As Kerala battles the worst flood since 1924, questions abound

Kerala comes to grips with the worst floods in recent history, but it’s time to take a look at what led to the calamity and what can be done to avoid it in the future.

When gates of the Cheruthoni dam, a part of the Idukki reservoir comprising Cheruthoni, Kulamavu and Idukki arch dam, were opened one by one on August 9, 2018, a torrent of water and mud gushed out. Heavy rains had led to the dam reaching close to its maximum capacity, forcing the authorities to open all gates.

Coming after a gap of 26 years, sufficient warning was provided before the gates were opened. The nearby town of Cheruthoni and the riverside villages were evacuated in time as the Periyar River swelled. The river gushed in full force, gorging on bridges, roads and houses downstream.

The people along the Pampa River, however, were caught unawares as the dams of the Sabarigiri hydro-electric project were opened hastily without a warning. The resultant fury of the floods left behind a trail of devastation in Pathanamthitta and Alappuzha districts.

Kerala has been battered by torrential rains since the end of May. A heavy spell since the evening of August 8, 2018, led to flooding in low-lying areas and landslides in hilly areas. In a short spell of 24 hours, the state received a huge amount of rain (310 mm). Two consecutive low-pressure systems that developed over the northern Bay of Bengal on August 7 and August 14 were responsible.

Over 400 people died in a fortnight and thousands were stranded. At least 12 lakh people were displaced and ended up in relief camps. The floods destroyed roughly 9.06 lakh hectares worth of crops. All the districts in the state were put on high alert till the waters receded. The losses to infrastructure due to the floods and landslides are pegged at over Rs 50,000 crore.

State failed to take notice of forecast warning

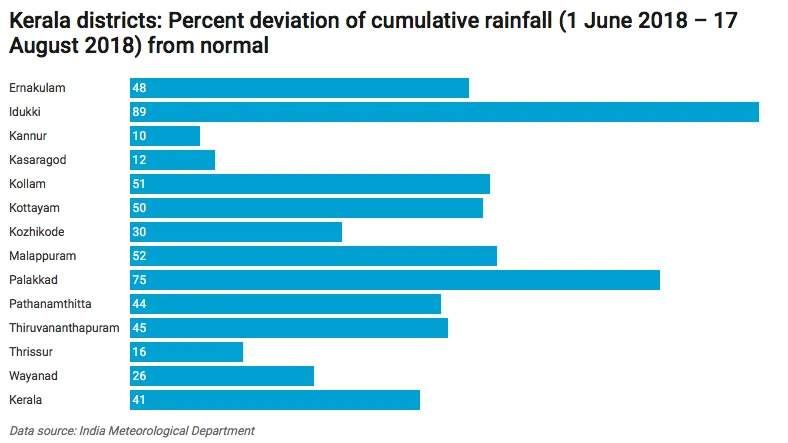

While Kerala as a whole has received 41 percent excess rain, districts such as Idukki and Palakkad received 89 and 75 percent excess rainfall during the period from June 1 to August 17, 2018. Water levels in the dams began rising since mid-July, as per data from the Kerala State Electricity Board; by August first week, they were brimming.

An article on the floods quotes Murali Thummarukudy, Chief of Disaster Risk Reduction in the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), as saying,

"Sitting in Geneva, I had on June 14 cautioned that the reservoirs will be filled by July. I had made the prediction based on the experience in Thailand and Pakistan. Unfortunately, our engineers did not foresee this.”

The India Meteorological Department (IMD) had predicted the likelihood of extremely heavy rainfall in August. This should have prompted the state’s dam authorities to slowly release water from the dams. But the desire to have more water to meet demands for electricity and irrigation overshadowed safety concerns.

In an article published in The Hindustan Times (August 21, 2018), Ashok Keshari, a professor of civil engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, said,

“The flood damages could have been reduced by 20-40 percent had the dams and reservoirs released the water slowly in the two-week period (in July) when the rains had subsided. The state did not have an advanced warning system in place and released water from the dams only once the danger levels (levels at which the dams structures can be damaged) were reached.”

Kerala is one of the 15 states and union territories of India where the Central Water Commission has not yet established any flood forecasting stations. The absence of forecast data on the level and the inflow of water made it difficult for the state to make informed decisions.

By August 15, 36 large dams in the state had to be opened as the water level had risen close to overflow level. This was a first in the state’s history.

Together, the waters wreaked havoc in low-lying areas.

This is what the dam boom and faulty dam management have come to in Kerala, a state that has been embroiled in a tussle with Tamil Nadu regarding the storage capacity of Mullaperiyar, a century-old dam, and its safety concerns.

Strong links to climate change

It is true that climate change renders rainfall patterns more unpredictable. As per research published in Vayu Mandal, a journal by the Indian Meteorological Society, an analysis of rainfall data from 1871 to 2011 for Kerala indicates a decline in the southwest monsoon but an increase in pre- and post-monsoon rainfall for the recent decades.

According to a study by Professor Timothy Osborn, Director of the climatic research unit at the University of East Anglia, United Kingdom “monsoons overall are expected to get wetter as the climate warms”.

In a recent report by the World Bank Group, average temperatures throughout India were seen rising and rainfall growing more erratic.

Man-made calamity, says Gadgil

Dr Madhav Gadgil, former professor of ecological sciences at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, has blamed human activity for worsening the flooding. He says exploitation of natural resources has left the area with poor natural defences to cope with heavy rainfall. In comments published by The Indian Express, Dr Madhav Gadgil who led a panel that published a report in 2011 on environmental protection in the Western Ghats, said,

“Had proper steps been taken, the scale of the tragedy would have been nowhere near what has resulted… Illegal stone quarrying had made flooding worse.”

Unfettered development activity in the Western Ghats had increased the chances of landslides, a major cause of casualties during the floods. The Gadgil report had found the highest number of vulnerable zones in Kerala among all the Western Ghat states. The report was sceptical about dams, and had warned against building them in the Western Ghats.

Wetlands, the water regime regulator, are under threat in the state. Kerala has also seen a loss in the area under wetlands or paddy lands, which acted as a sink during the rainy season—7.53 lakh hectares in 1961-62; 2.76 lakh hectares in 2005-06 and 1.61 lakh hectares in 2015-16, as per the National Wetland Atlas Kerala, MoEF&CC.

Wetlands have been lost to development projects, construction of roads, and buildings at places too close to rivers. The Kochi international airport, which was built after reclaiming a paddy field and lies within 2 km of the Periyar, had to be closed due to the floods.

Poor dam operation and safety

As climate change continues to show itself in full colour, floods like the one in Kerala will become much more frequent. Large dams, in particular, have become increasingly susceptible to catastrophic failure in the light of climate change-induced disasters. The recent Kerala flood has raised concerns over the issue of dam safety and the design of 4,900 large dams and several thousand small dams in India.

As per a CAG (Comptroller And Auditor General of India) audit of 2017 on dam safety in eight states, including Kerala, there was no integrated approach in identification of flood management works and Detailed Project Reports were not prepared in accordance with the guidelines.

Since 2010, Kerala has been involved in the Central Water Commission’s World Bank-funded Dam Rehabilitation and Improvement Project with the objectives of improving the safety and operational performance of selected existing dams through their rehabilitation. The programme aims to improve central and state-level institutional capacity to sustainably manage dam safety administration, operation, and maintenance.

As per the 2017 CAG report, Kerala had not conducted a dam-break analysis or prepared an Emergency Action Plan. Neither has the state prepared the Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Manuals for any of its dams. The audit also observed that prescribed quality checks were not conducted by monitoring agencies in all four projects in Kerala.

Latha Anantha, of the River Research Centre, Thrissur, in an interview with India Water Portal three years back had stated how the legal framework on dam safety “does not touch upon environmental impacts, both “upstream and downstream, in case of faulty performances, lack of proper sediment flush outs, sudden flooding of downstream due to uncontrolled releases of impounded water, dam failure etc.

In other words, the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF), which grants environmental and forest clearance to dam projects, does not have a role when it comes to dam safety related issues impinging upon the river ecology or livelihoods dependent upon rivers”.

What is the way forward?

Today what remains in Kerala are shattered livelihoods, properties, and the dreams of thousands of people across God’s Own Country. As we write this, army, air force and navy troops and the National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) are looking for survivors and undertaking rescue operations. They are aided by common citizens, from techies and film stars to college students and fishermen, who too have suffered the calamity but went beyond their means to offer help. Government and humanitarian organisations are organising medical help and providing aid in relief efforts. Kerala seems to be on top of the situation unlike Uttarakhand, which was clueless and indifferent while it faced the floods of 2013.

If only Kerala had taken up reservoir operation and management more seriously, the loss from the floods would’ve been mitigated. The Gadgil panel report calls for government intervention to curb activities such as quarrying, mining, land clearance or construction in ecologically-sensitive zones such as those close to riverbanks and violation of Wetlands Protection Rules too need to be looked into.

The Kerala government (Chief Minister’s Disaster Relief Fund) has started a donation website for flood victims.

Disclaimer: This article was first published in India Water Portal. The views expressed by the author are his/her own and do not necessarily reflect that of YourStory.