Organisational resilience: how to build tenacity and innovation for the long run

This useful book provides frameworks and case studies for how companies can overcome traps of success and failure, and thrive even when strategy comes under challenge during crises.

Launched in 2012, YourStory's Book Review section features over 250 titles on creativity, innovation, entrepreneurship, and digital transformation. See also our related columns The Turning Point, Techie Tuesdays, and Storybites.

Frameworks for business longevity are explained in the insightful book by Liisa Välikangas, The Resilient Organisation: How Adaptive Cultures Thrive Even When Strategy Fails. The material is written in academic style and spread across 270 pages, with 18 pages of references.

Liisa Välikangas is the Professor of Innovation Management at the Aalto University School of Economics (formerly Helsinki School of Economics). She is also the co-founder of entrepreneurship-promotion organisation Innovation Democracy, and the Woodside Institute.

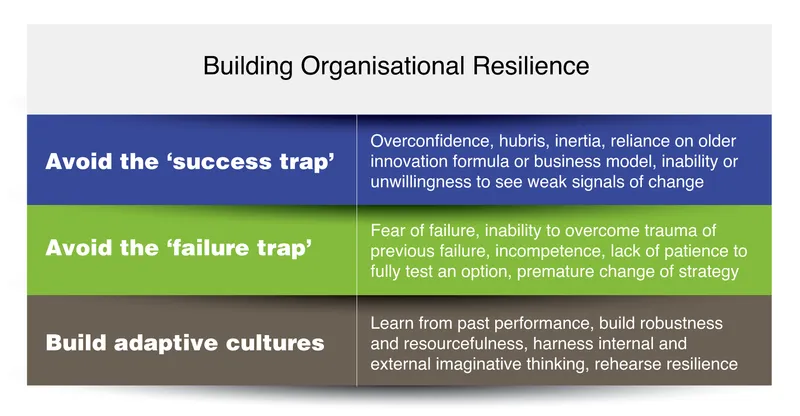

Here are my key takeaways from the book, summarised as well in Table 1 below. See also my reviews of the related books, Rebel Talent, Dual Transformation, Do Better with Less, Disciplined Dreaming, The Innovator’s Path, and The Other ‘F’ Word.

The case for resilience

Innovation and resilience are opposite sides of the coin of business longevity. Resilience has become the operative word for businesses in the aftermath of the dotcom bust and financial crises of the past few decades, and preparation for climate change. The book was written before the coronavirus crisis, but its lessons hold true today as well.

Resilience organisations are not prisoners of past success or failures. They have resilience baked into the genes of the organisation, and are not dependent only on leadership or strategy. They innovate even when they don't yet need to.

They don't just survive, they actually thrive in the face of challenges and unpredictable events. “The imperative of strategic resilience is to be right before it is too late,” Liisa begins. Resilient firms are able to harness change even before it becomes an opportunity or threat.

“Resilience provides the capacity to sustain strategy change,” she adds. It helps companies thrive even while it is pivoting to a new strategy. Unfortunately, many companies are stuck to routine behaviours and hierarchy, and are unable to invest in or benefit from exploration.

Liisa explains that resilience is more than recovery after crisis or persistence in the face of threat. Resilience is about changing before it becomes a forced necessity, without experiencing a crisis, and without accompanying trauma. It is about having the courage to see an opportunity where others see a threat, Liisa explains.

A truly resilient company does not see innovation as a distraction. It reflects and learns from past crises, and builds the ability to harness serendipity (“accidental sagacity”). Organisations can reduce the trauma of change via learning from others, small-scale experimentation, early prototyping, and virtual explorations or simulations, Liisa describes.

The author distinguishes between operational resilience (robustness, accident recovery or avoidance) and strategic resilience (capacity to change strategy and sustain it). Approaches involve a combination of engineering, talent, business models, and leadership.

Liisa lists a range of resilience tests, such as being able to overcome competition, attain broader social legitimacy, and the toughness of people’s character. External contributors to resilience include consumer insights and trust, and industry networks. Some cultures have tenacity built into them, such as Finland, thanks to factors like harsh weather and a history of surviving hostile neighbours.

Learning from the past

Success traps and failure traps are past legacies that can hinder resilience. Companies should guard against structural rigidity, lost capacity for experimentation, attentive complacency, lowered aspirations, and ‘tuned-out’ employees.

Liisa cites research on companies’ decline due to blinders of strategic frames, relationships becoming shackles, and values turning into a dogma. “Success is a great slave but a poor host,” she cautions. A combination of ambition and humility is called for (“humbition” in the words of Bell Labs researchers).

The author classifies three types of dangers of prior success: mental (inattention, complacency, arrogance, hubris), behavioural (less exploration, lack of diversity, excess scaling of prior models), and political (power coalitions, vested interests, lack of will to invest).

Other enemies of resilience are mediocrity, lack of imagination, and internal infighting. As ways to break out of such traps, the author advises running parallel experiments for longer periods of time to understand gestation effects, engaging with people with diverse worldviews, taking up social entrepreneurship, and practising sustainability under resource constraints.

As a case study of innovation trauma, Liisa draws on the failure of thin computing client Sun Ray at Sun Microsystems. “Learning from failure isn’t easy,” she cautions, observing that creative people can even become “innovation gun-shy” due to severe disappointment on the emotional and social front.

The trauma of failure can lead to cynicism, disillusionment, and demotivation, Liisa cautions. Post-mortem workshops, a period of disengagement, collaborative case-writing, and management of expectations can help in this regard.

Building adaptive cultures

“Strategic resilience is a capability to take serendipitous, opportune action,” Liisa explains. Leadership matters, but is not sufficient. “Resilience cannot be commanded,” she emphasises, “Resilience is what organisations can fall on when leadership fails.”

Leaders are sometimes susceptible to “commitment creep” (escalated support to untenable positions), cognitive myopia (learning traps, focus only on familiar areas), or a state of denial (inability or unwillingness to see change or problems).

Organisational resilience is built on innovation (high impact), design (robust, sustainable, dynamic), adaptability, and strength. Resilience helps deal with tough competition, reduced resources, ‘black swans’, or emerging disruptive technologies.

Liisa calls for “organisational ideativeness” as a resilience approach. “Idea exploration is an important strategy for the future,” she explains. “Ideativeness has little to do with brainstorming sessions. Rather, it is about the capacity to think of the future in different and sometimes radical ways.”

Thinking and talking about new scenarios helps builds resilience. The planning process is important, though plans may change. Multiple voices and diverse thoughts should be encouraged, even in conditions of scarce resources.

“Organisations are adaptive and fit when they rehearse change,” Liisa explains. Rehearsal should be a continuous and everyday activity, and should be everyone’s responsibility. All employees should be invited to rise to the challenge, thus helping build tenacity across the board.

'Framing contests' and ‘interpretational debates’ promote diverse thinking, and afford 'cultural insurance' against frontier change, Liisa writes. Teams should be able to perform under conditions of ambiguity.

Networks of independent people, the role of humour, and even “devil’s advocates” and “corporate jesters” help challenge basic assumptions. Extreme (best and worst) scenarios should also be contemplated. Such activities should be systematic as well as imaginative, and valuable lessons extracted.

Community and business reservoirs of resilience can be built via innovation networks (e.g. Silicon Valley) and corporate groups (South Korea’s chaebols). Operational robustness can be built through resource redundancy (e.g. spare/twin engines, mirroring, rotation).

“Constraints spark creativity,” the author explains. Resource-scarce innovation helps unearth opportunities for new products, eg. Haier’s washing machines with wider drain pipes for farmers to wash vegetables, or even make goat’s cheese.

Organisational design can also help robustness via modularity or structural components. Strategic robustness comes from factors that are cognitive (free of nostalgia, denial, arrogance), political (portfolio of experiments, allocation of resources), and ideological (moving beyond routine operations to renewal).

Though there may be resistance to or fear of change, it is important to embrace change for survival and to add an element of fun in the company, Liisa argues. Many companies have active “underground” communities focused on innovation and strategy. They are autonomous, grassroots, and creative, and help overcome “imagination deficit” in companies.

“Being resilient means taking turns even when the road forward still looks passable,” Liisa explains. It is like going to the gym, she jokes; it builds “change muscles”.

Local entrepreneurs can be supported via mentorship and investment; they help get around groupthink and top-down trickle-down theories. Imaginative and critical thinking, along with peer activities, need to be supported. Outliers help overcome limits of incrementalism, and test the frontiers of tolerance.

Corporate jesters, outside consultants, and even cartoons like Dilbert can act as defensive mechanisms against obsolete, dangerous and destructive ideas, Liisa observes. They remind leaders of the transience of power and fragility of success, but can themselves end up ridiculing those who question the status quo, the author cautions.

Based on the case study of a retailer transforming itself, Liisa recommends resilience-building activities like mapping impediments to resilience, a Management Innovation Jam (with ‘Jampions’), and creating an internal marketplace for ideas and talent.

Mentorship programmes, media artefacts and channels, and a portfolio approach to experiments also help. External activities can include involvement in community programmes for a larger cause, employee activism in CSR initiatives, and even launching spinoff companies.

Quick fixes and silver bullets are not solutions to long-term resilience, Liisa cautions. Companies should honestly identify “resilience deficiency symptoms” and unlearn outdated mental models. “What is needed is practising change rather than waiting until change becomes a necessity,” Liisa advocates.

Drawing on the case study of AT&T’s ODDsters (Opportunity Discovery Department), the author shows how a community of savvy engineers and managers raised the quality of dialogue about technology and strategy. They tried to move the company out of its tunnel vision and complacency, via tools like scenario planning and publication of research documents on emerging tech discontinuities.

The members had “willingness to ignore bureaucracy, the confidence to work without permission, and an unfailing capacity to deal with rejection,” Liisa describes. It included “heretics and activists,” who used creative imagery of “data bombs, freight trains, canaries and empty suits” to advance their cause.

Unfortunately, due to a combination of leadership opposition, executive changes and departure of talent, the group shut down. Some strategies may work well only in times of slow change, Liisa cautions. Change advocates should avoid confrontation and snobbery, and adopt systematic approaches.

Leaders, in turn, should actively engage and learn from those who have industry know-how, future visions, and unbiased opinions (sensemaking). They bring new energy and vibrancy into the organisation, Liisa observes.

Rehearsing a culture of resilience

The last part of the book addresses practices for rehearsing resilience approaches, presented in the form of ‘postcards’ case studies. But the momentum of the previous chapters seems to lose its way through diversions in this section.

The author advocates approach like open innovation, crowdsourcing, institutional activism, and nurturing networks of amateurs, hobbyists, and creative communities. Some companies like Google and 3M have allocated discretionary time to employees for innovative explorations, but few other companies have followed their lead.

Companies should harness their independent non-conformists and freethinkers. They act out of sheer passion and intrinsic motivation, rather than external rewards. Examples of such communities include the Homebrew Computer Club, which helped spawn Apple’s ideas in personal computing.

In a world of rigid bureaucracy and corporate specialisation, coalitions of creative rebels represent the spirit of innovation and freedom to experiment. They work across disciplines and industries, and embrace the convergences of technology, Liisa explains. “Resilient activism” helps in the long run, and should be supported.

Institutional entrepreneurship initiatives should encourage and support projects of such volunteers, and harness their playful energy to evolve an emergent strategy. This helps in agenda setting, scaling up cultural frames, and brokering to create deals.

From the world of politics, Liisa examines how the US Democratic campaigns have used Internet platforms for fundraising and connecting online communities to offline events. Local organisations and volunteers built on creative communication campaigns. Such principles of open organising and pervasive volunteer activity help build resilience.

Learning-by-trying helps “inventive experimentation” and “generative learning,” beyond “inferential learning” from other companies or research material. Rehearsing experimentation, hypothesis validation, and serendipitous connections push the limits of knowledge, Liisa explains.

The “hacker” attitude helps tackle important problems, and go beyond imitation. Other approaches to rehearsing resilience are skunkworks projects and expert contests.

The book ends with a brief discussion on resilient responses to challenges like political conflict (collaboration, mediation), unemployment (entrepreneurship), excessive consumerism (social responsibility), pandemics (global institutional governance), and social media domination (reformation).

“Resilience is something that needs to be rehearsed, not just planned for,” Liisa sums up. It should ultimately become “automatic, spontaneous, and reflexive.”

“Resilience will become something like an automatic process only when companies dedicate as much energy to laying the groundwork for perpetual renewal as they have to building the foundations for operational efficiency,” the author signs off, citing a paper co-authored with Gary Hamel.

Edited by Saheli Sen Gupta