Attack on Babu Ram Chauhan will be treated as another criminal case notwithstanding that he helped remove encroachments on over 17,000 hectare of irrigated land

Babu Ram Chauhan always knew what was coming but he could not afford to drop what he was doing. Belonging to Ramgarh village located near India’s border with Pakistan in west Rajasthan, Chauhan exposed encroachment on more than 17,000 hectare of prime irrigated land in the area.

On July 11, he was kidnapped while returning home after teaching at a school 30km away from his village. The kidnappers beat him up badly, shaved his head and forced urine down his throat. They would have thrown him in the Indira Gandhi canal but for a few passersby who raised an alarm. Chauhan suffered fractures in both legs and one hand.

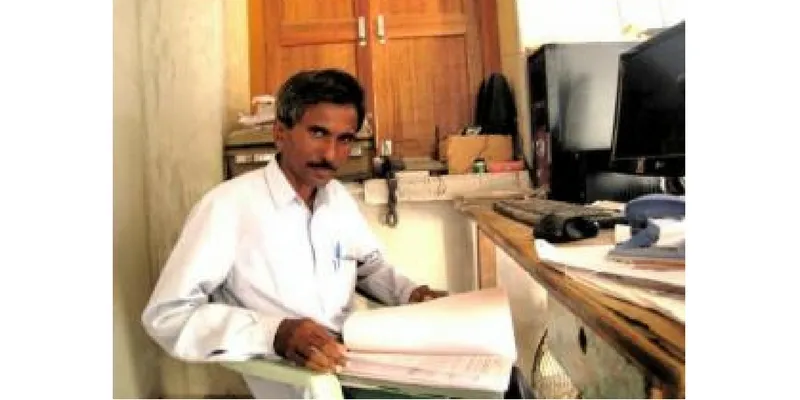

I had met him three years ago while doing research on victimisation of RTI users in Rajasthan and Gujarat for the Department of Personnel and Training (DoPT), the nodal agency for implementation of RTI Act.

A slim school teacher in his mid-30s, Chauhan came across as a strong-willed man ready to take on anybody. The recommendations I made in my report for RTI users drew heavily from his work.

What made Chauhan’s efforts unique was how he made an individual initiative into community work.

The work that matters

Ramgarh is one of the last settlements where the water from Indira Gandhi canal reaches. The land in its command area is meant to be allocated to landless farmers at subsidised rates. But land mafia, with help of local government officials, encroached upon the area depriving many deserving farmers of their titles.

Besides being financially strong, the encroachers were from the traditionally dominant Rajput community while the landless farmers mostly belonged to SC/ST communities. Chauhan, himself belonging to scheduled caste Meghwal community, knew that using RTI against encroachers would also disturb local power equations.

Since he was not to benefit from the allotment, Chauhan’s credibility as a self-less worker got strengthened. Around 200 co-villagers, who were awaiting land allotment, contributed money to support the efforts. Chauhan also trained them in filing of RTIs and scrutinising the government records. These trained people filed around 60 percent of all RTIs submitted to access land records. Chauhan also kept accounts of the donated money open for anybody to inspect.

When asked why he decided to expose land mafia, he had told me: “My father was able to support my education because he had a piece of land to cultivate. Imagine how many poor families will be able to improve their lot if land is allotted according to rules.”

Threatened by his work, the encroachers decided to get even.

An anonymous complaint was sent to the local administration in 2010 accusing Chauhan of being a Pakistani spy helping the neighbouring country procure maps of the canal area through the RTI Act.

Separate inquiries were initiated into the allegations by the CB-CID and the education department but the allegations were found to be baseless. During these inquiries, villagers came out in full support of Chauhan. The threats continued, directly from the land mafia and indirectly from local revenue officials but the work continued.

Over the last few years, most of the encroached land has been recovered and landless families given their entitlements. This further irritated the land mafia, which finally caught up with him on July 11.

That the attack included humiliating acts of shorning his head and forcing urine down his throat signifies that the assailants wanted to assert the caste supremacy as well.

Can we expect justice?

An FIR has been registered and four persons arrested and later released on bail. The Rajput community welcomed them home by taking out a celebratory procession through the village. Other seven accused,, including the main conspirator, are still out as the police claim to be investigating their involvement.

Before long, Chauhan will be another number in the tally of RTI users attacked or killed. A recent report by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative puts the number at 39 killed and 275 assaulted in last 10 years.

On June 20, a journalist-activist was killed in Gujarat for seeking questioning the police about illegal liquor trade. Just a day before, another RTI user from Madhya Pradesh was killed for exposing land mafia.

All these cases end up being treated like any other criminal case even though the victims do a great service by exposing corruption. Mangla Ram caught media attention in 2011 when he was attacked for seeking information about development works done in his village in Barmer district of Rajasthan. The victim accused the sarpanch and his supporters for the attack. Though a report was duly registered by the police, no arrest was made of the sarpanch, supposedly due to his considerable political and religious clout. Police claimed it was Mangla Ram who provoked the sarpanch’s supporters and the man himself was not involved. Those rounded up were also released on bail within four days.

A special investigation by a team of government officials into the development projects found glaring wrongdoings and unaccounted money amounting to Rs 361,750. In response, the state Principal Secretary passed orders to recover the unaccounted money and begin disciplinary proceedings against those found guilty, but no action has been taken against the accused.

Another case is that of Vishram Dodia, a street hawker who questioned the functioning of a power distribution company and gangs involved in illegal liquor trading and gambling in Surat, Gujarat. He was killed in full public view. A few persons were arrested but the witnesses retracted their statements helping the accused walk free. The Gujarat Police refused to provide investigation report I sought under RTI Act. Even after two orders of the Gujarat Information Commission in favour of information disclosure, the required documents are yet to be received.

There are many more such cases which die a slow death.

Where government fails, people succeed

Even after 10 years of the RTI Act, we don’t have concrete policy on protection of information seekers. A minor deterrent exists in the form of a decision of CIC that information sought by a harassed RTI applicant will be put into public domain. The state information commissions and respective government departments are yet to adopt the mechanism. The draft Whistleblowers’ Protection Act, which is also meant to cover common citizens, is still stuck with Union Law Ministry.

The only helpline for protection of RTI users is run by a Gujarat-based non-profit Mahiti Adhikar Gujarat Pahel which puts pressure on local administration to act swiftly whenever somebody reports threats or attack.

The DoPT restricts itself to issuing guidelines on proactive disclosures and refuses to stand behind RTI users. On learning about the attack on Chauhan, I called an official in the department asking if they could issue a letter to the district administration asking for a fair probe. “We don’t get involved in such matters. Many a times, these attacks turn out to be related to personal rivalry,” the official said. “True, but this is a person who is profiled in a research report commissioned and published by you. And seeking a fair probe is the safest statement one can make without favouring either party,” I argued without success.

Thankfully, Chauhan does not live on government support. Those living in hinterlands of this country can only count on people around them. Chauhan has no dearth of that support because of what he has done for his co-villagers. That it took land mafia over five years to actually carry out the threat signifies his support base. The road to justice is long and tedious but Chauhan does not need to wait for redemption. I am sure he will return stronger.

Disclaimer: This article, authored by Manu Moudgil, was first published on GOI Monitor.