Eye Mitra Opticians: French lens company Essilor is helping rural opticians set up business

Essilor has trained 3,150 people in India to become opticians. Known as Eye Mitra Opticians or EMOs, they are India’s fresh batch of entrepreneurs with a mission to cure uncorrected refractive error.

A road trip around Uttar Pradesh this September introduced me to 2.5 New Vision Generation (NVG) India, an initiative of Essilor Group that empowers India’s rural population through sustainable business models and brings vision screening and correction instruments to their doorsteps. An innovative part of 2.5 NVG is the Eye Mitra campaign, launched in 2013.

According to studies consulted by Boston Consultancy Group on behalf of Essilor, there are 55 crore people in India with uncorrected, poor vision. In simpler terms, so many people in our country require spectacles, but are either unaware of it or cannotafford vision correction.

Essilor’s Eye Mitra programme has brought quality, basic vision care to remote regions of India. The initiative has covered a total of 14 Indian states so far and enabled the screening of more than 25,00,000 people, of which a record 8,80,000 have now been equipped with spectacles, describes Gaurav Chauhan, Project Manager of 2.5 NVG in north and west India.

"The Eye Mitra programme helps identify zealous young people who have passed class 10 or 12to set up their own optical outlets in the community. A large number of youth are benefiting from the Eye Mitra programme and are presented with an opportunity to have a stable source of income with minimum qualifications. Migration from rural to urban areas is controlled, to some degree, by providing rural youth opportunity to work in their village," they add.

As of now, there are 3,150 Eye Mitras in states such as Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Telangana, and West Bengal. Gaurav says that there is never a dull moment in this programme.

We plan to have 1,300 new Eye Mitras in north and west India by the end of 2017. To enable people to do something with their lives is rewarding.

Caring for patients

Essilor’s Eye Mitras are spreading awareness about clear vision and providing villagers with spectacles at affordable rates. Most of the products they sell are Essilor’s own line of cheap eyegear. In the process, these local entrepreneurs are running their own shops.

Thirty-eight-year-old Iftekhar Ahmed of Sirsi village, 55 km from Rampur in Uttar Pradesh, taught Urdu and history in a private school, earning Rs 2,800 per month. After being trained as an Eye Mitra in 2014, Iftekhar earns Rs 22,000 a month. Like the other Eye Mitras, he, too, conducts vision screening events for free. “We can reach out to a large number of people through these events,” says Gaurav. “Without these, it would take us four to five days to achieve similar outreach.”

Iftekhar smiles and narrates how an old woman at an event in Jwalanagar came to him, holding her grandson’s hand.

She was unable to see clearly. When I tested her eyes and gave her spectacles, she blessed me. 'You have shown me the world,' she exclaimed, 'and my grandson’s face!' These blessings mean a lot, Iftekhar says.

Iftekhar had invested Rs 74,000 in his venture. Now, he tests vision for free for those who buy spectacles from him, and charges Rs 20 from others. “Patient satisfaction is crucial,” he believes. “One does not need advertisements if the patients are satisfied. Quality and service are equally important.”

A story of resilience

Twenty-year-old Saraswati Saxena of Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh suffered an accident in 2001 which broke the bones in her legs. After that, her bones grew weak and doctors told her she would never walk again.

I told them, ‘You put in 50 percent effort and I will put in the other 50 percent — together we will make it 100 percent worth of effort’. I wanted to show everyone that I would walk again. I called up the Eye Mitra training centre in Rampur, but they initially refused me admission because they thought it would be difficult for me as the classroom was up a flight of stairs. Besides, field visits required me to be physically active.

However, Sarswati persisted and not only completed the course with 100 percent attendance but also successfully set up shop in her locality. A biology student, she earns about Rs 8,000 a month, in addition to what she earns by giving private tuitions in biology. “People feel defeated by rejection,” she says, “but I think rejection means that there is some gap in mutual understanding.”

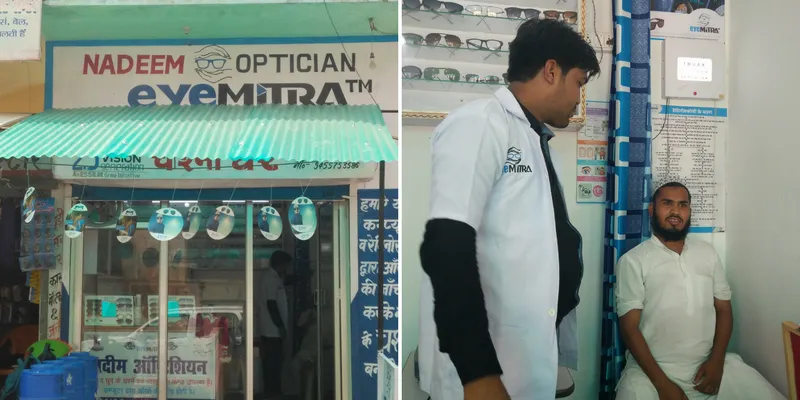

Nadim’s tale

At his shop in Sitapur, 25-year-old Nadim Ahmad Siddiqui efficiently checks for uncorrected refractive error. He has completed a bachelor’s degree in history and is studying for a master’s degree through a correspondence course. He gets customers from 65 localities around him and checks vision for free, charging only for spectacles.

He now earns Rs 40,000 a month, the highest in his family of seven. He now understands the importance of his role as a driver of public health in India, and has enrolled two of his brothers in optometry courses. For his younger brother, Nadim is setting up a computer centre in their village home.

Training and business support

Each training centre has a certain number of localities under it. Training consists of 30 percent theory and 70 percent practical work. During practical training, students are taught to use instruments. Later, they are taken to vision screening events where they hone their skills under experienced personnel. All of this is done over a period of two months.

We have a hand-holding system for our new Eye Mitras for the next 10 months. We give them business support, which includes guidance and the eye-testing kit. They are trained to be entrepreneurs, reports Gaurav.

Sajid Pashan, coordinator for five centres, says that no two days are the same in his job. There are three levels of selection for every candidate — the admission counsellor checks reports, financial status; the centre coordinator checks tactical, technical skills; and the admission counsellor ensures that the candidate is motivated enough to run a business. Admission counsellor of the Rampur centre, Sana Naim, knows within the first few minutes whether or not a candidate will qualify for enrolment. “We know who will stay and who will not,” she smiles.

Free training and business development support of 2.5 NVG is enabling thousands of people of rural India to run their private concerns. Along with this economic contribution, it is running its own campaign for better, clearer eyesight.

Enter the SocialStory Photography contest and show us how people are changing the world! Win prize money worth Rs 1 lakh and more. Click here for details!