India 2019 general elections: The critical overs of the power play begin

More than 800 million Indians will vote in the 2019 general elections. What India decides to do then is important not just for the country, but for the world. If one-sixth of humanity decides to vote for inclusive growth within a democratic set-up, the coming two decades will see global poverty decline and new markets open up for economies across the world.

In April or May next year, more than 800 million Indians will vote to elect the representatives to the 17th Lok Sabha (Lower House). So, what is at stake? The future.

The fact is these elections are not just “make or break” in the hyperbolic, headline-grabbing sense. I believe they are so critical that when historians in the later part of this century look at India, they will look to the polls in 2019 and 2024, either approvingly or with regret.

In Shanghai, when you ask a Chinese investor or business executive why they are so bullish on India, the most common response that underlies their conviction is its rapidly growing young population.

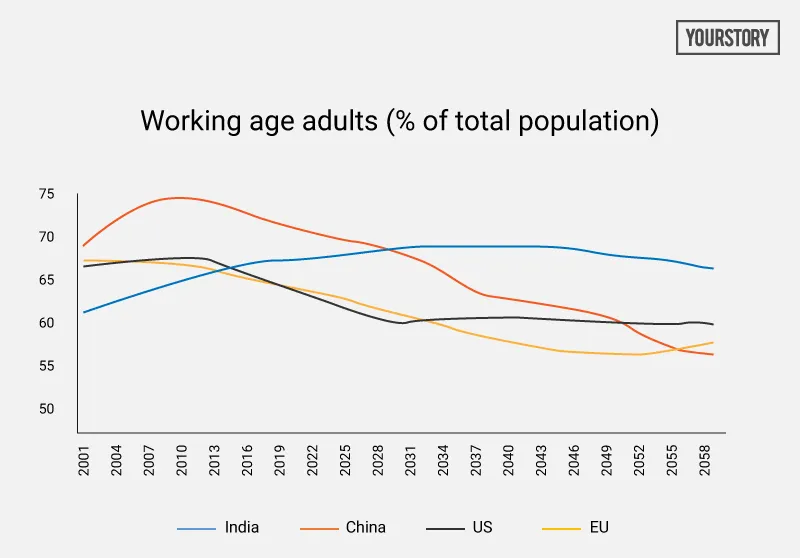

They cheerfully compare how infrastructure wise, India is where China was in the late 1990s or early 2000s -- at the cusp of a dramatic improvement in the living standards of the people and a significant upgrade in their purchasing habits. They rightly point out, that since India did not impose the one-child policy like China, the length of the demographic dividend will be much longer in India’s case (51 years), as compared to China’s case (17-18 years) (See chart below).

Figure 1: India is likely to enjoy a longer period of demographic dividend than China, with more than 2/3rd of its population remaining in the working age until 2050.

However, this underlying prediction assumes that India will be able to accomplish what China had successfully managed between the late 1980s until 2010 – finding gainful employment for the tens of millions of people who entered its labour force, which sparked a boom in housing, autos and consumer credit.

In India’s context, it is interesting to quantify how enormous those challenges are, notwithstanding the longer tailwinds of favourable demography it will enjoy, relative to China. Demography is not destiny, especially for countries with large populations.

As an interesting report by Morgan Stanley pointed out, over the past thirty years of globalisation (1987-2017), of the 74 countries that were classified as middle income or developing, only 19 made the transition to high-income or developed category. Of this, only two countries, South Korea and Poland, had populations of more than 20 million. Even China, for all its breakneck growth and improvement in living standards, remains a decade or two away from graduating into the ranks of developed countries. Surely, being young is not an automatic guarantee to being prosperous.

Graduating to a developed nation

India has a Gross National Income (GNI) per head of $1,820, and a GNI growth rate averaging 5.6 percent over the last decade. This is roughly how an average Indian’s income stands as of 2017 and its growth rate. Considering the average working population growth rate of 1.6 percent per annum since 2000, this translates into a GDP growth rate of about 7.2 percent for the economy.

Should the country continue to grow at this pace, India should reach the income and living standard levels of Thailand and South Africa in a generation, and Czech Republic and Greece in the next generation, both of which incidentally lie in the lower half of the list of developed countries.

Becoming the next China in one generation and graduating to the ranks of Western European nations in two, will require India’s GDP to grow at double digits, consistently for the next forty years, a feat that no country in the history of humanity has yet been able to manage.

To bring back the cricketing analogy, demographic dividend is a sort of power play -- a younger population makes it easier for you to hit higher growth targets. But the problem is that the total that India is chasing is so daunting, that it requires close to 10 runs an over to close the chase.

Implicit in the market’s assumptions of a strong growth rate for India is that it will naturally lead to a healthy rate of employment growth, after all, more output means more firms will want to hire more people.

While India has not been pushed into a state of “jobless growth” as the critics of 1991 economic reforms like to claim, the rate of growth in employment has still not matched that of economic growth.

To illustrate, the average elasticity of employment to growth – the growth in employment per 1 percent increase in GDP growth -- for the countries (mentioned earlier in this article) who graduated to being developed from developing was 0.5.

This meant that for every 1 percent increase in growth rate in these countries, employment growth increased by 0.5 percent. That number had been much smaller in India even in the first decade of economic reforms (0.4), and has fallen sharply in the last decade to just 0.25.

The primary reason behind this anomaly, at least in our view, is the strict labour laws, relative to other developing economies and the relatively high social security payments that fixed-term contract employers have to make in favour of workers.

These disincentives induce employers to either invest heavily in capital and automation, or opt for contract labour, where investments in skills and employability are decidedly lower than that for full-time workers.

Balancing growth and employment imperatives

At the present growth rate of population, India should see on an average 10 million people join the workforce each year, for the coming decade. Given that the current employment is 473 million, as per the last census data, this requires a 2.1 percent increase in employment opportunities for youth every year.

If we assume that the elasticity of jobs to growth remains the same, i.e. there is not a significant change in labour laws either at the state or the central levels, India will need to consistently hit the 10 percent GDP growth target just to keep every jobseeker gainfully employed.

The experience of other Asian success stories in countries like Korea, Taiwan, China, and Singapore shows that a sure-shot way to balance both growth and employment imperatives is to wean people off agriculture in more productive occupations such as manufacturing, construction and services.

However, so far, the record of all governments in creating non-farm jobs in India has been abysmal. Census data from 2011 shows that just six regions in the country – comprising less than 30 districts out of 640 in the country - have more than half of their population working in non-farm occupations.

Furthermore, despite the fact that increasing employment is such a big challenge for any incumbent future Indian government, it is a shame that neither India’s statistics office nor the RBI have any high frequency indicators of employment data, which can serve as a real-time health check on the labour market in the country. Especially given that almost all the large emerging markets (except China) have such statistics.

The lack of credible data itself opens the door to all sorts of anecdotal claims and biased measurements. Indeed, an estimate of jobs created in India over the last year ranges between 1.5 to 12 million, depending on who you ask.

Job creation a key priority in the 2019 elections

The reason why job creation is the lens through which the future will look at the general elections in 2019 is that all the other visible social conflicts today are the manifestations of this problem. Rising population, climate change and fragmentation of land parcels have made agriculture a risky enterprise for the small farmer.

However, gainful employment opportunities are available to the landed peasants only as unappealing, contract-based non-farm labour jobs. This has led to agitations for caste-based reservations in government jobs, protests for waiving off loans and the accompanying response of the state governments to run large fiscal deficits by providing freebies and kicking the can down the road.

Long-term underemployment also impacts psychology, undermining the people’s faith in social institutions and pushing them towards more radical solutions and crime.

The reason why fundamentalists on both sides of the divide are so easily finding recruits on the streets and the social media is because the youth on the wrong side of the labour market have much less at stake with the status quo and want some, or perhaps any, source of agency to change things.

What India decides to do in May is important not just for the country, but for the world.

If one sixth of humanity decides to vote for inclusive growth within a democratic set-up, the coming two decades will see global poverty decline and new markets open up for economies across the world, much as China emerged from being the world’s biggest factory in the 1990s to the world’s preferred market in the current decade.

Indian youth of today, who comprise more than half of the electorate, have a choice at hand -- 40 years from now, what kind of country they would like to breathe their last in.