[Budget 2017] What the Economic Survey tells us about India’s infamous demonetisation

The Economic Survey 2017 prepared by the Economic Divison of the Department of Economic Affairs was presented in Parliament today.

It is set against the backdrop of two major domestic policy developments in the past year — the passing of the constitutional amendment paving the way for the Goods and Services Tax (GST) as well as the move to demonetise Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes.

It mentions that although India’s move to demonetise the higher currency saw short-term costs, it will lead to benefits in the future.

Demonetisation has had short-term costs but holds the potential for long-term benefits. Follow-up actions to minimise the costs and maximise the benefits include: fast, demand-driven remonetisation; further tax reforms, including bringing land and real estate into the GST, reducing tax rates and stamp duties; and acting to allay anxieties about over-zealous tax administration.

The document also points out that the move was not unprecedented in India's own economic history — there have been two previous instances of demonetisation, in 1946 and 1978, the latter not having any significant effect on cash.

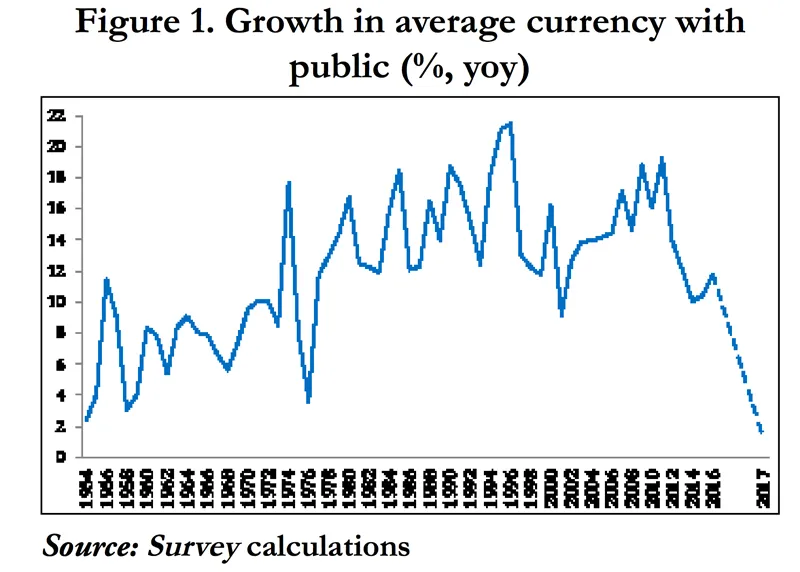

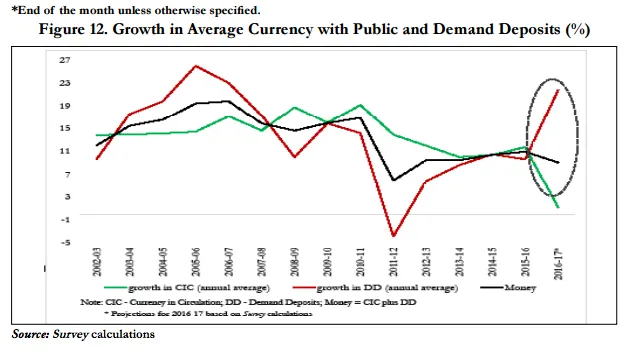

The following graph talks about the growth in average currency with public:

The report states that for 2016-17, change is expected to be only 1.2 percent year on year, almost 2 percentage points lower than four previous troughs, which averaged about 3.3 percent.

Why demonetisation?

The survey points out that although the main intentions were to curb corruption and the accumulation of black money, there might have been a few more reasons that pushed the government towards demonetisation.

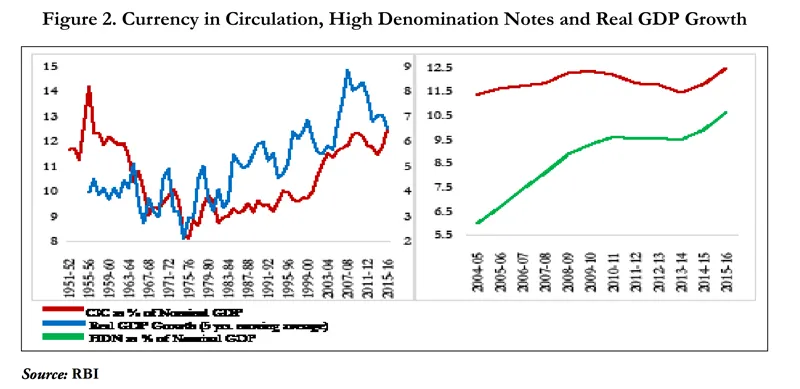

Following are a few observations from the report. To give a background, the survey states that the value of high denomination notes (Rs 500 and Rs 1,000) relative to GDP has also increased in line with rising living standards (stated in the right figure below)

The GDP debate

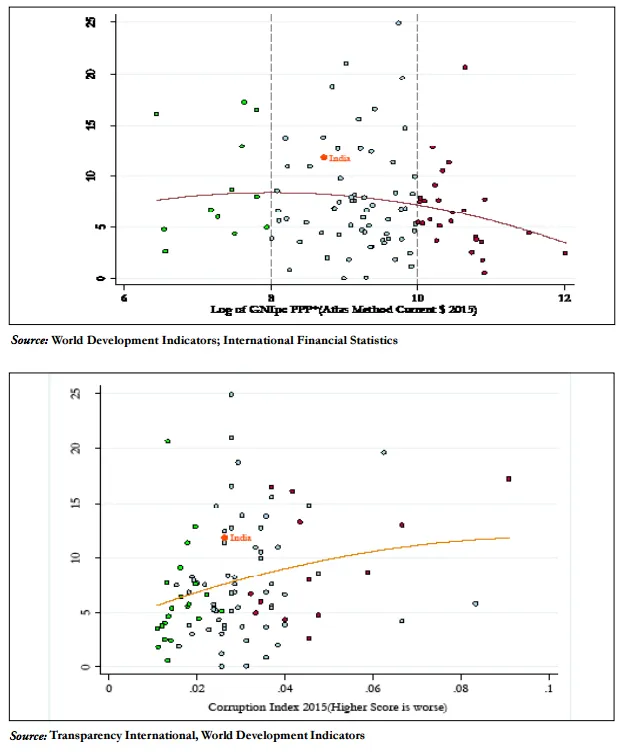

- In other developing countries, as the GDP rises, the use of cash declines, as demonstrated by the red line in the first figure below. However, in India’s case, the use of cash has risen (depicted by the yellow line, in the second figure) with the rise in GDP, stating that the survey presumes that the cash hoarded was used for corrupted practices and is black.

Further, the survey goes on to play the devil’s advocate, propagating two contrarian views,

‘Either, India’s level of corruption (or other related pathologies) is much worse than the index shows, so that the orange dot should really be placed to the right. Or cash is being used for other, presumably legitimate purposes.’

Soil rates

However, a good explanation of the degree to which Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 notes were used for transactions comes from 'soil rates'.

Soil rates are nothing but an indicator of notes which are considered too damaged to use and returned to the central bank.

The RBI rate states that in India, low denomination notes have a soil rate of 33 percent per year, while the rate for the Rs 500 note is 22 percent, and that for Rs 1,000 just 11 percent.

If all the currency is well enough in circulation (pre-demonetisation), all notes should soil at the same time. Moreover, in principle, the survey states that if a rupee-denomination note and a foreign denomination note fulfil a similar transaction function, then their soil rates should be similar (all else equal).

Yes, the survey does mention that high denomination notes might be used less owing to fewer high-value transactions in the country. But when the survey compared Indian soil rates (for denominations) using relative soil rates in the US (of their $20 and $50 notes), an estimated amount of about Rs 3 lakh crore comes up which is not used for transactions.

A figure representing close to 2 percent of the Indian GDP.

The analysis

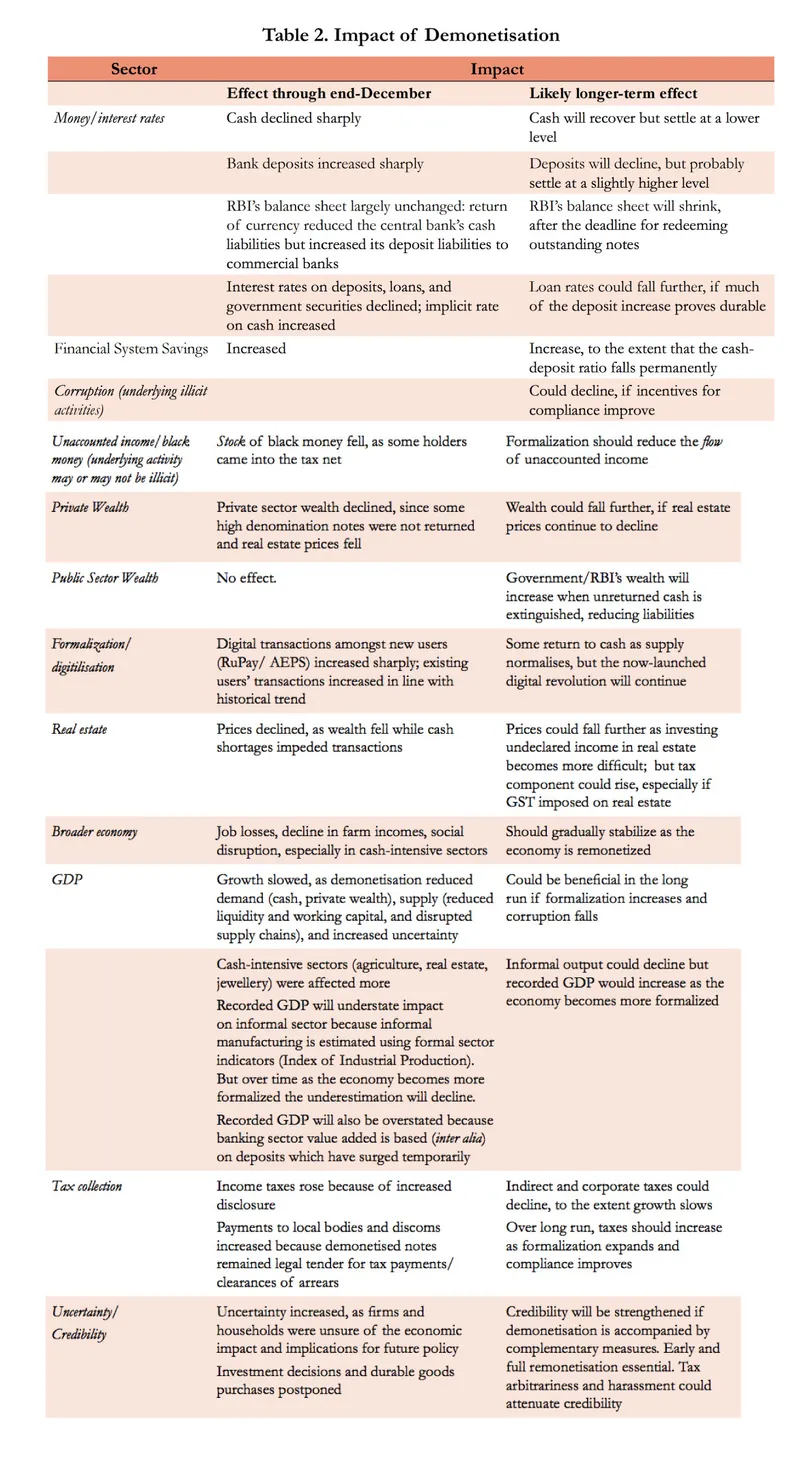

The following table captures and compares the impact through different financial segments from a smaller term to a larger impact:

1) Currency decline — less acute

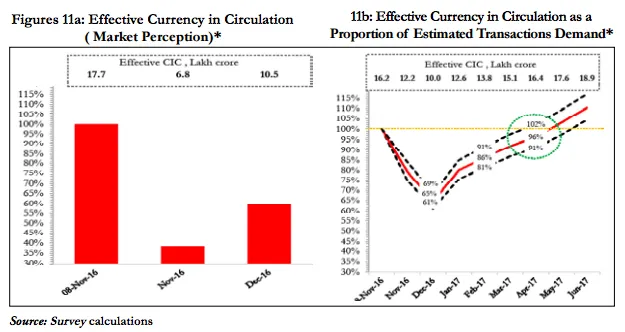

Indian Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian went on Twitter to highlight that the currency squeeze was less acute, but peaked later than perceived.

The headline numbers suggest that the currency decline after November 8, 2016, amounted to 62 percent by end-November 2016, narrowing to 41 percent by end-December 2016.

However, the survey says (stated in the graph below),

Our comparable numbers are 25 percent and 35 percent, respectively (in the figure below). In other words, the true extent of the cash reduction was much smaller than commonly perceived, and the true peak of the monetary — as opposed to the psychological — shock occurred in December, rather than November.

2) Tax on black money

The survey accepts that

Anecdotal evidence suggests there was, indeed, active laundering. One laundering mechanism seems to have been to 're-time' the accrual of income, by constructing receipts that made it seem as if the black money had just been earned in the period immediately before November.

But the survey settles in to say that black money holders still suffered a substantial loss, in taxes or 'conversion fees'.

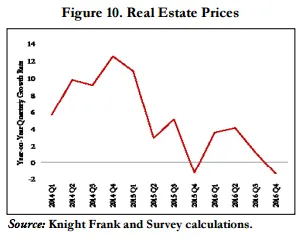

3) Real estate price drop

The following graph also shows a considerable drop in real estate prices, which was traditionally used to evade taxes. However, whether this will have a permanent impact is still to be seen.

4) Deposits increase as currency declines

Arvind Subramanian also tweeted stating that while there is a temporary fall of GDP growth by approximately 0.5 points relative to baseline, there will be a growth from FY18 onwards.

Why is there a fall in GDP?

Giving a reasoning, the survey mentions, the value of high denomination notes (Rs 500 and Rs 1,000) relative to GDP has also increased in line with rising living standards.

Second, India’s economy is relatively cash-dependent, even taking account of the fact that it is a relatively poor country.

Advice to remonetise

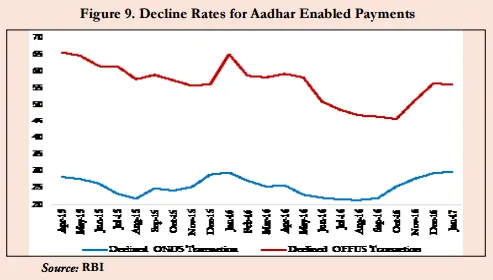

- Preventing banks from preventing interoperability

The survey, to quantify the degree of interoperability, compared the decline rate of transactions that involve the same issuing and remitting bank (On-US transactions) and on the one hand, transactions that involve different banks (Off-US transactions).

Based on detailed data provided by the NPCI, the decline rates were calculated for Aadhaar-enabled payments. Further, the decline rate stood at 56 percent for Off-US transactions, almost double of On-US transactions.

This hypothesis could be that larger banks were declining transactions involving smaller remitting banks, demonstrating a bias which needs addressing.

- Supply of currency should follow actual demand and not be dictated by official estimates of 'desirable demand'. Hence the RBI should re-establish the trust that public gets the amount they want, called internal convertibility. Further, the early elimination of withdrawal limits and removing penalties on cash withdrawal might mean less cash hoarding. The RBI just did so in the last few days.

- The government windfall arising from unreturned notes should be deployed towards capital-type expenditures rather than current ones. This means that government should spend on capital expenses, rather than current expenses like recalibration of ATMs and printing more currency.

- In the medium term, the impetus provided to digitalisation must continue, with public policy balancing both. Moreover, the transition to digitalisation should be gradual.

- Lastly, the survey states that

"Digitalisation must be incentivised — and the incentives favouring cash neutralised — the cost must be borne by the public sector (government/RBI) and not the consumer or financial intermediaries."

What was missed out?

But what is surprising that the survey doesn’t actively speak about cyber security, which will be a huge debate in the coming days. Throughout, it only says the following:

“That said, the security features of these e-payment systems will need to inspire trust, to ensure this trend continues.”

“To increase trust in digital payments, cyber security systems must be strengthened considerably.”

The survey mentions that demonetisation has led to an increase in digital payments, an aspect we haven’t explored in this story considering the amount of information already made available by the likes of the NPCI.

![[Budget 2017] What the Economic Survey tells us about India’s infamous demonetisation](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/wordpress/2017/01/Economic-Survey.jpg?mode=crop&crop=faces&ar=2:1?width=3840&q=75)