Plugging into renewables: the need for a long-term, renewables-based energy plan for India

Prices for renewables-based electricity have been dropping globally and more so here in India.

The Paris Agreement reached at the 21st Conference of Parties (COP) in December 2015 was a major milestone that capped more than two decades of global negotiations aimed at averting dangerous climate change. The outcome was reflective of wider acceptance that a low-carbon transformation of the world’s energy systems is indeed possible, even inevitable, in the context of rapidly falling renewables costs and an unprecedented degree of action by nations, civil society, businesses, industry, cities, and other stakeholders.

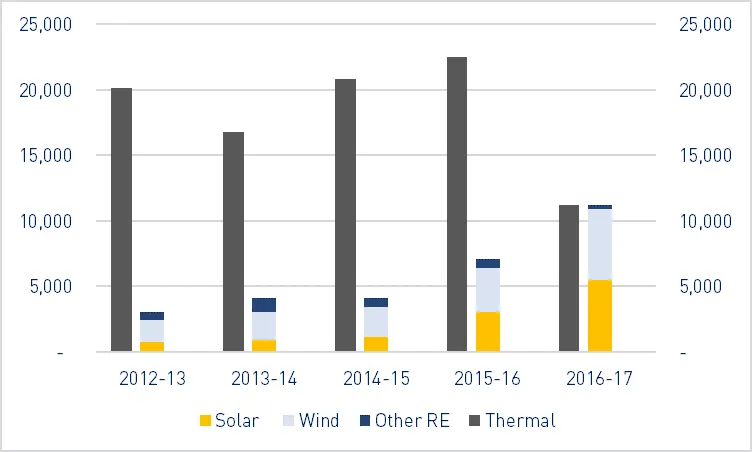

In this context, India has endorsed renewables as the future source to fuel the rapid growth engine. According to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), the country’s total renewable energy capacity including solar, wind, biomass, and small hydro grew by around 11,200 megawatts (MW) in FY 2016-17, which is at par with conventional thermal power capacity addition that registered a decline of 50 percent in comparison to the previous year. Across the country about 5,526 MW of new solar capacity (an increase of 83 percent over FY 2015-16) and roughly 5,400 MW of new wind capacity (up by 63 percent) was added in the year.

Despite the impressive performance of the renewables industry, the Indian energy sector continues to be plagued with multifaceted challenges. These include but are not limited to increasing energy demands with the rapidly developing economy and rising population, increased fossil fuel imports, deficits in meeting the electricity demand, and high shares of greenhouse gases from the energy sector in national emissions stack and still a lack of access to electricity to almost one-fourth of its population (26 percent of rural households). The government has recently revised the target of renewable energy capacities in India to 175 gigawatts (GW) by 2022. However, a long-term strategy to integrate large-scale expansion of renewables in order to address the above-mentioned multi-dimensional challenges is still missing.

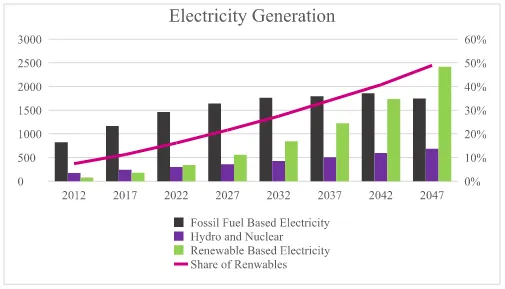

NITI Aayog, which was constituted by the Indian government to enhance the policy-making process, undertook an energy scenario building exercise—the ‘India Energy Security Scenarios (IESS), 2047’. This web-based planning tool presents two scenarios—the Maximum Energy Security Pathway (MESP) and the Maximum Clean and Renewable Energy Pathway (MCREP) in order to fulfil the energy demands in 2047. Considering the MCREP, the share of renewables in the enhanced proportion of electricity in the energy mix is estimated to be around 49 percent in 2047 in comparison to seven percent in 2012, whereas the share of coal is still around 37 percent of the primary energy supply in 2047 compared to around 46 percent in 2012, indicating a drop of just nine percent.

From 2010–2015, the indicative global average onshore wind generation costs for new plants fell by an estimated 30 percent on average, while costs for new utility-scale solar photovoltaics (PV) declined by two-thirds. Further, over the next five years, 2015-20, new onshore wind costs are expected to decline by a further 12 percent, while new utility-scale solar PV will decline by an additional 25 percent. Based on these developments, expecting a coal share of 37 percent in the Indian energy mix by 2047 seems unrealistic and quite out of date.

Prices for renewables-based electricity have been dropping globally and more so here in India, as observed recently—the winning bid at the Kadapa solar park being set up by NTPC is at Rs 3.15 /KWh which is the levelised tariff for 25 years with no escalation. This is lower than the lowest bid received for the 750 MW solar park in Rewa, Madhya Pradesh (which was around Rs 2.97/KWh and works out to around Rs 3.30/KWh over the lifetime of the power plant). Wind power too has been registering low costs in the range of Rs 3.50/KWh.

The effects of this trend of cost reduction in renewables is changing the dynamics of the power sector and rendering investments in conventional power plants unfeasible. Recently, The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis published a report which concluded that three new coal-fired power plants in the Netherlands are proving far less valuable than expected and are fundamentally out of step with power market trends across Europe. This is leading to debates on the economic feasibility of conventional power plants and calling for divestments of the fossil-fuel based power plants by some stakeholders. TERI recently published a report titled ‘Transitions in the Indian Energy Sector—Macro Level Analysis of Demand and Supply Side Options’ that suggests India should not consider building new power plants based on fossil fuels. There is a huge risk that these would turn into stranded assets in the near future.

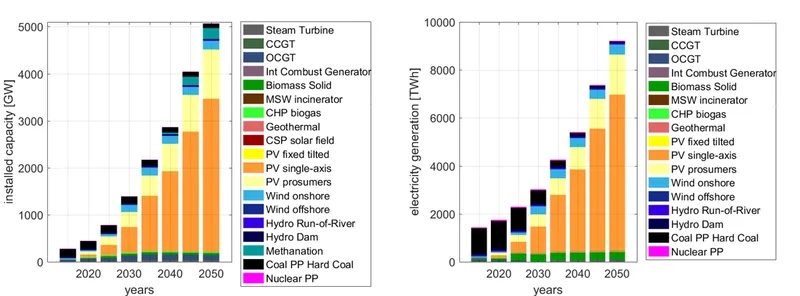

There have been reports on a 100 percent renewables-based energy system for India: ‘The Energy Report—India 100% Renewable Energy by 2050’ by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and TERI and the ‘Energy Revolution: A Sustainable Energy Outlook’ by Greenpeace. Recently, researchers from Lappeenranta University of Technology (LUT) have modelled energy scenarios globally as well as for India at an hourly resolution and derived the least-cost energy mix for 2050. Most of their publications in the context of India concluded that energy supply, fully based on renewable energy, storage, and distribution is the best and only option from the economic, ecological, and technical points of view. Already today, wind and solar power are the most cost-effective options for energy investments. In 2030, fossil fuel and nuclear energy will be non-competitive with renewables.

The results of the paper, ‘Electricity System based on 100% Renewable Energy for India and SAARC’ indicate scenarios where a 100 percent renewables-based energy system is possible and lower in cost than alternate high-risk options.

With the storage, load-balancing, and demand-balancing components, it looks like it is technically and economically feasible to build an energy system with a high amount of renewables. An important complementary solution to intermittent renewables will be storage and as a virtuous circle, development of battery technology which has been spurred by increasing viability of electric vehicles (EVs), which should bring further applications into the power market. The price of lithium-ion battery packs for electric vehicles have fallen 65 percent since 2010 and the trend is likely to continue making batteries cost-effective even for power storage.

The government is playing an active role in promoting the adoption of renewable energy resources by offering various incentives, such as generation-based incentives (GBIs), capital and interest subsidies, viability gap funding, concessional finance, and fiscal incentives but needs to develop an integrated long-term plan with renewables at the heart of it.

Some of the key aspects that such a plan could focus on are:

- Increasing the flexibility of power grids

- Developing the infrastructure for increased EV expansion

- Investing in storage facilities (a policy for storage technology development)

A future-oriented energy system in India will be based on solar PV, wind energy, battery storage, and flexible smart power grids.