Buyer’s remorse post-Big Billion Days: How I learnt to stop worrying about discounts and love MRP

It was 11:59 pm on October 1, 2016, and I had three devices - a laptop, tablet and smartphone - spread out in front of me, signed-into three different e-commerce portals. (I could have opened three different tabs on my laptop, but where is the drama in that?) My fingers were ready and twitching to pounce on any interesting deals that would be revealed at the stroke of midnight, as part of the festive season sales that different e-commerce portals were running.

Image credit- Shutterstock

There were no real products on my ‘wishlist’, but the fear of missing out (FOMO) kept me glued to the multiple screens. By 12:02 am, I had scoured all three platforms and found reasonable deals, unlike the outrageous ‘Steal Deals’ that had gone out of stock within milliseconds back in 2014. I was about to call it a night when one particular deal that I had missed earlier flashed before my eyes and I immediately felt ‘buyer’s remorse’ - the sense of regret after making a purchase.

In front of me was a product I had purchased for Rs 4,000 more just two weeks ago, without giving too much thought. The product had been shipped and reached my doorstep within 24 hours and I was happy with the product and quick service. But in light of the new information, I started going through the different stages of buyer’s remorse.

Misery

As an Indian middle-class city dweller, the concept of making informed purchasing decisions and valuing money had been ingrained into me from a young age. So, a lot of miserable thoughts were running through my mind.

“Did I really need that product then or did I buy it to seek instant gratification?”

“Why couldn’t I have waited two weeks longer to buy it?”

“How many hours of overtime will I need to put in at work to overcome this ‘perceived loss’?”

With all these thoughts swirling in my head and no immediate answers, I decided to go to sleep and deal with the situation in the morning.

Acceptance

When I woke up the next day, I had far more clarity of thought and logical answers to my questions from the midnight mayhem.

The product I had purchased was a utility product I needed on a day-to-day basis, so it wouldn’t have made much sense to wait indefinitely for discounts, I reasoned. Also there was no foolproof way for me to estimate or predict when a product would receive a massive markdown. With a few mental calculations, I estimated the number of extra hours I might have to put in to ‘break even’ from this loss and realised it wasn’t as bad as I had expected.

Putting my personal troubles aside, this led me to ponder over a bigger question:

What if we lived in a world with no discounts but instead predictable markdowns on MRP?

While discounts currently drive sales for e-commerce players, it creates a lot of confusion in the minds of end consumers and also leads to buyer’s remorse, even after a good experience. In my case, though I had a ‘wow experience’ of getting the product within 24 hours in a neatly packaged and sealed box, the post-sales experience with the massive price drop two weeks later caused a lot of misery initially.

Also because of the way products are listed on e-commerce platforms, consumers need to rely on price comparison platforms to figure out what the real MRP of a product is and if the markdown and discount percentage listed are accurate. This consumes a lot of time and can be frustrating. In the days before e-commerce, most Indians would ‘window shop’ at multiple offline stores to check if the same product was available elsewhere at a better price. That same mentality and process has now moved online

Because of this ‘discount paralysis’ (similar to analysis paralysis), a lot of consumers postpone buying decisions hoping for the elusive better deal. While price comparison portals rely on algorithms to predict the best time to buy, we also need to consider the utility of the product and the pros and cons of buying it immediately.

Image credit- Buyhatke

End consumers would have peace of mind, if they could buy a product without having to monitor the rising and falling product prices, like companies listed on the stock market, then:

1. Consumers would no longer need to create a wishlist and play the ‘waiting game’ for the next e-commerce festival. There would be more predictability in demand and supply for retailers, instead sudden surges that occur during sales.

2. Consumers could start evaluating e-commerce portals on last-mile delivery experience instead of just price.

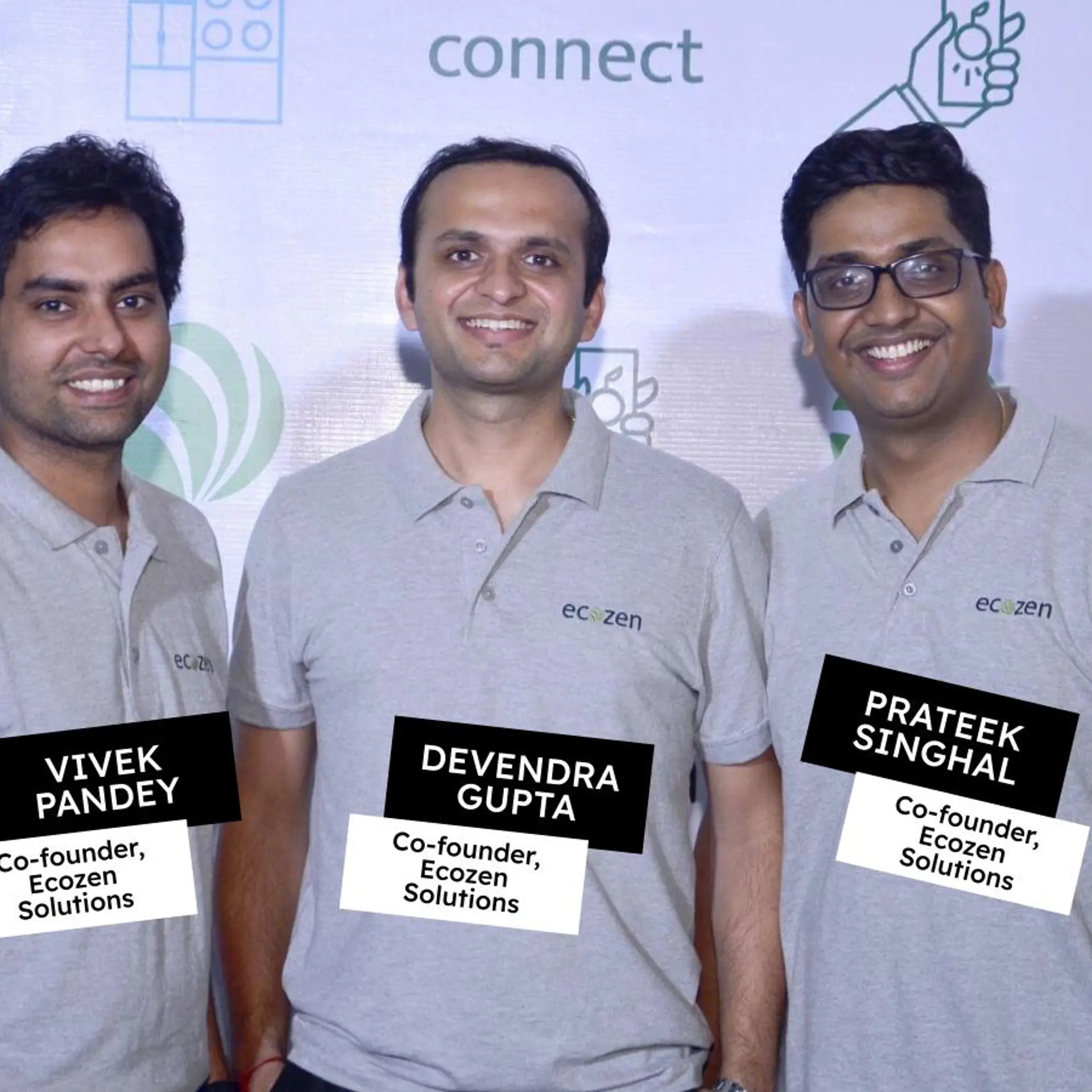

Some companies like Apple and Tesla have been open about their aversion to discounts. When Lyndon Rive, CEO of SolarCity, who is also Elon Musk's cousin, asked the Tesla Motors CEO for a family discount, Musk’s response was:

Yeah absolutely. Go to TeslaMotor.com (now tesla.com), buy the car online, and the price you see there is the family discount. Everyone gets a family discount.

More recently on September 29, 2016, a Reddit user mentioned that he had got a ‘discounted price’ on a Tesla vehicle. After being tagged on Twitter, Elon Musk was quick to respond and noted:

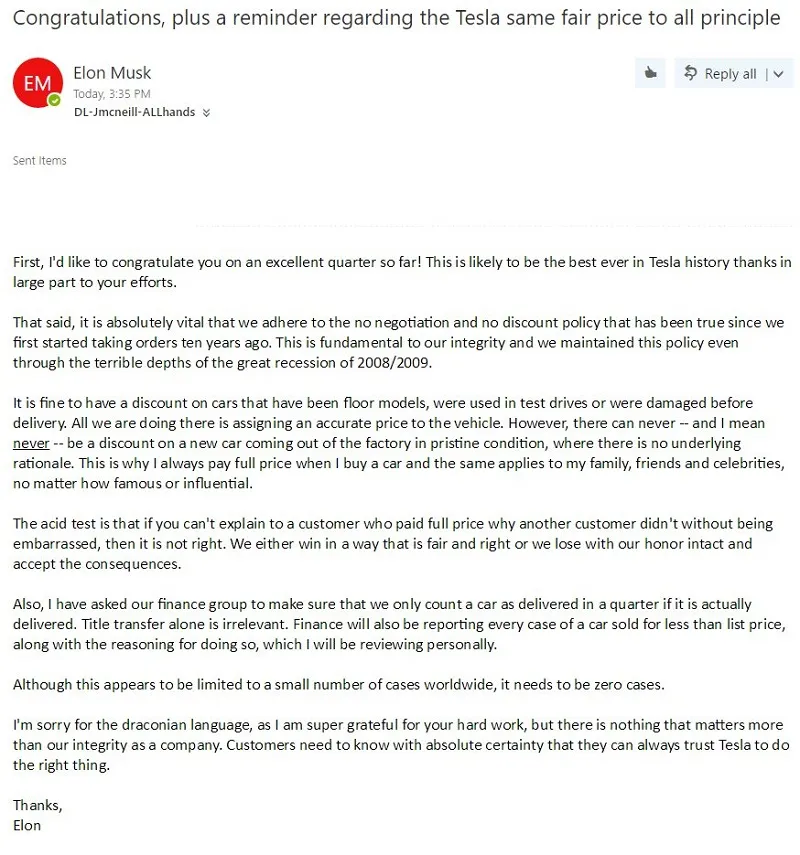

Musk also sent an email to his employees, going into detail about the importance of ethics and being fair to all customers.

The mighty Apple too has been known to stay away from discounts and was absent from Black Friday and Cyber Monday sales in the USA last year. But when it comes to consumer technology like smartphones, advances and innovation bring down the price of components quite quickly. So Apple and other companies are known to drop prices of older phones, when a new one is announced. The pace is not as rampant though in other industries, where prices can stay constant for a few years.

The e-commerce end-game

While e-commerce companies have great valuations, the margins are thin and running on the ‘discount model’ will not be a long-term sustainable strategy. Earlier this year, DIPP had instructed e-commerce marketplaces to stop offering discounts and put a cap on total sales originating from a group company or one vendor at 25 percent. But e-commerce players continue to run daily deals, other promotions and festive season’s sales to entice customers.

More recently in October, PTI reported that offline players, including traders body CAIT, have been raising concerns over advertisements by e-commerce players alleging that they infringe the guidelines. DIPP, though, clarified that advertisements for discounts by Amazon, Flipkart are part of the business and do not violate e-commerce guidelines.

According to DIPP guidelines, e-commerce marketplaces cannot offer discounts on their own and should not directly or indirectly influence the sale price of goods or services and should maintain level playing field. “There is no problem in giving advertisements. It is part of the business. They are also putting disclaimers that these discounts are extended by vendors,” sources in the DIPP told PTI.

E-commerce has gained sufficient maturity in India, at least in Tier 1 cities and already become a habit for many. But when the ‘smoke and mirrors’ around discounts settle down, will customers be too spoiled to purchase products at MRP?

Related read: How Flipkart, Snapdeal and Amazon redefined the festive season for consumers