How this 98-year-old rug company is transforming the socio-economic status of UP’s villages

OBEETEE, founded in 1920, is one of the largest hand-woven rug makers in the world but has stepped beyond profits by creating social impact through its various projects.

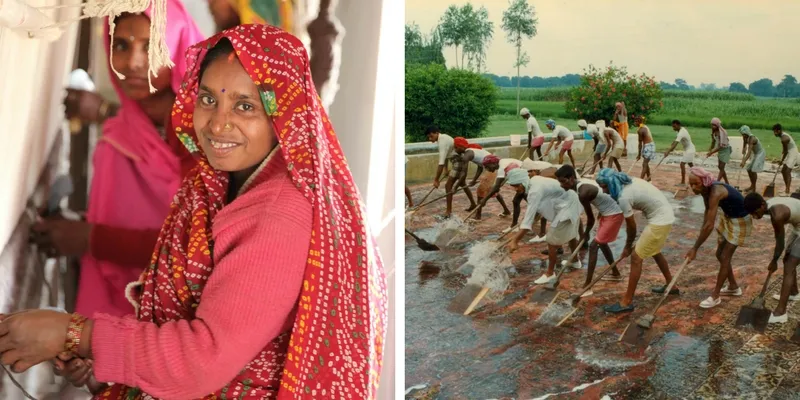

Being one of the largest rug makers in the world, OBEETEE provides employment to over 20,000 carpet weavers from villages in an around Uttar Pradesh’s Mirzapur district.

Gaurav Sharma, 46, OBEETEE’s managing director, joined the company in 1995. “I belong to Mirzapur as well and in 1978 or 1979, there was a flood in the area,” he says, recalling the time before he was even associated with OBEETEE. “I remember seeing the chairperson and MD sitting in boats carrying food and medical supplies for the weavers and other residents of the village.”

Taken by their efforts, he got on board. “I had just completed college at that time and thought I’d leave the company after gaining a year’s worth of work experience. I liked the work so much that I never left,” he says, capturing the spirit with which OBEETEE has been changing the lives of the women and children in UP’s villages.

Why Indian women need this opportunity

In countries like Turkey, Pakistan, and Iran, the weaving industry is women dominated—90 percent of the weavers are women. That is not the case in India, however. Most independent weavers find it hard to sustain themselves through this profession. Hence they may choose to migrate to cities like Delhi, Mumbai, or Jaipur for better opportunities. In the meantime, their wives are left behind at home, sometimes with children, devoid of an economic opportunity.

This situation is what inspired OBEETEE to do something about it. Hence, they thought of training programmes where women would be trained to become weavers over a span of three months. The carpet industry works on a piece rate system, and all the weavers are paid according to the area woven. To motivate them further, they are given a daily stipend of Rs 150.

In over 17 villages around UP’s Gopepur, training centres have been built where women are encouraged to learn weaving. The project began in late 2014 and since then has trained about 350 women.

OBEETEE works on an on-demand basis, producing what is already sold. In other words, the production of a carpet starts only when the client has confirmed the order. While this brings the question of consistency of work for the artisans, Gaurav assures, “There is some high and low, but we try to keep the business flow as consistent as possible so that we can support the artisans throughout the year.”

Post the training, the women are free to choose their employer. Around 55–60 percent of these women choose to work with OBEETEE. Others either don’t want to weave at all or are discouraged by their families. “Oftentimes it is their husbands, or the elderly women who tell them to not pursue weaving professionally and fulfil their domestic responsibilities instead,” Gaurav adds.

The training programmes are ongoing and before being launched in a village, the preparation can take up to five months. “The biggest challenge is to convince the women and their families that it is good for them. A great deal of talking, convincing, and cajoling is required before the women come on board. It is sometimes frustrating to see able women who need the money not joining because of societal rules and pressures,” Gaurav says. As a sign of encouragement, they have also added creches next to the training centres, where the nanny takes care of the children while the women learn weaving.

Gaurav believes that these efforts haven’t gone in vain. A group of students from Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) Poverty Action Lab has been studying the socio-economic impact of OBEETEE’s projects on the women of Gopepur, Mirzapur and the nearby villages for the past one year; the results have found a positive impact as evidenced by the increase in the number of women attending the training programmes.

Not forgetting the children

Considering that the ‘carpet belt’ in UP has been a hub for child labour, with thousands of children still working as bonded labourers, OBEETEE’s Project Mala has been a significant step to counter this situation. In fact, it was their first organised step towards creating a social impact. Started in 1989, the projects has so far been responsible for educating over 8,000 students.

In addition to the classes, the school also serves them breakfast and lunch, provides vaccinations, medical check-ups, and school supplies. Currently, there are over 460 students studying in the school.

“Since Project Mala started, we haven’t looked back and have tried to increase our activity to make as large an impact as we can,” Gaurav adds.

Other projects

OBEETEE has adopted Gopepur, where 90 percent of the residents don’t have toilets. Keeping the statistic in mind, OBEETEE decided to provide the families with their own toilets. Until now, 100 such toilets have been installed. They have also installed over 60 solar streetlights alongside the village roads.

Additionally, OBEETEE has geared up for a programme that will provide portable drinking water to over 1,000 families in the villages. They have also collaborated with the Ramakrishna Mission to set up a medical camp in Gopepur.

“Although we are trying to spread the impact on neighbouring villages, we want to focus especially on Gopepur and set it as an example of an ideal village,” Gaurav adds.

As a target for the current year, OBEETEE wishes to join hands with prominent NGOs across the country to increase the number of women getting training to over 1,000 a year and to increase the number of children getting education.