have before he makes his way through the perpetual, agonising Koramangala traffic towards HSR.

Srinivas is one of the 60,000 (a conservative number) delivery boys in Bengaluru, who form the backbone of the burgeoning e-commerce industry. Assocham predicts that the e-commerce market in India is likely to touch $38 billion mark in 2016, a huge 67 percent jump over the $23 billion revenues for 2015.

These are not just cold statistics. Watch the numbers dance as the festival season approaches when you will see thousands of others like Srinivas negotiating the ever-increasing traffic of urban India to deliver ‘happiness.’

Flipkart and Snapdeal have reportedly hired 10,000 part-time delivery boys each across India to meet the huge demand anticipated from their respective Big Billion Days and Unbox Diwali sale starting next month.

Amazon, part of the big three e-com giants, has also fortified itself suitably to keep an increasingly consumption-driven society satiated with discounts and offers through its Great Indian Festival Sale.

Open season

Srinivas lives in Chickpet, a neighbourhood that still retains the old-world charm of Bangalore. He leaves home around 9 am daily to arrive in Koramangala at 11 am -- a journey of approximately 10 km made in two hours. This is the new Bengaluru, the startup neighbourhood of the startup city.

Srinivas has been working at Runnr for the past year as a delivery boy. He prefers to log in from Koramangala because this is where he can easily make 15 deliveries in a day, which helps him take home a little over Rs 20,000 a month. He has been able to get his sister married and is taking better care of his ailing mother who may have to undergo an operation soon.

Two years ago, Srinivas quit his studies to join the growing blue-collar workforce to support his family. “My first job was in a courier company. I was earning around Rs 10,000 a month, which wasn’t enough. One day, a friend recommended me to Runnr. I am glad I joined. In the first month, after working only for 15 days I got Rs 18000,” he says.

What attracts people like Srinivas to this job is the flexible working hours and the incentives. “Because of the approaching festival season we have seen more people come in for interviews,” says Falgun, who manages the onboarding facilities at Runnr.

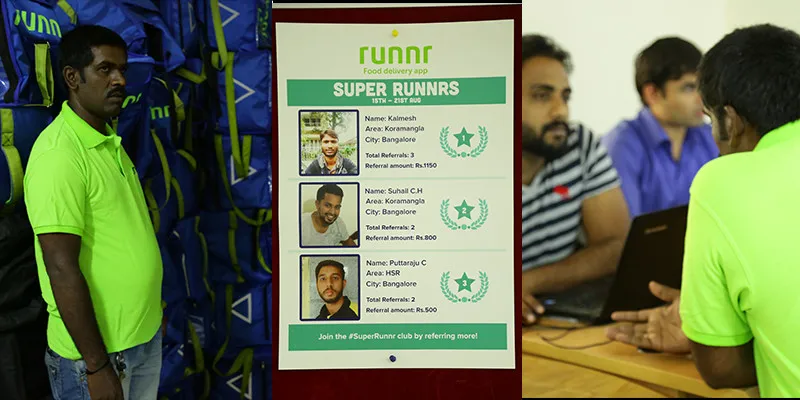

The startup has close to 1000 delivery boys in Bengaluru. According to him, during this season, a delivery person can make up to Rs 12,000 extra. The amount may seems like an exaggeration, but there is no denying that there’s more money to be made by everyone, including the delivery boys as Diwali approaches.

Weighing options

Delivery boys have an option of working either in the e-com or the foodtech delivery markets. There’s a big difference between the two, though. “My experience has been that people are more keen to take up foodtech delivery rather than e-com delivery. These deliveries are usually on-demand and are single orders. Plus, the delivery guys do not have to carry too much weight,” Dinesh Goel, CEO of Aasaanjobs, tells me over the phone from Mumbai.

Unlike foodtech delivery, e-com delivery is tougher. An e-com delivery boy makes 70 to 80 deliveries in a day. During peak hours or festival time, this number can go up to 120 deliveries a day.

That makes up for a lot of weight to carry. “There are advantages and disadvantages to both kinds of deliveries,” says Dinesh.

According to him, though foodtech delivery is less stressful than e-com delivery, attrition rates are high. Many times, because foodtech companies do not have proper processes in place, data reconciliation does not happen on time and the salaries of delivery boys get delayed. In e-com delivery, though companies like Amazon pays well and on time, there have been multiple cases of thefts and indemnifications. And because the value of the consignment is higher, in the case of accidents, the delivery boy risks more.

To overcome the high attrition rate among delivery boys, Big Basket is trying out a different strategy. In an interview with YourStory earlier, CEO of Big Basket Hari Menon, said, “Recruiting, training, and retaining delivery boys has been a little tricky for us. As the catchment dries up, we now go to smaller cities to hire them and provide them with affordable housing in the city of operations. This helps a lot in retention.”

Money matters

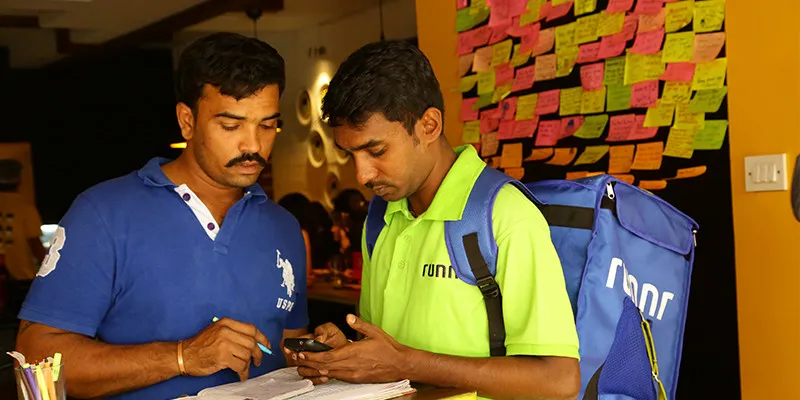

At the Runnr on-boarding office, I meet Shyam who has come for an interview. He used to work for Swiggy earlier and now wants to switch over. His onboarding process will take approximately an hour-and-a-half. The company will get his identity verified following which he will go through an interview where the interviewer will gauge his attitude, his appearance -- whether he is groomed well etc, and if he can speak basic English or Hindi besides Kannada. The process is more rejection based than a selection one.

The candidates have to have their own motorbikes and smartphones to download the company app. “We arrange for temporary bikes if a candidate does not have one, but they need to organise their own mobile phones,” says Falgun.

Interestingly, though startups maintain that they treat the riders as professionals -- they are called delivery executives -- and deduct tax at source, they do not provide insurance cover. Since most riders own their own bikes, the vehicle is insured by them.

As far as the payouts go, foodtech companies pay the delivery boys per delivery basis. “We have a minimum business guarantee. If they stay logged into our system for a certain number of hours, we ensure that they earn a minimum of Rs 500 a day,” adds Falgun. They are incentivised depending on the number of orders that they complete. Besides weekly and monthly incentives, delivery boys also make extra bucks by recommending a friend. At Runnr, they make Rs 2000 per referral.

According to a source, Amazon is the best paymaster of the lot. Besides paying on time and huge incentives, it also pays delivery boys for overtime if they exceed a nine-hour workday.

It is probably the only e-com company in India to do so. So an Amazon delivery ‘executive’ makes anywhere between Rs 15, 000 and Rs 18,000 a month that includes his fuel reimbursement, mobile reimbursement, attendance and peak hour bonus.

The faces of delivery

Manikannan, a Foodpanda delivery boy, is a pro in this field. He has probably tasted and tested most of the foodtech startups in Bengaluru, and if you care to listen he’ll tell you a thing or two about life as well. “So tell me, how much does a person working in a restaurant make?” he asks me when I catch him off guard relaxing with his pals from Swiggy in a peaceful bylane in Koramangala. As I do a shruggie, he answers his question with another one. “You know, at that Paradise hotel, a waiter makes Rs 7000. A courier guy probably makes Rs 10,000. Tell me how can one manage with that in a city like Bengaluru?”

Mani (“my short name,” he tells me) lives in Electronic City with his mother, and says he loves his job even though he works from 11 am to 11 pm. He claims he earns above Rs 20,000, a part of which he sends to his other family members living in Krishnagiri in Tamil Nadu. He hopes in three years he will have enough money to get married.

The lane where Mani and 10 others are chilling is their regular haunt. Every afternoon once they finish with the lunch rounds, they take a breather to exchange notes, check their WhatsApp messages or update their status on Facebook, before gearing up for the evening snack and dinner orders.

Abhi, the quieter of the lot, is new here. He is from Arekere near Bannerghatta Road and it has been three months since he joined Swiggy. He does not own a motorbike and instead rides his bicycle from his home to Koramangala daily where he chooses to fulfill the delivery orders. “The first month I earned only Rs 5000,” he tells me.

Abhi completed his diploma in Electronics and Communication from Mangaluru and had a BSNL exam scheduled for the day after I met him. He says if he gets through, he will quit the delivery job.

But Kiran alias Colourful Kiran is here for the long haul. “We have to learn to solve our problem,” he states referring to the loan repayment that he has to do after his family borrowed Rs 10 lakh for his sister’s wedding. Kiran is not in his ‘delivery fatigues’. He says he has taken a day off, but the chuckling behind his back indicates that he is fibbing. ‘Come on tell me why are they laughing?’ I coax him. His friends say that he has used up the cash he got from a customer through cash-on-delivery payment. “It happens sometimes,” points out the wise Mani.

Dinesh says that the Bengaluru market is a difficult one to crack. “At a recruitment drive we did for a foodtech company, the boys had come with letters from Amazon, Flipkart, and Swiggy. They told us, ‘we have offers from here already. Will you pay us more than this?’ The riders are well networked and seasoned,” he tells me.

Boxed for life?

Which made me wonder whether, like their Ola and Uber counterparts, delivery boys had also perfected a few hacks? “Even if they do, it does not amount to much because the volumes and value are not as high as in the case of Ola and Uber drivers,” says Dinesh, whose company Aasaanjobs provides blue-collar staffing solutions to many of its e-com, foodtech, and cab aggregator clients.

“Very often the delivery boys are at the receiving end,” adds Dinesh. Incidences of late payment of salaries, holding back incentives or fuel reimbursements abound. “They essentially do not have any specialised skills. What will happen when there’s a cut down in such jobs?” Dinesh asks a pertinent question.

We’ve already witnessed the first cycle of layoffs and shutdowns with PepperTap shutting down and Grofers laying off more than half its fleet. “Grofers paid its delivery boys well,” says Dinesh. What are they doing now? Having earned more money with less skill they will refuse to take up low-paying jobs. “The number of such jobs may go down drastically,” he says sounding a warning bell.

It is a scary scenario. But for now, the approaching festive season is the time when Srinivas and other road runners have an opportunity to make hay. Once the festival lights dim and fireworks fall silent, ‘itne mein bas thoda hi milega.’ For some in life, less is never more.

(Photos by R. Raja)