Two Indians who live zero waste lives share tips, tricks and challenges

Two environmentally conscious minimalists explain how becoming zero waste does not mean transforming into hippies, but adopting a lifestyle that your grandmother probably championed.

For the uninitiated, zero waste can be a daunting term. You may be conscientious about swapping plastic with cloth bags, regulating your water and electricity usage and being mindful about your carbon footprint. But then you come across zero wasters—people who produce no waste whatsoever—and feel insecure about the impact of your contributions.

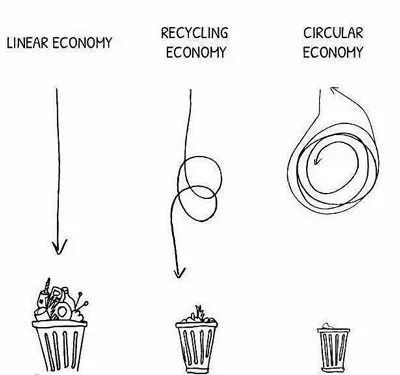

Zero waste is an abstract, not an absolute, term. We live in a linear economy where products are designed for the dustbin. Recycling is not a solution, merely a tool to delay the inevitable. Zero wasters advocate for a circular economy, where infrastructure, businesses and individuals see the value in the things they use. While the shift to a circular economy is a long way off, zero wasters live a life that comes closest to reflect the utopia that it can be. And they do this while living full lives, replete with family, friends and whatever entertainments modern life has to offer. It’s the how they do it where they differ with their non-zero wasting brethren.

Durgesh Nandhini: If cleanliness is godliness, I do my prayers every day.

Durgesh Nandhini is a homemaker with a three-year-old daughter and another baby on the way. Her whole family is proudly zero waste since 2015. Durgesh had been exploring alternative lifestyles long before she decided to go zero waste. She has been unschooling her daughter at home instead of enrolling her at a school because she believes children best learn through observation. She was experimenting with minimalism. Zero waste was merely an extension of the practices she had been delving into.

Durgesh’s journey into zero waste started when her then two year old daughter, during one of their unschooling jaunts, asked her about the 2bag1bin system of waste segregation introduced by Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), Bengaluru's civic body. To answer her numerous questions Durgesh dove into the world of household waste, plastic, recycling, composting, the gyres in the Pacific Ocean and much more. She says, “We together started to learn, explore, experiment and practice. I fell in love with Bea Johnson’s Book and Lauren Singer’s blog. Of late I am highly inspired by the many Indian zero wasters on Instagram. My daughter’s go-to resource is my grandmother, whom she questions a lot, about olden days waste practices.”

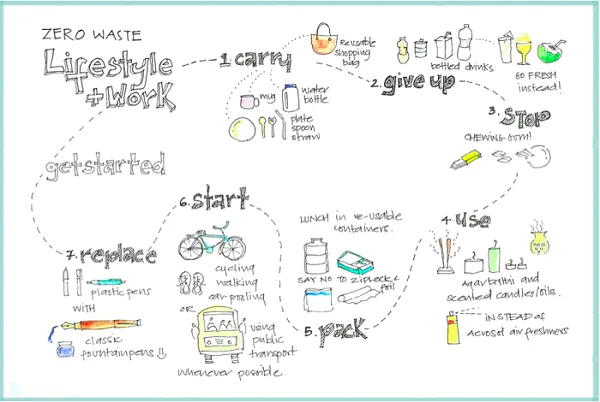

To start off with the zero waste life, Durgesh began at the bottom. She began segregating her waste. “My dustbin was my research centre. At the end of each day, I emptied my dustbin and took notes of each waste packaging material. I started to buy grocery in unbleached cotton drawstring bags, liquids in steel vessels. I replaced personal hygiene and cleaning products with homemade solutions created with kitchen staples. I carried my own container for takeaways when eating out. I came to know about minimalism and fell in love with it. Minimalism is the route to achieve zero waste,” she says.

Durgesh says she is not a hundred percent zero waster yet because the infrastructure in metro cities makes this lifestyle very hard. But she has come a long way since her days of studying her waste bin. “We generate about a half kg of collective non- recyclable waste every year,” she says. Compare that to the 62 million tonnes of garbage produced by the 377 million people living in urban India and we realise how miraculous a figure it is.

For Durgesh, though this started out as an experiment in environmentalism, she has stuck with it because of the health and financial benefits it has brought her family. “We have started to appreciate clean eating habits and our health have improved enormously. Our food expense has remained the same, even though we strictly don’t buy any packaged or processed food. Other than that our expenses have drastically reduced in every other arena of life. Before buying anything we question ourselves, ‘Once we are done with it, how will we dispose it?’

We have experienced true contentment since starting this life and it has brought us more happiness that material

wealth ever could,” she says. Durgesh says that the easiest thing about being zero waste in India is knowledge: “Zero waste practices were default in our culture a generation back. Though the initial inspiration came from zero waste westerners, I went back to the knowledge and practices of my grandmother to become fully zero waste.”

The hardest thing has been the waste disposal systems and attitudes she encounters regularly. Durgesh rues, “I segregate the waste at home and I personally take it to the physical recyclers and online agents. Though I am meticulous about it, the garbage collectors in my area still dump them all in one dry waste bin.”

People have decided opinions about the life Durgesh leads. She says, “I am often been mistaken as a person who worries a lot, takes immense pains to procure materials and staples for my lifestyle, a person who is always anxious about the future and doesn’t enjoy small pleasures of life. This is what people think, but what I do nourishes my soul. I have overcome all the challenges of being a zero waster through planning and organising.

A small act of mine has brought in a lot of learning for us as a family about environment, material science, radical consumption, slow fashion, agriculture, food safety and much more. And the amount of love and respect I have gained in blogging about my thoughts and practices is massive. Even if I’ve inspired one person to change one toxic habit in their household, then that is fulfilment enough for me.”

Sahar Mansoor: I needed to walk the talk

Sahar Mansoor first learnt of the concept of zero waste in 2012 while an undergraduate student at the Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. She remembers being dismissive of it. “We watched a video of Bea Johnson in class. I remember being blown away by her and her family’s lifestyle; but I also remember thinking to myself that she can afford to shop at Whole Foods or she must have a lot of free time to make her own products. I thought I couldn’t live a zero waste lifestyle while working three jobs, maintaining my grades for my scholarship, having a fun social life and exploring the new city I came to call home,” she says.

She revisited the idea in 2014 after coming across zero waste pioneer Lauren Singer’s blog. Then 24-year-old Lauren was living a waste-free life in New York. Sahar says, “I thought to myself if Lauren can do it, I can do it too, I am 24 too! I started to think more about our trash problem. The thing about trash is that we are so caught up in this web of convenience that we don’t think about our personal trash and often attribute to a larger global problem that we have no control over. Amy Korst rightly said, ‘Trash is intimately connected to every environmental problem we face today, from climate change and habitat destruction to water pollution and chemical exposure. It’s also intensely personal and impacts every decision in our daily lives, including everything from how much money we spend to how much weight we gain.’”

Sahar majored in Environmental Planning at Loyola Marymount and went on to do her master's in Environmental Economics and Law from Cambridge University. She currently works as an analyst at SELCO and runs a zero waste startup on the side named Bare Necessities. She believes that our trash problem is intricately linked to every environmental crisis looming over the world today. “We are subjects of this urbanisation-globalisation era and we are so caught up in this web of convenience that we don’t think about a plastic water bottle that we use for five minutes that then takes 700 years to start decomposing in the first place. Of course in the process leaching harmful chemicals into our soil and water, the same soil you are consuming your fresh veggies from!

When I first faced the facts, I couldn’t believe how something as innocuous as our garbage could be negatively connected to so many of my personal and political concerns. I wanted to stop being part of the problem. I had to address my own trash problem first. My solution – live a lifestyle that best reflects the values I cared about. I had called myself an environmentalist for about six years at the time but now I needed to walk the talk,” she says.

Though Sahar started off with Bea Johnson and Lauren Singer’s blogs, she too, like Durgesh, went back to her mother and grandmother for advice once she had transitioned to this lifestyle. “A lot of our Indian traditions are actually rooted in ecological practices or what we now can call ‘zero waste practices,’” she says.

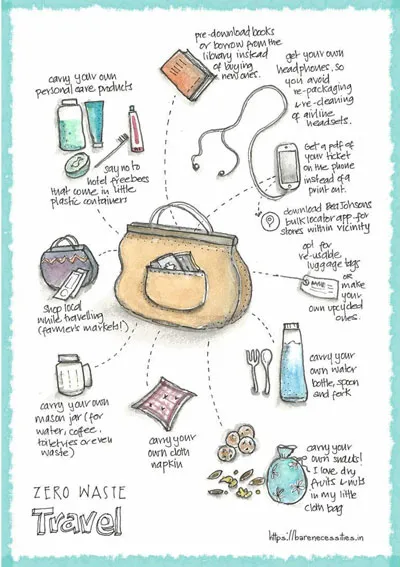

To start off, Sahar replaced single use plastic disposables with steel or bamboo ones (example, straw, toothbrush, and cutlery). Once she ran out of personal care products, she learnt to make her own soap, shampoo and other products. Now she manufactures these on a large scale through her startup Bare Necessities. She has produced 500 grams of waste in the past two years, which she stores in a glass jar. But she is quick to acknowledge her weaknesses. “I am still not completely zero waste – and I doubt I ever will be. It is good to know your boundaries. For instance, I wear contact lenses and that’s waste I produce every month but that’s my non-negotiable.”

Since going zero waste Sahar has experienced a three-pronged benefit in her life. “I am healthier since I no longer buy processed foods. I save money because I make my own personal and home care products. I am happier because I am prioritising just being and experiencing rather than acquiring and buying,” she says.

Living zero waste in the West is easier because India is not quite there in terms of legislation. Sahar says, “An advantage of living a zero waste lifestyle in the West I would say is that there is more awareness that has helped pass progressive legislation such as ‘extended producer responsibility laws’ in some countries in Europe and some US. states. Forward-thinking companies are finding ways to under ‘corporate responsibility’ or otherwise to take back, reuse, refurbish or recycle all kinds of things that otherwise would be thrown away. Thus, we are witnessing a mushrooming of eco-businesses and overall a movement to a ‘circular economy.’”

But living zero waste in India has its advantages. “India is the land of bazaars and small entrepreneurs. We love our homemade tinctures, DIYs, traditions - all things zero waste philosophy champions. Western zero-wasters probably don’t have access to their local tailor to make hand stitched clothes. I love buying local cotton fabric and having my tailor make me customised clothes. Way better than unethical, fast fashion and supporting local economy in the bargain,” she exclaims.

Sahar has no intention of preaching to people how they should live. But for those who care about the environment, she says this is the perfect place to get started. “It looks much harder than it actually is. If you care about your environmental impact - you should give it a shot. You can start by taking baby steps and slowly transitioning your life style. “It’s not time consuming, it’s not expensive and it’s not just for granola hippie people. Your grandmother was probably a zero waster.”