[Techie Tuesday] How Prashanth Susarla helped PayU grow 5x after almost flunking out of IIT-Kanpur

In this week’s Techie Tuesday, we tell you about Prashanth Susarla and his journey, including stints at OATSystems Software, Andale, and Microsoft. Now Cofounder and CTO of Unilodgers, he grew PayU from a Rs 12,500 crore business to a Rs 60,000 crore business.

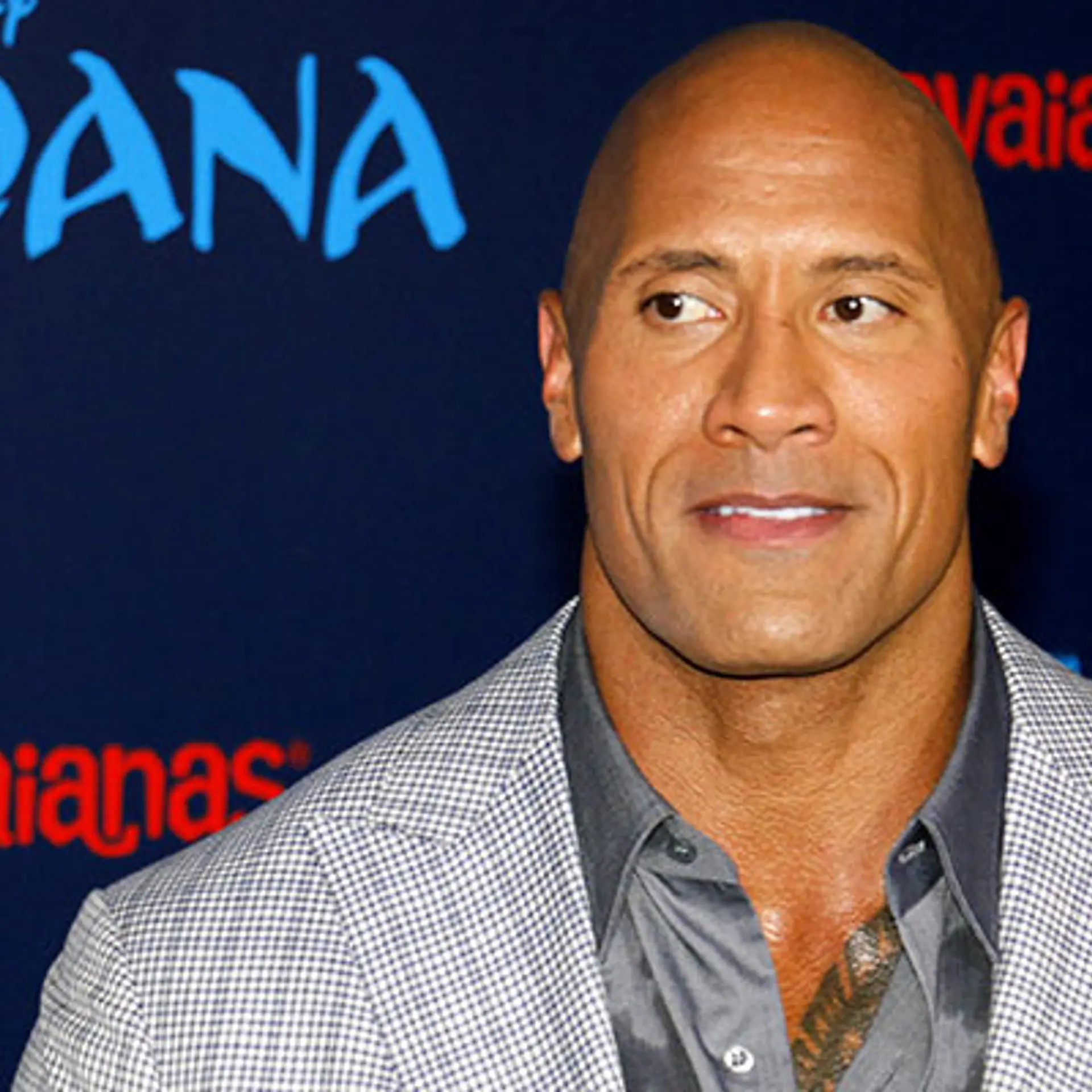

“Engineers and developers should remember who pays their salary. It is not their manager, CEO, or company; it’s their customers,” says Prashanth Susarla, 38, Co-founder and CTO of student accommodation platform Unilodgers.

With a career spanning over 16 years, Prashanth has been responsible for integrating the tech stacks of Citrus Pay and PayU India. He has helped PayU’s business grow by 5x and believes that growing for scale means getting one’s bearings and markers right.

The entrepreneur believes that only three things matter in the payments and API business: conversion rates, the speed at which you are paying out the funds you are authorised with by your customers, and how you deal with fraud and hacking while protecting the business.

“Scale these three problems and you don’t need to scale the hundreds of other features that you have built in every nook and cranny of the product,” Prashanth says.

Unilodgers was a part of YourStory’s Tech30 in 2018, a cohort of high-potential technology startups.

Prashanth Susarla, Co-founder and CTO of Unilodgers.

Goal-oriented upbringing

Hyderabad-born Prashanth spent the first three years of his life at his maternal grandparents' house, since both his parents were working. He grew up with two of his uncles, who were still in school back then.

“Since I was not inclined towards sports, books kept me occupied,” he recalls.

His elder uncle, who was then preparing for JEE, had math and physics books lying around in the house. “I liked gamification and whenever my uncle got those tutorial books, I would try my hands at solving them,” Prashanth says. “I could never make sense of those high-level math problems, but I would give them a shot.”

Prashanth also attended Vedic school in the evenings. His parents were quite passionate about the Vedas and even contemplated whether he should be trained to be a full-time priest. But his father, an MTech graduate, and his mother, a PhD scholar, decided otherwise.

“There was a certain discipline and rigour that chanting those extremely complicated Sanskrit phrases incorporated in me,” Prashanth says.

He says his upbringing was very “modern and contemporary”, and there was “not much hand-holding”.

Speaking about his “goal-oriented upbringing”, he says, “I was academically self-aligned and never needed too much help. That continues even today. When I am trying to learn something new at work, I learn it myself.”

Prashanth in Vedic School.

Architecture over programming

Prashanth never had a computer at home, but his mother enrolled him into a learning centre for programming in 1986. He was first introduced to the BASIC programming language, and would write codes similar to equations he was solving in math. For him, constructions like looping and conditionals came much later.

He says, “At the age of seven, I could differentiate between an IMB PC, a PC XT, and a PC AT. I was more interested in the specifications. More than the software aspects, the system side in computers attracted.”

In the next eight years, he had his bearings, with respect to computer architecture concepts, spot on.

Given his interest in numbers and science, it made sense to pursue engineering as the logical next step. He recalls, “I could sleepwalk through the math and physics classes.”

Prashanth wanted to study either mechanical engineering, like his father, or pursue electrical engineering, since he was inclined towards computer organisation. In fact, he was one the top 100 rank-holders in the JEE exams. His uncle advised him to take up computer science and engineering, since it had more opportunities and potential. Thus, Prashanth joined IIT-Kanpur to study computer science.

Prashanth got a personal computer in his second year at college, and jumped directly from BASIC to C programming language.

Mistakes are lessons learnt

Prashanth was a topper throughout his school life, but college was a whole new ball game.

He co-founded the Computer Club, Navya, in his third year. “I wanted to evangelise open source computing on campus and eradicate proprietary software, unlike what Microsoft was doing then,” he says.

Exposed to various programming languages, Prashanth tried his hand at different things. He believes that a lack of discipline and a bit of overconfidence that he didn’t really need to study, led to his downfall in college.

“I went down the rabbit hole of diving deep into computer architecture and open source,” he says.

Prashanth barely managed to scrape through college. His parents had to, as he says, counsel him through college.

Looking back, he says it was a lesson learnt early.

“You have to understand what makes you tick and makes you successful. If you change your routine in any one way, you have to understand what was complementing the earlier routine,” he says.

Prashanth could not change what had transpired, but in college he developed a deep liking for programming - building for open source, for the web, and for enterprise software. It was then that he first understood the concept of “using technology to solve people’s problems”.

Prashanth along with his batchmates during the convocation at IIT.

Given his grades, established companies “were not willing to touch me”, Prashanth recalls.

He joined Boston and Hyderabad-based OATSystems Software, which was founded by a couple of IIT-Madras and MIT alumni. The startup was then building RFID technology and working on how industries like retail, logistics, manufacturing and supply chain could function better using Radio-Frequency Identification.

Prashanth, who joined as a software engineer, would code in Java, writing the business logic sitting on top of RFID readers and hardware. He was the junior developer and was working on the in-memory database. “RFID was then considered the technology of the future,” he says.

Building for customers

After a year, Prashanth wanted to move out of Hyderabad. Abhishek Goyal, Founder of Tracxn and former associate with Accel Partners and his classmate from IIT-Kanpur, was working with a startup in Bengaluru. He agreed to put in a word of recommendation for Prashanth at Andale Information Technologies.

“This was one of the three career moves that Abhishek helped me make. It was a nearly 10-year-long chapter of influence that he played in my career, starting 2004,” Prashanth says.

Andale built SaaS tools to help eBay sellers automate their listings. Prashanth was assigned to work on the software development of Counters and Listers. Counters was the free product that would enable merchants to see how many times a particular page was visited.

“We did not have any framework like Redis then, to run or compute. Debugging of core processes had to be done by engineers,” Prashanth says.

He was the primary developer of the foundational tech for Counters, and wrote the distributed in-memory cache. He says since Andale was a customer-first company, engineers had to get on support calls.

Prasanth was the secondary developer for Listings, a paid product.

He says, “From the software developing prospective, it was like nirvana. Building the foundational technology, speaking to customers, and generating positivity among sellers was very satisfying.”

Back to base

In 2005, OATSystems moved out of Hyderabad and shifted to Bengaluru. Since Prashanth left the company on good terms, OATSystems got back to him, asking him to reconsider, and he ended up spending another three-and-half years with the company.

His second stint at OATSystems included him working as a developer, solutions engineer, and point man for external engagements.

Unlike earlier, he was now working on new product initiatives and plans in the roadmap. He wrote code for a version of the enterprise product that could run on embedded devices, including the RFID device.

Prashanth worked with clients, including Procter and Gamble, Airbus, and Japanese company Sumitomo Corporation. He wrote lakhs of lines of codes that had to work in Japanese, and closely worked with some of the clients’ factory and warehouse managers as well.

“My greatest learning was to build code that could work with any language in the world. While it was not technically challenging, it came with a sense of empowerment since I had to do it myself,” he says.

The tech team at OATSystems Software.

Working at OATSystems was very satisfying, but Prashanth wanted to learn more about product management.

“My mother kept pushing me to safeguard my future with a couple of extra qualifications,” he says.

Both his prior experiences were customer-facing. Since college, Prashanth had been interested in using technology to solve human problems, which is why he decided to shift from software engineering to product management.

In 2009, he got through to Indian School of Business (ISB).

“The goal was very clear. At the end of the ISB course, I wanted to work with either Google, Amazon, or Microsoft, as a product manager. These companies had mastered the art of grooming product managers,” Prashanth says.

A year later, in May 2010, Prashanth joined Microsoft Corporation as a product manager. This was in the middle of the development lifecycle for Windows 8.

As part of Windows 8, Microsoft was planning to launch an app store, and wanted to build a portal where developers could get data on how their apps were being used. Data would reveal things like how many times a particular app was crashing and the number of customers engaging with the app. “It was very similar to the stuff I was doing at Andale and it appealed to me,” Prashanth says.

However, the Windows app store did not take off as well as the iOS app store. Prashanth was also disappointed that he was not able to interact much with end customers.

“I eventually quit Microsoft because of the ‘big company dynamic’. It was more of a project manager’s job than a product manager’s,” he says.

Moreover, he had noticed that at Microsoft, it was a sub-two-year game. If an employee passed the two-year time frame, s/he had to stick around for a long time to the growth count. Prashanth asked himself if he could do a 10 to 15-year stint at Microsoft. The answer was clearly no.

“The two to three years’ of knowledge was very internal. There was no relevance outside Microsoft.”

Diving into the startup world

In December 2010, Prashanth once again touched base with Abhishek. He was with Accel and had, through the various pitches by entrepreneurs, realised that ecommerce was an exciting space. Abhishek went on to found Gurugram-based beauty and fashion ecommerce portal UrbanTouch.

After three months of procrastination, Prashanth joined UrbanTouch in August 2011, as the AVP of Products. “It was a good opportunity, and there was a lot of money to be made,” Prashanth says.

Prashanth, along with Engineering Head Qasim Zaidi, built the technology stack of UrbanTouch. He ended up spending more time on engineering than on product and, in 2013, was promoted as VP of Products and Engineering.

However, UrbanTouch was unable to raise a fresh round of funds. The team, unsure of when it would be able to turn unit economics positive, ran out of capital. The startup was acquired by Fashionandyou, but the company was soon shut down and Prashanth decided to leave.

Entering the payments space

Prashanth had shown interest in the payment segment while building UrbanTouch, which used PayU’s payment gateway. By then, Qasim had joined Paytm and his conversations with Prashanth mostly revolved around how exciting the payments segment was.

“I discussed this with Abhishek, but I wasn’t sure what to expect in the payments space,” he says.

Abhishek knew Nitin Gupta, Cofounder of PayU India, and put on a word for Prashanth.

“I was already in talks with a bunch of startups, including Walmart Labs and Taxi for Sure, but PayU had great set of product ideas in their roadmap and felt like a good opportunity,” he says.

Prashanth joined PayU in March 2013, as the SVP, Products and Engineering. At that time, PayU was comparatively new and had only one B2B product, PayU Biz. PayU Money was about to be launched then.

PayUBiz was built on PHP while PayU Money was built on Java; both teams were separate and reported to Prashanth.

“PayU Money had consumer ambitions. The plan was to not unify the tech stacks, but keep the two brands separate and later maybe spin them off as two different companies.”

At PayU off-site

In October 2015, Prashanth moved up the ladder to become the CTO of PayU. Recalling his experience, he says PayU was characterised by a brutal environment. The speed and intensity at which things had to be done, and the number of products it was trying to launch, while keeping interesting ones operational, were extremely ambitious.

He says, “We kept making mistakes and failed a lot of times. We did not get solving for scale very smoothly.”

Prashant believes that solving for scale is about getting one’s priorities right and going deep into a specific problem. At PayU, the focus always was to get the best possible conversion rates.

“When you start seeing the scale and the number of concurrent transactions pile up, you begin to keep your eye on the conversion rate marker and start optimising the code and architecture accordingly.”

Only when the conversion rate is up to the mark should a developer bother about the other bundled features.

Between 2013 and 2016, Prashanth and his team spent a lot of time on feature work and new products, and constantly kept losing track of the three big issues: conversion rate, quickly paying out funds that were authorised, and dealing with fraud and hacking.

The tech team was busy building the POS terminal and the digital credit card. However, one month before the launch, both products were killed. “It was diverting our focus from the core problems. What was required at that time was to get the engine right,” Prashanth says.

The team started having issues with scale. While fraud was still under control, conversion rates were going down, system up-time was decreasing, and the number of errors were increasing. PayU was slowly lagging the competition, RazorPay and JusPay.

Building for scale

Towards the end of 2016, Prashanth and his team got back on track; they cracked the problem by mid-2017.

Alongside, PayU acquired Citrus Pay in September 2016.

Prashanth says, “While solving for core problems in PayU, we also integrated for Citrus Pay. Today, the two tech stacks works as one.”

The biggest challenge, however, was deciding which stack elements to keep, since both PayU and Citrus Pay had individual payment gateways. Migrating to one platform, integrating customers of one with a new API, and stabilising the business would take at least a year.

He chose to unify the systems from the backend, building a new API gateway on top of the open source tech. Prashanth says he had to focus on the tech team and tech architecture aspects of both platforms, which had individual strengths and respective sets of customers.

“We ideally had to look to optimise, avoiding duplication, and use the best of every feature on both sides of the equation,” he says.

Prashanth built the features of Citrus Pay and PayU together, utilising the strengths of each pack and discarding the weaknesses. He also induced cross-pollination between the two teams, reinforcing that both the teams were working towards the same goal.

Growing the business

Under Prashanth’s leadership, PayU’s business grew by 5x.

He says, “For a business to grow 5x, you need a lot of understanding and cooperation across teams. It’s good to look at businesses that have grown by 5 or 10x. But if you look deep into their journeys from day one to day 100, they would have gone through lots of mistakes and learning.”

According to him, the secrets to success are cooperation and understanding within teams, having utmost clarity on problems that need to be solved, and tracking growth.

While companies can grow 5x by throwing marketing dollars, building new products or building new features on existing products, in reality, growing 5x smoothly is only possible by understanding what customers truly like about your product, what they are willing to pay for, and what they are willing to grow their business with you for, he feels.

Between March 2013 and September 2015, Prashanth was directly reporting to the CEO since there was no CTO. When he joined PayU, it was only a Rs 900 crore business. By the time he quit, PayU had reached the Rs 60,000 crore mark.

Taking the entrepreneurial plunge

Prashanth quit PayU in November 2018 to join Unilodgers, as the third co-founder and CTO. While the product had been developed, Unilodgers lacked in-house technology and Prashanth was tasked with building the tech pillar.

Since then, he has managed to build his own tech team and is now focused on scaling it. Going forward, given the space, he is experimenting with how payments can play a role in the students’ accommodation space.

Unilodgers falls under the long-term travel category with students booking accommodation for at least a few months. This requires heavy investment of between $800 and $10,000.

Prashanth feels students are underserved when it comes to interesting credit solutions. “Everything is based on students’ future earning potential rather than the present scenario. Some of them may not have the means to pay today. So, we are trying to figure out how to make than happen.”

Prashanth continues to code, but accepts that he is “not as fast” as the developers on his team. Looking back, he feels that his uncle, Abhishek and his wife had major roles to play in giving a definite shape to his career.

“What I am today is because of PayU. Everything else that I did was, in some form or the other, a stepping stone and learning that I could take away and apply later. PayU is where I learnt how to scale and solve problems with scale,” he says.

But he’s not done with learning yet. “I continue to be a student,” Prashanth says.

(Edited by Teja Lele Desai)

![[Techie Tuesday] How Prashanth Susarla helped PayU grow 5x after almost flunking out of IIT-Kanpur](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/3fb20ae02dc911e9af58c17e6cc3d915/techietuesday800x400-1577693737145.png?mode=crop&crop=faces&ar=2%3A1&format=auto&w=1920&q=75)

![[Techie Tuesday] PhonePe CTO Rahul Chari opted out of IIT to follow his heart and build a world-class product](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/3fb20ae02dc911e9af58c17e6cc3d915/RahulCharitechietuesday800x4001576480080084png?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)

![[Techie Tuesday] A reluctant engineer who went on to build tech products before their time - the story of Ramki Gaddipati of Zeta](https://images.yourstory.com/cs/2/3fb20ae0-2dc9-11e9-af58-c17e6cc3d915/Techie-tuesday-Ramki-Gaddipati-800x4001565613417336.png?fm=png&auto=format&h=100&w=100&crop=entropy&fit=crop)